PETER HADDOW

An Interview with Judith Rodriguez (mid-1993)

The Holden Barina pulls in to the side of Glenferrie Road. The left tail light is smashed and a smear of white paint stretches across the bumper. Judith Rodriguez gets out and walks quickly to her office at the Toorak campus of Deakin University. Hugged tightly to her chest she carries several books, folders, essays and large size envelopes.

At the door to her office she fumbles for the right key. Both her hands are gloved and she picks one key from the bunch and inserts it into the lock. She twists the key but the lock remains firm. She tries another key, then another, and another. ‘Fu…,’ she says, almost saying that word.

Inside her office she puts things down and then rushes out the door to her class, carrying another assortment of books, folders and large size envelopes.

At Fitzroy’s Perseverance Hotel her Saturday afternoon audience sit together in their groups of bohemians, university students, the working and the middle classes. There are people with ear rings, nose rings and two men have eye-brow rings. One couple have their hair dyed purple and someone else has her hair dyed an outback desert orange. One woman weas what looks like a chinchilla cat on her head and nearly everyone wears black or autumn colours. Judith Rodriguez, the featured guest poet, wears a red skivvy, tweed jacket and black slacks and waits near the stage listening to the other poets.

‘She needs voice training to project her voice,’ she says of one poet.

‘She’s not bad,’ she says of another, ‘but demonstrably mad!’

Told she is next to perform she excuses herself saying, ‘I must do the quintessential thing and go to the loo.’

On return she checks her bag and takes out a Casio calculator which incorporates a watch. ‘I’m always banging my wrist against something,’ she says.

Before going on stage the MC, Ken Smeaton, checks her biography details. She stops him in mid-sentence. ‘That’s quite enough. Don’t do any more.’

Smeaton’s introduction is naturally short, but effective. The audience whoops and claps as she takes to the microphone. She adjusts her glasses, and her lips move as she checks with the Casio. She puts it back in her jacket pocket. She is about to read from one of her many folders when she says, ‘No.’

Flicking through the pages she stops, then to the amusement of everyone says, ‘Yes!’

She turns slowly to face each section of the audience, her mouth twisting to the right as she reads ‘The Cold', ‘Tourists in the Pacific’ and ‘Tricycles for Geriatrics’ and others. Every poem at some stage in its reading gets a laugh from the audience. Expressionless, she shows no sign of being affected by their claps and cheers. Towards the end Rodriguez stops to check with the Casio, her twenty minutes are almost up. She reads one more poem from the folders then steps down to the table, her face flushed. Sitting down, she grabs at her throat and sticks out her tongue before picking up the glass of rum and coke she had been nursing for two hours.

Walking through the front door of her home is like walking into the State Library. There are thousands of books lining both sides of the corridor, from the floor to the high ceilings. At the back of the house where the corridor ends, is her study. The walls are decorated with her own lino cuts and framed prints. Several odd-sized tables extend like a pier from the back wall towards the door. Under the tables are boxes of papers and files. An old wardrobe holds lino cuts, frames and cassettes, and nearby there is a filing cabinet. With an oil heater on stand-by, she writes on an Apple Powerbook computer. She faces the back wall with the door closed behind her, and in good weather has the window open.

Books, literary magazines and violin cases are housed above the disused fire place, and some of the poetry she edits for Penguin is clipped onto the fireplace wall. She makes coffee, ‘I’m addicted I think. I drink far too much.’

She relates of going out to dinner with her second husband, the writer Tom Shapcott. While waiting to be served she began to write a poem which she had been carrying in her head for two years. Ignoring her husband she wrote twenty lines by the time the main course had arrived. They didn’t speak except when it was time to leave and the poem had been finished on a sandwich plate. Rubbing her hands together she says, ‘He doesn’t get upset at writers.’

Judith Rodriguez is a lecturer in professional writing and literature, and for Penguin a poetry editor. She was born in Perth in 1936 but grew up in Queensland where she began her university studies. As Judith Green, she was first published at the age of twenty-three. In her youth she played violin in university orchestras and was a member of an ensemble. She reads four languages and has lived and travelled extensively around the world. She has been married twice and has four children to her first husband.

Her literary output includes contributions to more than eighty Australian publications, and more than twenty from overseas. She has published nine collections of poetry, a play, designed book covers, translated a short novel and poetry, edited, reviewed, and has written the libretto for the opera ‘Lindy’.

Judith Rodriguez has won various awards for poetry and in 1978 won the South Australian Government ‘Prize for Literature’. On three occasions she has been granted a Senior Fellowship by the Literature Board of the Australia Council.

Interview and photograph by Peter Haddow.

HADDOW: At what age did you say to yourself, ‘I’m going to be a writer?’

RODRIGUEZ: I did start writing rhymes as a little girl … my mother would have encouraged me at five or six. At eight I was writing little poems. When I was in secondary school, I had poems in school magazines. I think I had thought of myself already as a writer – teachers of English tend to suggest it. I got serious about poetry when at the end of my teenage years I fell in love. Being miserable always fixes such a passion for writing … though in a first interview with The Age, in the early ’70s, somehow I was ashamed into shyness by Stuart Sayers and said, ‘I’m just a house wife.’ But I don’t think I thought of myself that way.

Some of my research suggests that you believed you had a tendency to defer to men….

Well, yes, I mean....

As if your role was one of just a house wife, that it was your role in life….

Nobody in my family would ever have thought of me as housewifely or deferential. I’ve never felt like deferring to other people’s opinions without examination.

I had the impression that perhaps you felt you weren’t quite up to the standard of men.

It must have been irony. I try to catch myself up quickly if I conspire at second-lining myself. One of those moments was when I was hitch hiking with David Malouf round Europe, and I said in some januty sort of way that I could write his biography, and he said yes, I could write his biography. Later on I got quite mad at myself for that. The eager subordinate.

How do you go about writing? Do you use the pen, a typewriter….

I like the act of writing. I think most people who can bear to look at their writing, do. Recently I’ve gone straight to the keyboard when I have some lines in my head. Writing’s more pliable, more thoughtful when it’s still in that stage – you want physically to have more contact with it. But I don’t think the keyboard is preventative like authors pretend it is.

Note pads?

I take note pads with me all the time and it’s a very good way of guaranteering you won’t put anything down. I write a lot of things down on my wrist, my children taught me to do this. A dirty habit, but a useful habit.

When you were a university student in Queensland, you showed John Manifold some of your best poems and he was fairly critical, saying that they were emotional and low on skill. A few years later you were published alongside Rodney Hall, David Malouf and Donald Maynard in the collection ‘Four Poets’. How did you feel about the early criticism of your poetry?

I don’t find criticism puts me off, I find that a challenge as far as I am concerned. I can never believe in the people who say, ‘Oh somebody will tell me that something is wrong here and then I will have to give up writing.’ They just don’t want to write.

How did you find the transition - from being single, with no responsibilities other than to yourself, to being married and having children – affect your writing?

Of course you know it’s all mad … I believe Judith Wright’s poem ‘Naked Girl and Mirror’, where the young girl seeing herself becoming nubile says farewell to her real self and adds, ‘We’ll meet again.’ That’s exactly how I feel. I am a single girl inside.

I think marriage is one of the sillier institutions. I keep on feeling that I should be giving more to the relationship or I should be giving more to my children, which is all pretty ridiculous as my children are all over twenty-one. And the marriage relationship you can mould to your own version. But it inconveniences me because I like living alone and I find that again and again. Whenever I find myself travelling and staying at a hotel … I adore it. It suits me, you can get on with your own life. With a family you can’t.

So how did you do your writing once you were married and had children?

I did it over a heating duct in the kitchen which gave me asthma. I did it having very hot baths or very late at night, which I still do. This is in Melbourne. I get off the ground rather slowly in the morning and start to hum about nine in the evening…. I used to but don’t now cook, however it has made my children excellent cooks.

How late do you work to?

Sometimes to three or four in the morning. That’s stupid but it happens. It’s just that everybody has gone away. Unfortunately, two of my children have formed late night habits and they may still be around! I keep trying to find this little time-hole where you can have nobody at the door, no requests and even no news, and it’s very hard to find.

To work at your best you need solitude?

Well, I need sociability at some times nd solitude at other times, which is why I teach and why I write.

You need time to absorb and then retreat….

And energy. Especially with younger people, students. I find that is just so rewarding. And one to one talks are best; a roomful of people doesn’t do much for me. You can’t say something, you can’t learn anything…. Same with dinners. I love seeing two people or even four, but more than that seems senseless.

How did the demands of writing late into the night conflict with the demands of children who perhaps wanted to get up two hours after you’ve gone to bed?

Well, I suppose I’ve managed to get up whenever I’ve needed to. I think it’s made everything less good … my teaching … my writing. Everything slows down. I’m probably mad not to chuck the teaching and just go and write if I have it in me.

The whole thing about being a woman is the hidden knocks and draining. The women I respect, the women who I feel have sense, have engineered themselves into the situation where they don’t owe a lot of services to a lot of people and they can get on with it. There are traps around you and you can advise other people about them, but it is very hard to avoid them for yourself.

Have you always worked?

There was no such thing as maternity leave. I knocked off teaching in London four days before I had my son, and my daughters were all born during semester breaks. I would advise any woman against having so little time off, but it worked, it worked.

My mother once said she’d thought I was going to be an artist, and I said, ‘You always made it perfectly clear to me I had to get a salary.’ That’s very deeply ingrained in me if I’m not actually earning, I feel completely worthless. Which is not the right way for a writer, certainly not for a freelance, because the pressure becomes terrible.

How did you manage with child care and things like that?

In England I felt we couldn’t afford it. Until my third child was born I’d batten upon a woman whose child seemed to like my children … finally I realised I couldn’t honestly do my university work unless my children got full day-time care. And that’s what happened. My youngest child got looked after from three weeks.

Women writers who have children, a family, seem to have a difficult time just finding the time to write.

People keep their hands off a man’s time … in the end you have to make your own conditions. And look at household groupings! My parents wanted me to stay at home until I married which was ridic … I departed. Those days are not today, but kicking kids out is not so easily done in a recession.

I do admire the writers Michael Holroyd and Margaret Drabble, who are married and live separately. And I gather Don Watson and Hilary McPhee ran their marriage thus. It all makes sense to me.

In the end it becomes a question whether at my age you have the concentration to do things. Well, I proved to myself that I did. I wrote the bloody opera.

How long did it take you to write ‘Lindy’?

Well, we went up to Uluru in August 1991. I’d already written a bit of a scene. That was no good, I threw it out. Then somewhere round Christmas I got started and I had it all hanging on the shelves and cubboards there (indicating) – fourteen scenes, five there, five there, four there. I was aiming to get a scene written a week, and that was over optimistic, other things going on. Then the semester started! I got the last line down in May, so you could say it took four and a half months.

How did you become involved in the opera?

I think Moya Henderson asked Gwen Harwood first, but she declined, and there might have been another person. Then she asked me, and I was very enthusiastic about it. One, I liked Moya and two, I thought broadly as she did about the Chamberlain affair, although we had different routes into what we meant by it.

With Moya Henderson living in New South Wales and you in Victoria, how were you able to collaborate with one another?

The bills for fax and phone and postage show how we did it! I went up to Sydney last month, and she was down here recently.

What’s the process though? Do you give her the words and she then works on the music? What do you do?

We discussed it first – then the process you’ve described. It doesn’t finish there. Moya finds that as she writes music she needs to have some extra words. She’s done her own words for some earlier works, often fairly chatty or colloquial texts, and she’s very inventive. There’s sometimes a problem about that, I do have a sense of ownership, and I find it just as embarrassing to own to the excellences as to the less successful features that aren’t mine.

How are you working at the problem then?

At present we’re going back to the basics – point of view, proportions … back to me writing text and her making suggestions. Then … at the stage where she writes the music, the words themselves are set, really. I can see a great advantage to a musician writing the libretto or at least having a decisive hand in it. But as long as I’m writing it, if something is absolutely not me, then I have to say so. I’ve steered clear of collectives where it was assumed individual skills would not have free rein. It’s really very testing. There’s always the possibility the sharing the attribution of the libretto.

Is there a specific theme to ‘Lindy’>

Apart from the struggle for justice, I think it’s the discovery of Myth right in among the daily news. In myth you find patterns of events that define human beings and groups to themselves – often through the most tragic and horrible things that human beings can do to one another. What starts as a suspicion, rather than a clue or a case, becomes an international event, an execution – the escalation’s hard to evoke in an opera with limited forces. The devastating effect it had on the Chamberlains is quite clear.

In many ways they were more a victim than their child Azaria.

That is true isn’t it. Anybody who tenaciously fights to win when the other side has already ‘won’ is going to suffer a great deal. But some kinds of character don’t take to cutting their losses. Certainly Lindy Chamberlain after her release was one of these.

In your research did you meet either of the Chamberlains?

No, but Michael Chamberlain and Moya have met, at a concert in fact.

It’s been said to me that you like the bizarre and the extreme.

No, I think the only bizarre or extreme thing I have done is marry a Colombian. That would be my parents’ view of it.

You spent some time in Colombia with your first husband. How did you feel going there from your own country to his?

I enjoyed it tremendously, even though we didn’t travel about as much as we’d said we would. And I don’t want to go back except with somebody who is native to the country. To go there and be treated as a gringo would be dreadful. Once I had an orange thrown at me in the street. It hit me in the face and Fabio didn’t protest and he didn’t bother with how I felt, he said, ‘Walk faster!’ Which was the right thing. I know why people there feel like that.

You grew up in Queensland and have spent the rest of your life living everywhere else in the world but Queensland. Why haven’t you gone back?

I landed a job here. Then there were problems, from seeing Queensland from outside. When I’ve come back, for instance, I’ve found Brisbane people who went to school with me had absolutely no notion of a proper parliamentary system – let John Bjelke-Petersen appoint a judge to a court where he had a case, fine!That was distressing. Of course, the Fitzgerald enquiry made a difference.

Do you have any role models?

Queen Elizabeth the First wasn’t bad was she? Musician, poet and so on, and who wouldn’t like a little power? I find it very hard to single out models because there’s something temperamental about me that wants to be able to think about many…. Devotion to one set ideal and following it and battening on it, I’ve never felt like that about anybody.

What about writers, are there any you admire?

In Australia I admire Thea Astley whose output has been terrific and has always gone further every time … ‘Beach Masters’ is a beaut short novel and there are just so few Australian novels about the Pacific. When she gets called upon to talk in public or for an interview, the way she snarls and crawls out of it is peculiarly Australian. I love her, she’s marvellous. Everything except her chain smoking, it’ll kill her in the end.

Is it important for Australian writers to maintain an Australian identity in their work?

Yes, I think so, and continue to create one. Anyway, how can we help it? If we write out of the effort to understand and be where we are and what we are. Our arts are already so various, and there are so many people involved in them they can hardly stop at expressing any simple program, bushloric or French learned, native or foreign. It’d be nice if readers could stop trying to sum up with One Program and a Supremo, One Supremo, from each generation in each art – then they can enjoy the variety, a three-dimensional identity, so to speak.

How did you get interested in the character Nosey Alf, from Joseph Furphy’s ‘Such Is Life’?

‘Such Is Lie’ is one of my hobby-horses, it is such n extraordinary book. I was always convinced that every one of its characters had a model or several models among people that Furphy knew quite well, and that Nosey Alf would be known around the back-blocks. One day in 1974 I was in the State Library and I was reading old numbers of The Age, orThe Argus, and in an 1893 newspaper I found this one and a half inch item which noted the death of a labourer at Elmore, and that the certifying doctor had found it was a woman. I spent the next three and a half months researching this and in the end made contact with a police sergeant who had been researching his family history and looking for the same facts.

What interested you though in Nosey Alf, the character?

The actual woman had her face knocked about by a horse’s hoof when she was sixteen. This really was fatal to her chances of leading a normal life. She was just a rather solid farm-girl. The conjecture that she was a lesbian, the notion that being kicked by the horse had driven her a bit dotty … I found the divergence interesting and the actual woman’s flight from her family and the things expected of her. Normally she’d have married into the kitchen of some farmer’s house.

So was it the woman doing the unexpected that attracted you to the story?

Yes. I think so and the fact that she had been fully constructed by a man, Furphy, for his own purposes. He very much desired to find an accomplished and talented woman, but one who was hidden and very much unavailable – and he constructed her, in Nosey Alf … the reality was very much sadder and more ordinary, but in its way very, very strange.

Why did you go to Robyn Archer and collaborate with her to write ‘Poor Johanna’, which was about Nosey Alf?

She set a poem of mine in 1976, ‘The Questioner in Black’, to music and I met her at a festival where she played it. From then on we kept in touch and worked on three ideas of mine, and she fired up about Nosey Alf. She said it would make a wonderful play. I would really like to write a novella about it.

Do you intend to write a novel or novella?

Yes I do.

You seem to collaborate a lot with other women.

I think I understand women better.

Are men hard to understand?

Not to understand, but they can be hard to work with I think.

How are they hard to work with?

I suppose a different way of regarding commitments. I understand that Moya talks about work and the other things she does. I don’t feel my timetable and priorities exist when I speak with some men. Again, it strikes me that I’m in a false position not only with them but with my two women collaborators, in that they do their writing and music full-time, I teach. It’s not off the subject, but it swallows time.

You seem to have an attraction for the colour red.

My mother foisted upon me in childhood a devotion to green, the ‘Don’t get too angry, don’t get too passive’ colour. My maiden name was Green. I’m glad Green means positive and fighting things today. But anyway, when I’m feeling bland I think back to decorator greens and when I’m being myself I wear red.

I notice you wear red nearly all the time.

A bit of red – yes, even when it clashes. My bit of rebellion.

You married Tom Shapcott in 1982 and have kept the surname from your first marriage. You’ve been published as Judith Green and Judith Rodriguez. Have you ever regretted losing your maiden name Green, at least on a professional basis?

I think of myself as Judith Rodriguez. I mean that was one of the most basic choices I ever made in my life. Both times I married I felt as I approached the fatal words, that I was doing the wrong thing … certainly my parents thought of Fabio as a coloured man and wouldn’t have liked it, and I was pregnant … it was a big decision to make. Much bigger than the one with Tom.

A lot of women today keep their maiden name.

I probably would if I married today. It’s very interesting how fashions come and go. Dorothy Hewett, Judith Wright, Rosemary Dobson – use their own names. Fay Zwicky, and a lot of women from my generation, kept the name that they married first. You can’t keep changing. And I like the name Rodriguez.

David Malouf seems to have had a big influence in your life.

He’s been a friend of mine since I was thirteen. I suppose we have influenced one another. He educated me a lot in Europe. We’ve known each other a very long time, that’s all.

How do husbands react to you having friendships with other men, like David?

Fabio had difficulty in accepting that I was going to Sydney to visit David. Coming from Colombia, it was a difficult idea. Too bad. You have to be free to enjoy friendships, one to one or with the kids. It’s just crazy to conduct them across domestic situations, under constraint because there’s one ‘not-exactly-friends’ corner. You should be free to be what you are, and that is that person’s friend.

So you went to Sydney?

I did. I find old friendships are very important. I regard husbands as very good friends, too. Marriage does tend to cut people off from other relationships – it should be good even for loners! To some extent, I am a loner.

A lot of writers are….

I think it’s a necessary condition. I mean, you’re not lonely, you like to have conditions where you actually can think about things you want to think about. Instead of being muddled around by the idiotic bits and pieces of toast on the floor or whatever.

What would you consider to be a good poem?

A good poem pulls at your heart and it strikes you as a precious thing.

How do you know if a poem is good or bad?

I suppose it goes on being a precious thing. If a poem goes on being a good poem then it goes on being something that you cannot do without. It clings to the memory. I don’t know of any other criteria other than memory and of the wish that you can’t do without it.

Which of your own work is a favourite?

I suppose the ones that sill have a development point in them. ‘Eskimo Occasion’ always astonished and pleased my family, and also pleases people as a reading piece … ‘Witch Heart’ which is about Robyn Archer performing, that pleased me … ‘Legends of the Novado’ which is about the volcano we lived near in Colombia … and ‘The Cold’ which is about Barbara Giles.

What’s your state of mind when you write poetry?

Usually it’s apprehensive and expectant. And at the same time, perfectly quiet. Other things do not matter which is a very nice state of mind … as far as I’m concerned it is exactly similar to the kind of high you get when you’re pregnant.

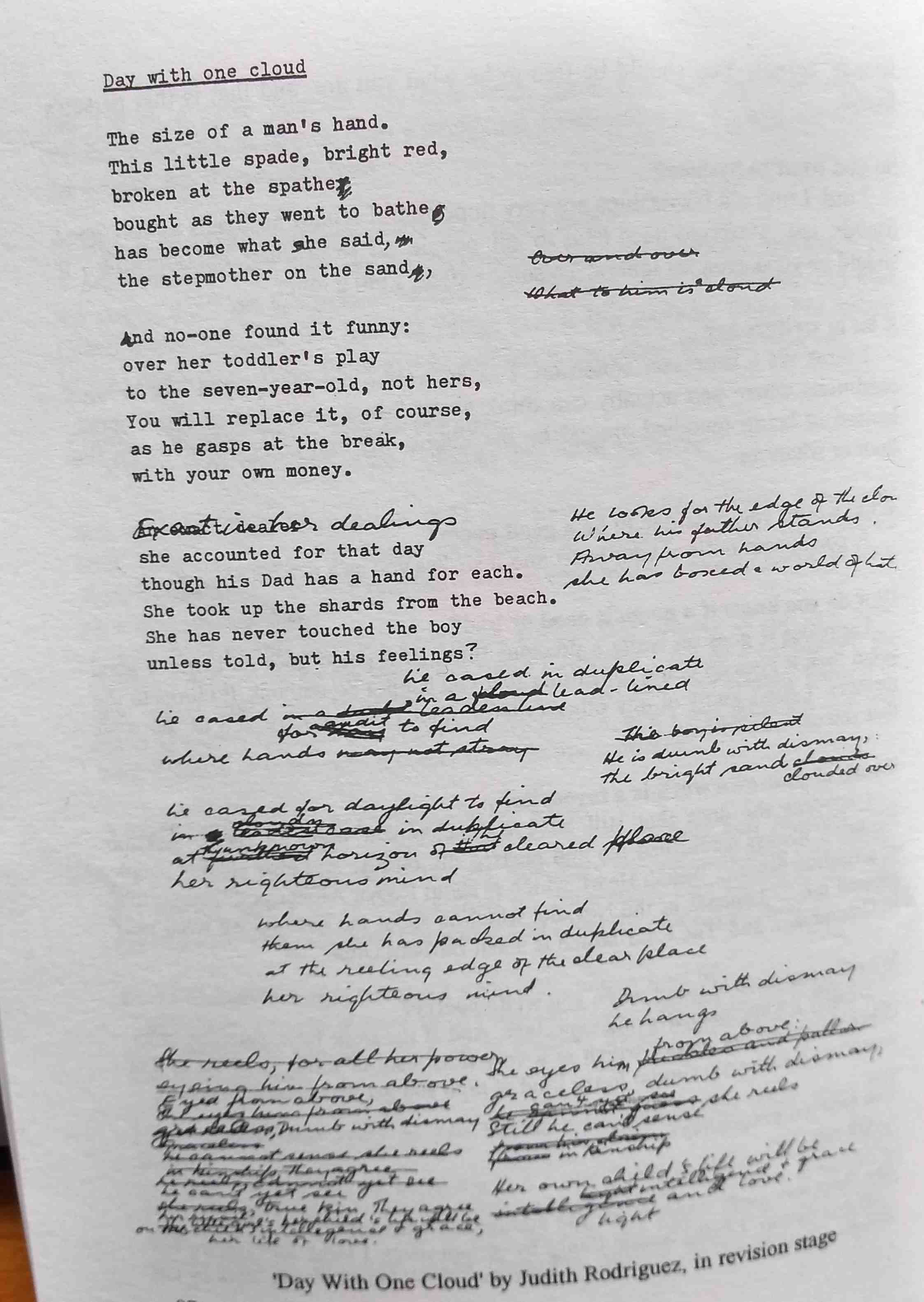

'Day With One Cloud' by Judith Rodriguez, in revision stage

You enjoyed pregnancy?

Oh yes.

Are there any poets whose work you admire over any others?

(Long pause) I enjoy certain things by certain poets. I think for instance Fay Zwicky’s ‘Ark Voices’ is a marvellous creation. I think lots of the big work by Les Murray is marvellous. I really do enjoy Ken Bolton and John Jenkins in tandem, they’re amazing. Their first one was called ‘Airborne Dogs’ and that’s exactly how they sound, a pair of young dogs and they really enjoy it. Barry Hill’s stuff is terrific … Caroline Caddy … I’m not even going overseas or to earlier poets.

What about Jennifer Rankin; you edited a collection of her poetry?

I didn’t know her. I did see her – a very beautiful and high-strung woman. And ambitious. When she died, of cancer, I think she felt that she hadn’t quite made enough way in her caeer … I think living with Frank Moorhouse and then with David Rankin was difficult. Maybe a challenge. But she didn’t like being cast in the shadow. She has a special quality – many of her poems are a meditation on place, some have a particularly strong vocation of childhood, and places she’s lived. And nobody does it quite like her.

Is poetry the most direct contact with dreams and the subconscious?

I can never remember my dreams. Or so few, I’ve written a couple as poems. I think what you’re saying … there is a relationship. And the freedom poetry has to move between a very deep and a very shallow level, holds surprises for you as you write a poem.

How do you feel about literary grants?

They were a wonderful help to me, though I wish I’d made even more use of them. I did produce three to four times as much as I would in other years. You can follow up your ideas – my books got finished as a result of time on grants. There’s a real problem about accepting a grant for a person on a salary – and probably with a family to keep. Vin Buckley got blamed for taking up a grant which probably halved his year’s income, so that he could write full-time.

You’ve had a life, ‘full of excitement’ including two marriages and the loss of a breast to cancer. Writers are generally thought to be manic depressive, even suicidal. One source told me you said cancer wasn’t going to make any difference to your life.

(Laughing) It could have made quite a difference to my life! I was marking an essay the other day and the student who wrote it was equating manic depression with creativity. I thought, ‘Oh well, I’ve failed again!’ Of course I can get quite frenetic, probably caffeine … I have had some low periods in my life, and when I look back they are the things I want to write about. I mean there is the year I call the Long White Year, because I spent it in New Zealand at the wrong age. And other times. If by the time you’re fifty-seven you haven’t worked out a way to live with yourself, you’re a very unhappy person, and I don’t think I’m that bad.

People who survived a tragedy, a near death experience, have generally said that it gives them a greater appreciation for life, they go out and grab it much more fiercely….

I left my first husband in 1980 and a lot of cancer cases are connected with great stress. I went on doing the things I did because basically I had to do them. I don’t think the cancer made me a very different person, I don’t know why. I’ve always felt that one was battling away, and this seems to be what one goes on doing.

You have a lot of commitments. Where do you find the time to write?

I don’t find very much! If it looks like spare time, then I know I’ve forgotten something. But I feel I have still something to give as a teacher – and the Penguin poetry editing I love, because we’re doing something diferent with the list. I’m trying to cut back on involvements in writing societies.

I remember you saying that you strive on stress….

There is a limit to that. You can’t, and you shouldn’t.

Poetry collections

'A question of ignorance' in Four Poets (1962)

Nu-Plastik Fanfare Red (1973)

Water Life (1976)

Shadow on glass (1978)

Mudcrab at Gambaro's (1980)

Witch heart (1982)

Floridian Poems (1986)

The House by Water: New and Selected Poems (1988)

The Cold (1992)

Play

Poor Johanna (co-written with Robyn Archer) 1991

Libretto

Lindy - for production by the Australian Opera in 1994

PETER HADDOW was a founding editor of Brave New Word and has contributed to various newspapers and magazines. A former police officer he has also been an adviser for film and television, including Blue Heelers, Halifax and Water Rats.