Ralph Wessman | North to Garradunga

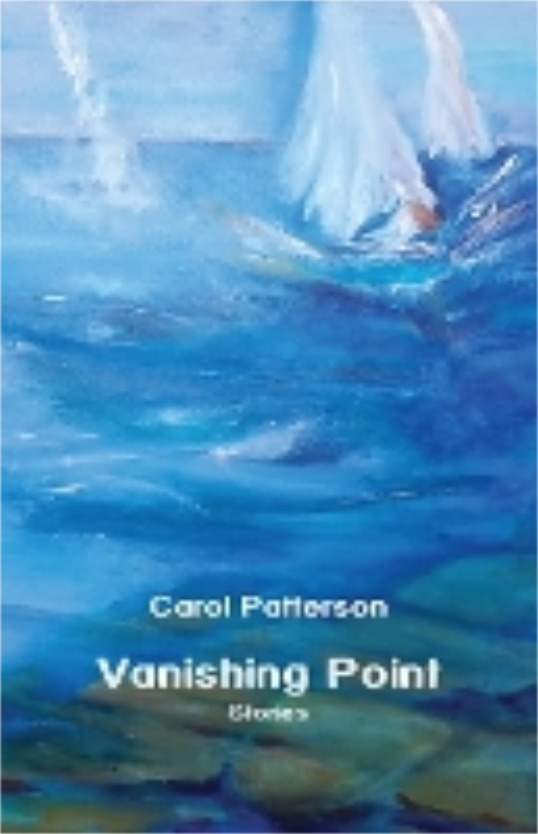

Launch: Carol Patterson's

short story collection, Vanishing Point

Quixotic Books, Launceston, 10th April at 5.30pm.

Robyn Friend will be swinging the champagne bottle...

Carol Patterson, a Tasmanian writer, has been crafting compelling short stories since the 1970s, though it wasn’t until 1980 that they first appeared in print: ‘Killing the Drake’ (Hecate, 1980), and ‘The Dress’ (The Tasmanian Review, 1980). Carol's writing since then has graced the pages of Island, Hecate, The Mercury, Preludes and Picador New Writing on many an occasion, and been published in three short story collections. One of her stories – ‘Tabula Rosa’ – appeared in Famous Reporter # 6 in 1992, probably where I first became familiar with her work.

In 2000, Carol teamed with Edith Speers to edit ‘A Writer’s Tasmania’, (published by Speers' acclaimed

Esperance Press, 'The World's

Southernmost Publisher'), commended as ‘a guidebook to the soul of a

remote and beautiful island written by fifteen of our finest writers' (a line that may have planted a seed in the mind of

Pete Hay

for the title of his prize-winning essay collection published some two decades later,

‘Forgotten Corners:

Essays in Search of an Island’s Soul’).

In 2000, Carol teamed with Edith Speers to edit ‘A Writer’s Tasmania’, (published by Speers' acclaimed

Esperance Press, 'The World's

Southernmost Publisher'), commended as ‘a guidebook to the soul of a

remote and beautiful island written by fifteen of our finest writers' (a line that may have planted a seed in the mind of

Pete Hay

for the title of his prize-winning essay collection published some two decades later,

‘Forgotten Corners:

Essays in Search of an Island’s Soul’).

The Patterson / Speers collection featured fifteen Tasmanian writers describing their experiences of various localities

throughout the state. Besides Amanda Lohrey’s Foreword, (which addressed the writer’s power, and privilege, in being

able to ‘express in words the love of place that most men and women feel with a passion second only to their love of

family’), other essays appeared from Vivien Smith, Alison Alexander, Robyn Friend, Barney Roberts, Carol Patterson,

Geoff Dean, Richard Davey, David Owen, David Young, Bob Brown, Tim Thorne, Elizabeth Dean, Margaret Scott and Tony Rayner.

Tim Thorne’s contribution spoke of his

enduring relationship with Launceston, the city he called home. ‘Where I live and write is

about halfway between Mount Pleasant and the Gorge, between the Gothic gloom of the old colony and the grandeur of

unrecorded history and pre-history. Even without the proximity of these physical reminders it is difficult to imagine

being a writer in Launceston and not being affected by both sets of forces.’

Geoff Dean's contribution described the experience of living in Tassie as a writer. ‘How do I fit in? Quite comfortably

I reckon. When I come back from a couple of weeks holiday the post office staff and the local shop keepers tell me all

the news that’s happened while I’ve been away. It’s a kind of emotional tender-trap, this constant adventure of mixing

with the eccentricities of country dwellers. It is what has held me here in Tasmania generally and in the Huon

particulalry when my intellect was telling me all the while that the way to literary success was to do what

several of my writer friends and acquaintances had done—to move closer to the literary action, either in

Sydney or Melbourne. You’ll never make it in Tassie, I was told, it’s a backwater and nobody really cares

aobut writers down there. Was I wrong not to leave—to take my chance with success? Well, hell, it depends

on the meaning of success I suppose.’

It was a refrain repeated throughout his career; that, and of a corresponding

need for a local publishing house:

For years, you’ve been a proponent of the establishment of a

Tasmanian publishing venture akin to the Fremantle

Arts Centre Press …

Yes. Because of its isolation, I think Tasmania needs a local publishing house … the strait is not much different from

a desert in many ways, it’s equally as isolating. The thing that would have helped me most throughout my career would

have been a local publishing outlet through which I might have had my books and stories published possibly ten years

earlier. (Support he was to successfully find, as it happens — both from Speers' Esperance Press, known for its commitment to

showcasing Tasmanian voices,

and from Roaring Forties Press, a Tasmanian publisher

established by Anne Kellas and Giles Hugo).

Margaret Scott’s essay presented a post-1996 Port Arthur appraisal of life on the Tasman Peninsula, a place which,

she wrote, ‘doesn’t feel like living in a peaceful backwater. Since april 1996, when Port Arthur became the site

of the worst peace-time massacre by a lone gunman anywhere in the world, we can no longer see our home as a haven,

affording escape from the violence of the cities. Even before that, it was clear that a writer had no need to leave

this community to understand much more than a single place or a single group of individuals. If you look closely you

can read a wider, deeper story which supplies a bottomless well of material and stands as an image of what can be

implied in the particular. You have only to look at the landscape—middens left behind by the Pydareme, the forests

which have grown up behind the axe-men of a hundred years ago, the farms swallowed up by the bush, the paddocks that

were once orchards, the new communes and caravan parks, the young people crowding on the bus to town, the old

shuffling across the road to the post office.’

Patterson’s own contribution to the collection recalled a trek along Tasmania’s Overland Track: ‘Walking

the Overland Track – Walking the Narrative.’

Two Europeans came along the track. They were elderly and wore expensive gear and they had those walking sticks

that Europeans use, poking out at angles. They were making heavy weather of it, no doubt conned into thinking

the Overland Track was a gentle doddle by the tourist pamphlets that Tourism puts out.

‘Does it get any worse?’ the woman asked.

All of us thought of Frog Flats behind us.

‘Oh no,’ we lied brazenly. ‘Duckboarding from now on.’ What was the point of telling them the truth, poor things?

There's a delightful tale Canadian writer Laurie Brinklow tells of when she

first met Tasmanian Pete Hay (who doesn't feature in this book, by the way) in Prince Edward Island in June 1998. Laurie and Pete were taking part in

a “Viking Hunt” with Icelandic saga scholar Gisli Sigurdsson, on a small boat off Canada's east coast,

(Gisli's research suggests a link between Prince Edward Island and 'the fabled “Vinland.”')

'Pete was the only person on the boat whom I didn’t know,' Laurie recalled, 'so I plunked myself down beside him and said hello.

When he responded with a cheery “G’day,” I said, “You’re not from around here, are you?”' Their ensuing conversation was catalyst

for a significant turning point in Brinklow's life, the decision to

follow her dream and 'explore my passion for islands by undertaking a three-year PhD

program at the University of Tasmania, looking at culture on the islands of Tasmania and Newfoundland'.

Robyn Friend's not from around here either. She was at one stage of her life living in Melbourne 'with a good job, two kids, an unemployed—and therefore suffering—post doctoral husband and facing two choices: to stay in Melbourne and lose my marriage or give up my job and follow my husband

to one of two offered places, a remote research station in the high country of the south island of New Zealand or Launceston. I

opted for Launceston. And found myself in this brooding pretty prison.'

Robyn's inclusion in the anthology

represents the only instance where two writers — Friend and Thorne — engage with the same location; Launceston, in this instance.

But her impressions differ markedly from those of Tim Thorne — or indeed, from all other

contributors to the book, who remain completely invested in the state. Not Robyn.

Her essay recalls discussion with an acquaintance of 'the pleasures of living in this charming regional city, the leisurely pace

of life, freedom from traffic jams, the relatively low cost of housing, a proliferation of reasonable restaurants, few

but affordable cultural activities, theatre in the Gorge, the film society, the improved quality of the book shops. Suddenly she

[her acquantance] burst into tears. Between bone-shaking sobs she managed to say, "I feel imprisoned here. I just want to go home, but I don't

know where that is any more. I've been here too long."'

Robyn understood, and sympathised; writes that 'for almost twenty years I too have plotted and planned my escape from Launceston,

yet here I am at the front window of my pretty but dilapidated house in a wild and pretty garden, breathing the scent of a soft rain

on jasmine while through the branches of my magnolia tree I watch the patina of rooves in the valley flattening themselves, or

seeming to, under a lightly leaded sky.'

'Still', (she adds, almost as an afterthought), 'the nearness of the Gorge is one of the bars of my prison. Early in the day,

before the tourists and before the cable cars start creaking overhead, when a mist, low on the water, softens the edges

of the rock and blurs the willows, the Gorge has that hushed, still quality of a Japanese woodcut. And where else could

diehards like myself brave the stillness and focus the mind with an early morning plunge into freezing water

in an almost wild place five minutes from the central post office?'

Carol Patterson's writing — Carol's compulsion! — continues unabated, with the publication of a novel and three collections of short

stories.

But her talents aren't confined to the realms of literature, a strong social conscience propels her towards

engagement in various activities aimed at making a difference in the community. In 2018 she organised a

Concert

for Refugees at the Moonah Arts Centre in Hobart, featuring, among others, the Tassie Nannas, 'an amazing group

started by two

Tasmanian grandmothers who

shared their horror and disgust for the Australian government's incarceration of children.' Carol spoke of the Tassie Nannas' commitment

to

doing what they can to give a fair go for refugees seeking asylum, especially those in offshore detention centres. 'They knit, every

Friday lunch time in the mall, you can go down and see them there any time and have a chat. And every Thursday in Devonport....

Don't be fooled by their mild demeanour: we have amongst us armed urban guerillas!'

Carol Patterson's writing — Carol's compulsion! — continues unabated, with the publication of a novel and three collections of short

stories.

But her talents aren't confined to the realms of literature, a strong social conscience propels her towards

engagement in various activities aimed at making a difference in the community. In 2018 she organised a

Concert

for Refugees at the Moonah Arts Centre in Hobart, featuring, among others, the Tassie Nannas, 'an amazing group

started by two

Tasmanian grandmothers who

shared their horror and disgust for the Australian government's incarceration of children.' Carol spoke of the Tassie Nannas' commitment

to

doing what they can to give a fair go for refugees seeking asylum, especially those in offshore detention centres. 'They knit, every

Friday lunch time in the mall, you can go down and see them there any time and have a chat. And every Thursday in Devonport....

Don't be fooled by their mild demeanour: we have amongst us armed urban guerillas!'

The evening continued with

Betsy Hanson and the Nourish

Women's Choir 'whose music you may have already been blown away by', Carol remarked, 'and if you haven't, you're certainly going to be blown away this

time.' Memories 'of another group of boat people, the Dunera Boys' followed, as did celebrated poet Sarah Day who read

a short selection of her exceptional poems. The evening ended with the recital of 'A letter from Manus Island' by Behrouz Boochani (still locked up

on the island

at this stage). 'For many months, the refugees living inside Manus prison have had to endure extraordinarily oppressive conditions

orchestrated by the Australian government....'

Carol Patterson's most recent short story collection — Vanishing Point — will be launched by Robyn Friend this Wednesday, 10th March, 2024 at Quixotic Books in Launceston at 5:30 pm and promises to be a memorable evening of readings and discussion.

Carol Patterson deserves much wider recognition for her brilliant mastery of the short story form.

Each story immerses the reader in an entirely different' vividly depicted setting with complex and contrasting

characters. Patterson brings these characters to life as they confront a range of human dilemmas and emotional

challenges. Her work is superbly crafted with control of syntax' voice and style.' - Janet Upcher

Carol Patterson deserves much wider recognition for her brilliant mastery of the short story form.

Each story immerses the reader in an entirely different' vividly depicted setting with complex and contrasting

characters. Patterson brings these characters to life as they confront a range of human dilemmas and emotional

challenges. Her work is superbly crafted with control of syntax' voice and style.' - Janet Upcher

'In these stories'

there is a voice of wisdom' a voice of experience' a voice of clarity. The author has tremendous sensitivity to

the characters' which allows her to breathe true insight into every scenario. They are the kind of people one may

meet in day-to-day life and often encourage us to pause and reflect on our own experiences in comparable scenarios.

There is a dynamic interplay between the physical surroundings and history of each narrative with the impact on the

characters' thoughts and reflections. Above all' the writing has grace and elegance.'

Dr Paul Goodey-Adevisyan