RALPH WESSMAN | NORTH TO GARRADUNGA

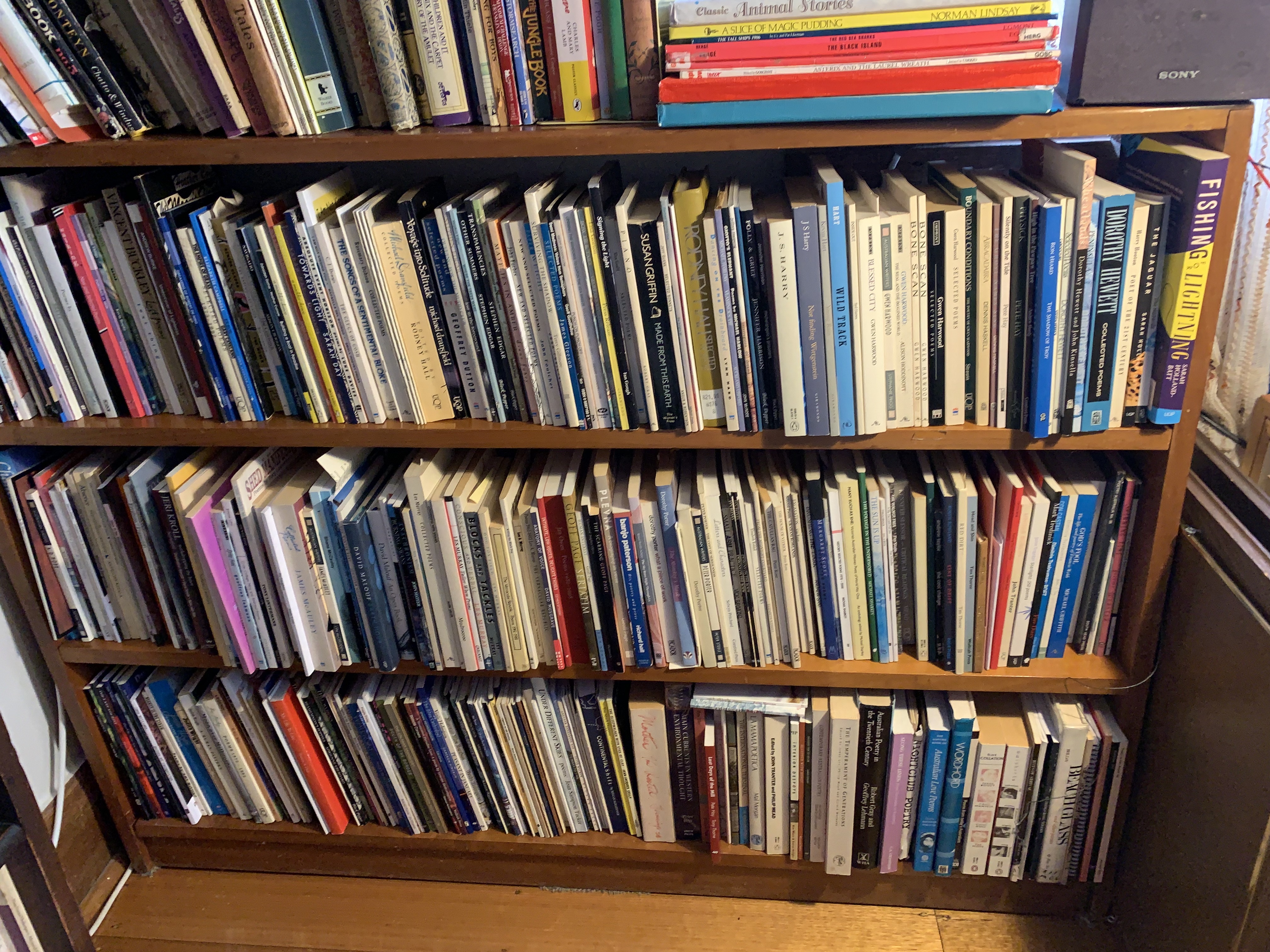

My bookshelves

A conversation with Anne Kellas

Poet Anne Kellas has lived on the unceded land of Hobart/nipaluna since 1986, having spent the first half of her life in South Africa and the UK.

Her book Ways to Say Goodbye was launched by Sarah Day in Hobart 21st September at Fullers Bookshop, and by Jane Williams in Launceston at the Tasmanian Poetry Festival on Saturday 7th October.

In compiling this interview, we chatted by phone and email and I visited Anne at home in Hobart where we planned our 'tour of her bookshelves.'

Ralph Wessman

So, where do we start?

Anne Kellas

Well, being a librarian, I’ve got my books classified into sections.

Old 'uni' bookshelf from my childhood and youth

This bookshelf is my oldest, it has travelled with me from my childhood, as have the books which are from my childhood and from youth during university days.

The pic above is of its top two shelves. It is mostly works from the English canon with a few extras. Basically the contents of these shelves has never changed, except that I have added a little to the French section, as you can see from the Michel Houellebecq below.

This bookcase has gradually grown to include a few American collections but there is a newer American section elsewhere. And likewise the German section here does not include my Paul Celan books. which are in a separate area, in my favourite bookshelf which we will get to later. It's reached full capacity now.

Looking at your bookshelf from its earliest days and noting the inclusion of your German and French sections, I suspect you've a strong European outlook?

I suppose that it might seem so because I am not so embedded in the Australian literary context, where perhaps I haven't read as widely as I might have. My grounding in the poetry that I read in my youth at university – and through my Mum at home – was mostly international in scope. The interest in German was pretty powerful, the literature that we read thanks to particular lecturers was really wonderful – the full panoply of German literature.

I suppose my taste has developed from a different origin; it's also the influence of the prose I've read. I think a lot depends on one's broader reading, not just the reading of poetry.

In retrospect it seems to me that in South Africa at the time I lived there, there wasn't as much South African poetry to read; it seemed such a small literary world. And by contrast, when I came to Australia I noticed the leisure that Australians had to devote to their writing. In South Africa – writers would be devoting their time to political issues. Which led, in time, to the local literary world expanding to include black writers. I have always been mindful of Nadine Gordimer’s admonishment to South African writers to be 'more than a writer'. I guess that now, having lived here for more than half my life, I am no longer a South African writer but I still feel one has to be more than a writer.

Judith Wright's conundrum – needing to write but feeling the need for political involvement even more.

Yes, that would definitely be the case.

Psychology and philosophy

I'm interested in Jungian psychology. Both Ira Progoff, who wrote the wonderful book on journal writing called, At a Journal Workshop, and Robert A Johnson, (Owning Your Own Shadow, HarperCollins, 2013) were students of Jung.

What initially drew you to Jung?

Aah ... well I was always interested in Jung's psychology, and interpretation of dreams and symbols. I had a book back in the seventies called Man and His Symbols, I suppose it coincides with my interest in Blake as well, that which comes from the psyche. I’ve also had the privilege of working with some Jungian therapists – so I suppose that also influenced me. In Ways to Say Goodbye, I mention one of Jung's followers Robert A. Johnston, who’s written a lot about myths and fairy tales in terms of modern man. In his book Owning Your Own Shadow, Johnson speaks of poetry as being of immense use in that it is 'the task of the true poet to take the fragmented world that we find ourselves in and make a unity of it'. I just find reading from that perspective really feeds something in me.

In recent years I have been collecting more books on philosophy, which I tried to study in my youth but I was too distracted to go deep. I've always been interested in the existentialists. On Consolation by Michael Ignatief is a magnificent book, not strictly philosophy as he is a historian.

Then, after I did my thesis, I became very interested in existentialism … well I’ve always been interested in existentialism. So I have … John Berger, and Walter Benjamin, who's the person I’m reading at the moment. Or trying to read!

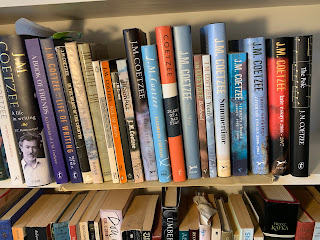

Fiction: J.M. Coetzee, Gerald Murnane, and Ivan Vladislavic

I think fiction writers have had a greater influence on my writing than many of the poets I so love. In my youth it was Doris Lessing's work, and her prophet-eye for the future, in books like Briefing for a Descent into Hell, a psychological thriller that to me foretold the unwinding of society that was to come.

A big part of this bookshelf consists of every book that's been written by J.M. Coetzee. And then his compatriot Ivan Vladislavic is inspiring. I've a copy of just about everything he's written and recently ordered his latest book, Distance.

For the past two decades it has been J.M. Coetzee's fiction that has absorbed me, fascinated me. Somewhere in his autobiographical book, Youth, part of a trilogy, he describes the moment where he himself gave up writing poetry for the more relaxed waters of prose: and he writes, "Prose, fortunately does not demand emotion: there is that to be said for it. Prose is like a flat, tranquil sheet of water on which one can tack about at one's leisure, making patterns on the surface”. I have hopes one day to tack about on those waters too.

I love Coetzee's essays, they have served as introductions to so many writers I've grown to love.

This is my collection of Gerald Murnane's writing: I also have his recent collection of poetry but it is his prose I am drawn to. Ah the Letters of Aldous Huxley, that's my mother's book. I have a few of her books, dragged across the planet with me as reminders of her deep reading life.

Whenever I can't read poetry, I settle back and read Gerald Murnane, I just wish I'd discovered him a lot sooner. I’ve placed Murnane alongside Coetzee because I see them in the same way, writers in a similar vein – in a category of their own really, I don’t know other writers who write in their way.

I began reading Murnane some years ago and I think I have everything he's ever written. I've lived in that mind for a long time. Maybe that’s why Michael Sharkey, in his review of Ways to Say Goodbye, said I had a sense of the mind as its own place.

There is something about the pace of the prose in these three writers (Coetzee, Murnane, Vladislavic) that puts them in a class of their own. There is no striving for effect. There is no clutter and artifice. There is instead an almost spiritual simplicity to their style of writing.

For me, both Coetzee and Murnane would seem to be writing from their own lived experience, or indeed seem to set out from that perspective, but then they do something remarkable in terms of the subjective perspective, in terms of the atmosphere and worlds they create. The nearest I have come to explaining what I mean is what the philosopher Dilthey says of poetry: the origin of a work might be in lived experience but it takes on another deeper dimension in the process of the writing. The perspective from which they write feels as if it’s first person autobiographical but it is not. I am told it’s called free indirect discourse, or ‘style indirect libre’ in French narratology. For me, it is at once a generalised, objective perspective, and a subjective perspective in that we are allowed to see from within the subjective authorial being. David Attwell the Coetzee scholar has explained it to me like this: “[The author] honours his reader, by taking us so deeply into the character via the textures of the narrative voice, thus allowing us, or requiring us, to form a judgement.” From this vantage point, in the case of both Coetzee and Murnane, comes something unique, and compelling.

The imaginative mind working its spell on you again.

I think so ... these prose writers – Ivan Vladislavic, J.M. Coetzee, and Gerald Murnane – write from a perspective that's really interesting to me. It's not the omniscient author, and it's not the personal pronoun but it's a universal perspective that I find is like... an aerial view. I had this in mind when I was writing the poem, ‘A Document of clouds’.

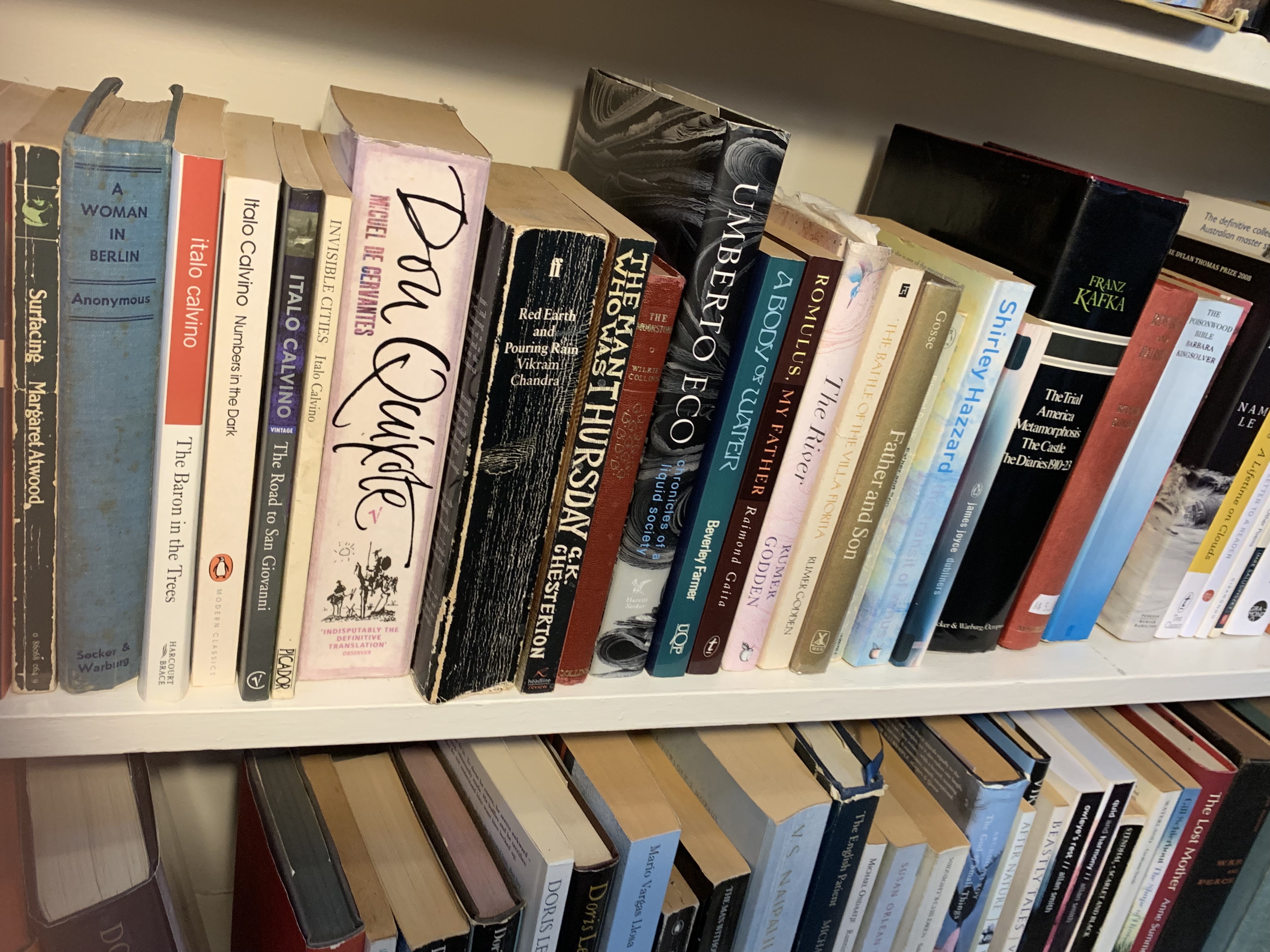

And then there are lots of novels down there. Doris Lessing ... again that's a sort of landscape of the imagination ... surrealism ... writers who allow their imagination to take off. And classic writers like Cervantes, Umberto Eco....

More fiction

Almost all the fiction we own is in my husband Gile Hugo's study. Giles has read an enormous amount of fiction over the years. During the time he reviewed books for The Saturday Mercury, he read 200 books a year ... I could never keep up that pace. I have a small batch of fiction in my study.

A huge influence on me was the writing of the Beats – Gregory Corso, Ginsberg, but especially Jack Kerouac. More than On the Road, it is his novel, Desolation Angels which I re-read every now and then. I probably read Anna Kavan at about the same time.

I have always loved Italo Calvino, and Michael Ondaatje is one of my most favourite writers, both as a novelist and more especially as a poet.

I like to dwell with a book and afterwards to have it with me, as if it is a person I have come to know. Very occasionally, I return to a writer I loved long ago, like Lawrence Durrell, but something of the delicious joy I experienced from reading The Alexandria Quartet when I was 20 vanished. The book remains on the shelf though, an emblem of that feeling.

Something from The Alexandria Quartet that has remained with me throughout my writing life – and has guided my writing all these years – comes from the 'Workpoints' or snippets of left-over phrases and images that Durrell inserts between the four interlocked novels: 'You have to put yourself into deep soak, psychologically speaking'. And come to think of it that might help explain my interest in psychology.

Missing from the shelves: The Beats and James Joyce. Giles has these. I really love Joyce. Yes, I think fiction has been a huge influence on my work.

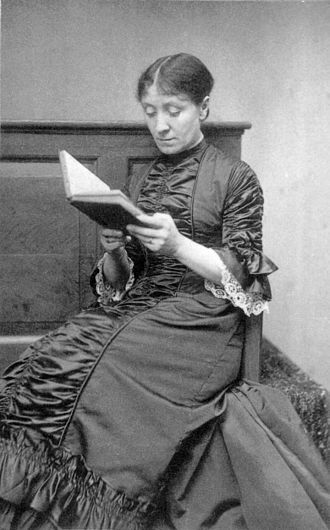

Also on this bookshelf I’ve one tiny section of Pre-Raphaelites … William Morris, that whole crowd ... and some were my Mum's relatives. A distant aunt was one of the Macdonald sisters – all four of the Macdonald sisters married a Pre-Raphaelite – one was the mother of Kipling, another was the wife of Edward Burne-Jones. That's my Mum's connection, she used to go on and on about it and I wish I’d listened to her properly.

Also on this bookshelf I’ve one tiny section of Pre-Raphaelites … William Morris, that whole crowd ... and some were my Mum's relatives. A distant aunt was one of the Macdonald sisters – all four of the Macdonald sisters married a Pre-Raphaelite – one was the mother of Kipling, another was the wife of Edward Burne-Jones. That's my Mum's connection, she used to go on and on about it and I wish I’d listened to her properly.

Georgiana Burne-Jones, née Macdonald c.1882,

photographed by Frederick Hollyer

Your mother's literary influence is obvious from the number of poems mentioning her within the first section of Ways To Say Goodbye – ; 'The Memory Garden, Revisited', 'Transaction', 'Travelling to My Mother Last Century'....

Yes, I inherited my love of writing and reading from her. My mother was a melancholic who spent most of her life in bed reading. She was fascinated by the Bloomsbury Group, read their biographies. Our only entertainment on a weekend was to drive from our city to the Johannesburg library and stagger home with piles of books. She'd wangled herself a library card there.

And your line, 'her Vita Sackville-West, the lighthouse, waves' ... an allusion to the relationship with Woolfe?

Oh yes, it was a deliberate reference.

I find the Bloomsbury Group fascinating – not least, I suppose, because of John Maynard Keynes' influence in world economic affairs: what's an economist doing amongst this set!!! But amidst all this was your father. Where did his literary interests lie?

My father read cowboy books.

What was he like? I note the lines from your poem 'The Memory Garden Revisited' where you write

My father stayed at home. Or went to work.

Made himself absent in some way.

A silent man. Mostly angry.

A poet friend once said to me to leave out those last five words. A poem doesn't have to tell everything; but he – my father – was a puzzle. My dad would have done anything for my mother, he absolutely worshipped her. And she treated him really badly. They'd have barnies with each other, and I’d always take my mother’s side. My father and I would have these fights and he’d drive me to school and we'd still be arguing. He'd drop me off and we'd slam the door – and then we’d catch each other’s eye and we'd both be smiling.

He saved my life when I came back from England very depressed.... He sat me down in the kitchen, and said I absolutely understand you, totally understand where you're at. And he set me off on the track to go to Cape Town. He just really understood me.

And he was also a fan of my writing. Now that's the funny thing, here’s my mother, so well educated and all that, and my Dad reading cowboy books, but he was the one who rescued my poems when I threw them away in the rubbish bin, while my mother would hide my first book, Poems from Mt Moono in case her friends picked it up and read it.

A collection of books on writing memoir

I am collecting books towards writing the story of our late son François using both my thesis and my poetry and my notebooks ... but it could be that Ways to Say Goodbye, which contains some poetry from my thesis, will be all I manage to accomplish in the time left to me. We'll see. Some of the books on writing memoir were given to me by our son Daniel, and some I discovered thanks to friends or writing workshops.

What you can't see of the spines in this photo are some excellent booklets from SANE Australia, which helped us cope when François was so ill.

American poetry; Australian poetry, and my bedside table reading

I have all my A4 folders and files high up above my uni bookshelf; on these deep shelves, there's an overflow of books. The shelves are big enough to house The Red Book, in view below, which contains Jung's paintings (mostly mandalas) from the period when he withdrew and painted his way out of a depression.

But mostly this photo shows my very tiny American poetry collection. It’s patchy to say the least. Older American poetry such as collections by The Beats, and the New York School, are in my uni bookshelf described earlier. The Louise Glück collection and her essays, and Mark Doty, are probably the most recent. There’s Robert Duncan, and H.D. My high school English teacher read me her poems. I love the Imagists. The H.D. Book, by Robert Duncan, is inscrutable. He was a huge fan of H.D. but what he wrote is to me very turgid to read, very difficult and complicated. But I'll read it when I want to twist my mind … though I’d much rather read her poetry than read about her.

I depend a lot on anthologies for my poetry reading as it gets expensive buying books. I hope to be buying two new books from Kevin Hart (do we call him an American now?) due out in September – but it is no use listing all the books I wish I could buy.

Anyhow that is what I have of American poetry; a new Ashbery is on the bedside table.

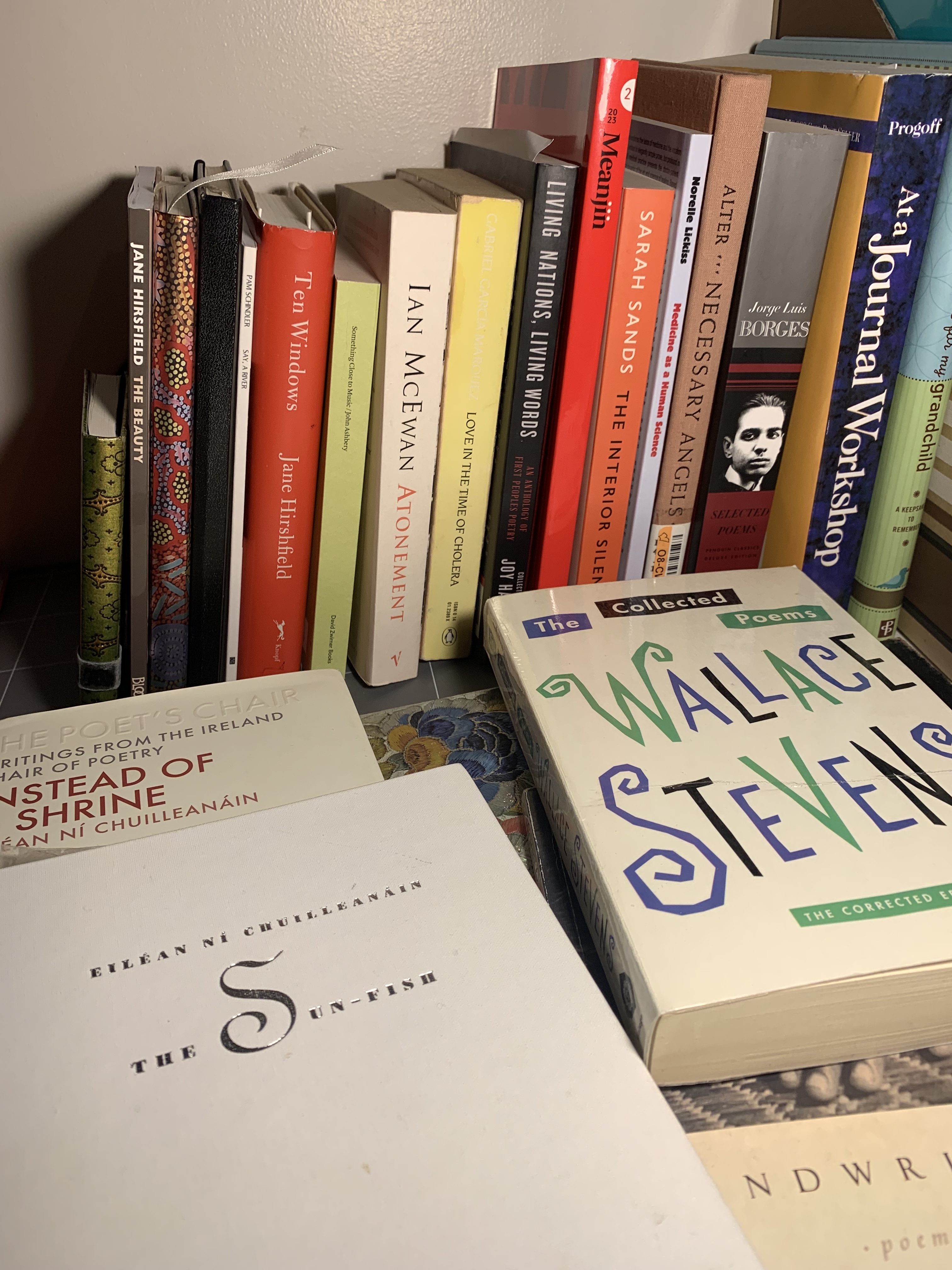

My bedside table's current offerings are below.

What isn't in the picture is John Carey's anthology 100 Poets, which is currently living in my handbag.

I am re-reading Jane Hirshfield, a slim volume of her poetry and her essay collection called Ten Windows, and Wallace Stevens is always there, as is the Irish poet Eilean Ní Chuilleanáin, whom Pam Schindler introduced me to. (Pam's new book, Say, A River, is there too. I recall Chris Wallace-Crabbe saying something along the lines, poetry books are so slim, they fill shelves slowly…. )

I am re-reading Jane Hirshfield, a slim volume of her poetry and her essay collection called Ten Windows, and Wallace Stevens is always there, as is the Irish poet Eilean Ní Chuilleanáin, whom Pam Schindler introduced me to. (Pam's new book, Say, A River, is there too. I recall Chris Wallace-Crabbe saying something along the lines, poetry books are so slim, they fill shelves slowly…. )

By the way, here is a gem from Ní Chuilleanáin's essay, Instead of a Shrine, which you can see lying on the table: it has this wonderful insight: there are about poems, and there are instead poems.... To me, that just about explains everything.

Necessary Angels, next to Borges, is a book by Robert Alter, about 'the prismlike radiance created by the association of three modern masters: Franz Kafka, Walter Benjamin, and Gershom Scholem. The volume pinpoints the intersections of these divergent witnesses to the modern condition of doubt, the no-man’s-land between traditional religion and modern secular culture.'

Below is my Australian bookshelf, which has far too many books for me to single out very many poets without sounding as if I am excluding someone. The collection is a bit unbalanced – a lot of them are from the late 80s to about 1995, which was the period when Giles was reviewing books. He would get sent heaps of poetry, and as a newish person here that helped me to learn about Australian poetry. As a collection it’s not nearly representative enough to be made much of. Since that time, it's grown – I've bought individual collections ... Robert Adamson, Jan Owen, Mark Tredennick, J.S. Harry, Kevin Hart, Sarah Day, Michael Sharkey, Michael Dransfield, Francis Webb, a little bit of John Tranter, Stephen Edgar ... a number of anthologies. Recent additions are The Jaguar and Fishing for Lightning by Sarah Holland-Batt. And Michael Sharkey recently sent me some gems from the past from his own collection.

Being a librarian my books are mostly arranged A-Z by author, and then I began a section of Tasmanian poetry A-Z by author, but finding things is hard as I have to look in two places...

There's a kind of voice I hear in Australian poetry, in that I feel there is some poet whom everyone in Australia has read and I sometimes hear that voice come through in certain contemporary Australian poets. I guess that would be OK except that instead of hearing an authentic voice of their own, there is a note of sameness I hear. Sometimes it is not so much a voice but mannerisms, patternings. This is something that has put me off a lot of contemporary poetry – of any kind, from any place. It is as if there comes to be an idea of what a poem should be, and then you see that again and again and poets stick to it instead of innovating. I am not saying I am free from blame in this regard, it is merely what my ear hears and likes or dislikes.

Francis Webb. He's one of my very favourite Australian poets.

And underrated?

No not underrated but never mentioned much. And I think he's a genius. I have his Collected Poems, and some of my favourite poems ever are by him. His is a voice that's unique, that's pure, that's lyric at its highest. It's not trying to be fashionable and make a point or underscore anything.

Why's he unfashionable, do you think? Too complex for popular tastes?

Well he does have a following, people who follow or read literature.... Maybe he has a reputation for being difficult, I don't know. Maybe its religious overtone makes people avoid him. Maybe people only read contemporary work....

OK. And you mentioned Dransfield?

Well then again I think so much comes down to the unique voice. It doesn't have an echo of somebody else. I get the feeling that in Australian poetry there's a lot of imitation. It's as if the poet hasn't found their own voice. What interests me in any poet, it doesn't matter what country they're from, is that unique – I want to say eccentric – flavour that defines them. Again in Dransfield, there's what I said earlier about a kind of freedom – I don't know that he ever redrafted things – his ability to pour out beautiful ... and sometimes not beautiful ... work on such a scale. Aaah! ... he's another one of those genii, I think – but again, not much talked of now....

I also get amused by the fact that in the UK Les Murray is thought of so highly, because people only read his poetry and they don't know the political backstory and contexts perhaps. Whereas here, because of those, they don't read his poetry, and I find that quite sad.

Next is a very small South African section that's on my bedside table at the moment, I was lucky enough to receive a bundle of poetry books from South Africa from Robert Berold, a wonderful poet, a few years ago when their postal service still worked.

Ralph, you would be very interested in Robert Berold's work in fostering poetry over there, as a small press publisher, journal editor, lecturer, mentor. He is himself the writer of wonderful poetry. In so many ways he has served the South African poetry scene in the same generous way I experienced Lionel Abrahams' service to poetry. In particular, Berold has fostered the writing of Black writers, and his masters-level course at Rhodes University in Grahamstown sounded wonderful to me. He’s retired now but still teaches, writes, mentors people. A representative anthology, published by his publishing house, Deep South, is In the heat of Shadows: South African Poetry 1996-2013.

Ralph, you would be very interested in Robert Berold's work in fostering poetry over there, as a small press publisher, journal editor, lecturer, mentor. He is himself the writer of wonderful poetry. In so many ways he has served the South African poetry scene in the same generous way I experienced Lionel Abrahams' service to poetry. In particular, Berold has fostered the writing of Black writers, and his masters-level course at Rhodes University in Grahamstown sounded wonderful to me. He’s retired now but still teaches, writes, mentors people. A representative anthology, published by his publishing house, Deep South, is In the heat of Shadows: South African Poetry 1996-2013.

When the bundle of South African books arrived in the mail, were you surprised at the nature and quality of the work, had the writing moved in directions you'd not foreseen?

Yes, it was an education for me, I hadn't been able to keep up with movements there.

It was lovely to see a huge range of work, and some really astounding women poets – I'm thinking of Joan Metelerkamp in particular. Marlene van Niekerk. I'd been aware of the work of Antje Krog, Ingrid de Kok, and, long ago, of the poetry of Ruth Miller whose work Lionel Abrahams introduced me to.

But there are far too many good poets in general in South Africa for me to single out people without running the risk of excluding someone excellent. I am no expert reader of South African poetry, I have been away too long and my book collection is sparse, apart from what the ever-generous Robert Berold sent me in recent times before the postal system there began to fail. I know some poets' work better than others, Kelwyn Sole's for example. He and Chris Mann (the South African poet) were at University of the Witwatersrand when I was there, but I was too shy to ever speak to them. But I chat with Kelwyn Sole on Facebook now.

Only last week, Ivan Vladislavic introduced me to the work of P.R. Anderson, another very fine poet who teaches at the University of Cape Town and is published by Dryad Press.

I get the impression that writing in South African poetry retains its own particular vitality and strength. While a lot of the subject matter is driven by current events, I think many of their poets are producing work that will survive beyond the confines of their political context. And on that topic ... I believe Sarah Day has written a very interesting thesis that explores what it is that makes a poem last beyond its temporal grounding or surroundings in world politics or events. I quite like reading theses and hope to read hers one of these days.

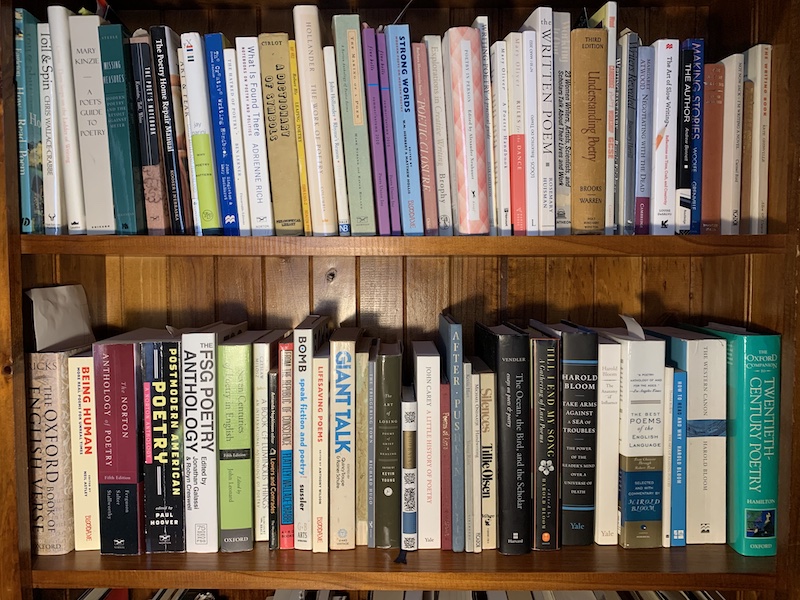

My favourite bookshelf: Anthologies, and writing about writing

I really love reading books about the writing process. I love teaching writing, and some of my most treasured books are about the writing process. Of the three photos below:

The first shows the top shelf which is books about writing poetry (an expanded view of which is given in the bottom two photos) The first photo shows the second shelf with poetry anthologies and a fair smattering of books by Harold Bloom.

These next two are close-ups of the books on writing poetry. I have a fair amount on form in poetry, although I myself write mostly free verse.

For many years my favourite book was an old one, Cleanth Brooks and Penn Warren's Understanding poetry. I'd say I got most of my grounding in poetry from that book.

I am realising now what’s missing thanks to this interview! Poetic Closure: A Study of How Poems End, by Barbara Herrnstein Smith… and Writing as a Way of Healing: How Telling Our Stories Transforms Our Lives, by Louise DeSalvo: that book got me through my thesis. DeSalvo is an expert on Virginia Woolfe.

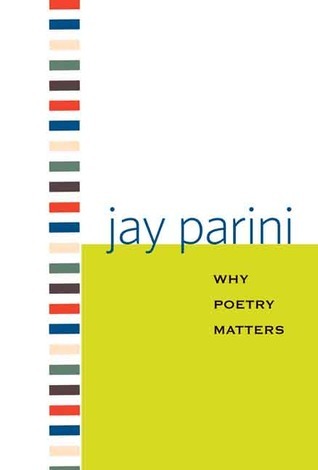

AND then I get on to my favourite section, which is – books about the phenomenon of poetry, and its mechanics, its innards. I’ve always been interested in that. Although I don’t write formal poetry, I am interested in versification. One book along those lines is by Jay Parini, called Why Poetry Matters.

I've a copy of Parini's book too; which leads me to broach the topic of the usefulness – or not – of poetry.

Let me turn this question around like a many-sided diamond and answer it from as many angles as I can, because it is a useful question!

I don't think poetry is useful for anything, but it is of use, if that makes sense. It's of use in the way sitting in the bright sunlight on an icy Hobart morning is of use in all kinds of subtle ways. I don't think that the writing of poetry can be useful for changing the world or for changing me, but I believe poetry does change things, if only by merely being there, and so it is of use. The poem begins its life, useful or otherwise, when it is read by another. And at that point you could argue for the usefulness or otherwise of poetry. I am not a huge fan of Mary Oliver, but I have always liked these words of hers from A Poetry Handbook, they go to the core of your question: she says poetry is 'something as necessary as bread' – I don't think she needed to add 'in the pockets of the hungry'.

I can give two examples of the usefulness of poetry, both from Jay Parini. The first is from Why Poetry Matters, where he

says poetry 'makes the invisible world visible'. If that's not useful then what is? It's what I try to do, I think. The second is a very practical example which he gave to

Ramona Koval in an interview about that book quite a while ago. Jay found himself having to administer some restorative justice to a group of

young people. They had been found vandalising the Robert Frost House which Jay was involved in preserving, and they were given a choice: sit

through a lecture on poetry or gain a criminal record. Needless to say, he lectured them on Frost's 'The road not taken', and his lecture (and the poem)

had a transformative effect on their lives.

I can give two examples of the usefulness of poetry, both from Jay Parini. The first is from Why Poetry Matters, where he

says poetry 'makes the invisible world visible'. If that's not useful then what is? It's what I try to do, I think. The second is a very practical example which he gave to

Ramona Koval in an interview about that book quite a while ago. Jay found himself having to administer some restorative justice to a group of

young people. They had been found vandalising the Robert Frost House which Jay was involved in preserving, and they were given a choice: sit

through a lecture on poetry or gain a criminal record. Needless to say, he lectured them on Frost's 'The road not taken', and his lecture (and the poem)

had a transformative effect on their lives.

Speaking personally though, I don't write poetry because of anything like its use or usefulness. I don't write with any idea at all of contributing to a canon of any kind and in fact have to do the opposite and deliberately set aside any self-conscious thoughts about writing or I am paralysed.

There is no teleological dimension for me when I write. I don't write poetry for catharsis, that's a task for the diary or daily journal. I prefer to think of the process of writing a poem as one of setting out to discover something unknown. You set off blindly not knowing where you will end up. And how can that be useful except for the fact that it does things on a metaphorical level. It's a place where I meet nothingness, where nothingness comes to be. (I think it was Paul Celan who said this, but I cannot track down the quote). And in that strange space, the poem happens, unbidden, never at my command, and presents me with itself, with material to make into something. For no reason at all. The poet as maker.

If I am pressed a little further on this matter of usefulness, for me it is always in terms of writing that will be read by another person.

Here we get the poetry of witness, which is a whole other topic too large to address here, and also, poetry as a way to do the inner work

of the soul. One of Jung's followers, Robert A. Johnson speaks of poetry as being of immense use in that it is 'the task of the true poet

to take the fragmented world that we find ourselves in and make a unity of it'.

What's next in this section?

Well, here's a collection called Poetry in Person – Twenty-Five Years of Conversations with America’s Poets. It's my most precious book. Our son Daniel gave it to me.

Pearl London held poetry workshops in New York where she invited a poet to come in and talk about the composition of a poem; she would prime her workshop attendees with a draft copy of the poem, and then invite the poet to come along with all the relevant drafts and explain how the poem grew into its final form. Poetry in Person contains the written transcriptions that she made of those workshops. She had people like Edward Hirsch, Galway Kinnell, C.K. Williams, Charles Simic, Louise Glück, Derek Walcott, Robert Hass, James Merrill, Robert Pinsky, come to her workshops to explain their poems … so it’s a gem. John Ashbery was one of her initial presenters at her workshops.

It's a remarkable book, and I use it for teaching because it has photographs of the poets' drafts, and you can see their scribbles in the margins, and their crossings-outs – as well as the final poem.

I'm curious, what's the benefit to you of your close observation of others' work processes?

Oh, I am not a huge fan of 'close reading' but this particular book is wonderful for teaching others. And myself. I get a lot of encouragement from it. To see how they play around, just the list of words that rhyme in the margins – the inner workings of the minds of the poets. The scribble, the casual, free-wheeling approach, playing with the poems – and also very serious and incisive.

And here's one that Tim Jarvis at Fullers Bookshop suggested, he said, "Anne Anne I've got a book for you!" – it's called The Hatred of Poetry by Ben Lerner, published in 2016, and it's partly about why poetry's not more popular now....

And did you enjoy it?

Yes, it was good, it was good. It explains the poet’s dilemma with finding an audience.

And there are books I have of criticism, of literary theory. I enjoy that.... Books like William Logan's The Undiscovered Country: Poetry in the Age of Tin, it's his book reviews that he's published. And there's a book I bought by Helen Vendler, The Ocean, the Bird and the Scholar – essays on poets including a chapter on Wallace Stevens where she explains him most deeply and cogently, but I haven't managed to read too much of it yet.

Next I have a book called Silences, a book by the American writer Tillie Olsen about the silences in women’s writing; how a young poet will appear and she’ll be wonderful … and then you don’t hear from her till she’s sixty, because she’s been busy working and raising kids. I’ve lived with that book for … forty years … and it’s just inspired me to not give up, I suppose, because I’ve had long silences in my career. That book has kept me focussed.

Next I have a book called Silences, a book by the American writer Tillie Olsen about the silences in women’s writing; how a young poet will appear and she’ll be wonderful … and then you don’t hear from her till she’s sixty, because she’s been busy working and raising kids. I’ve lived with that book for … forty years … and it’s just inspired me to not give up, I suppose, because I’ve had long silences in my career. That book has kept me focussed.

In mentioning you’ve found silences in your work, have you ever managed to sit down and write about what it is that's silenced you? Or have you simply picked up again from where you left off?

It wasn’t that anything silenced me, it was that there was no time to write. When I did resume – always after a gap – I couldn’t continue from where I'd left off because things had changed from book to book. My style changes from book to book…. That’s nothing unusual though.

Okay, sorry for interrupting.... Where were you heading after Silences and Tillie Olsen?

I was taking a little sidetrack. I had a different kind of silence myself. When I left South Africa, I was about to be published in New York in Columbia: A Magazine of Prose and Poetry. Nadine Gordimer had asked Lionel Abrahams for work she could put into a special issue of the journal reflecting contemporary South African writing. I was one of the poets selected, and that’s where my career was when I came to Australia. But when I arrived here, I had zero, zero connections with Australian poets and poetry, it felt I had to start all over again.

Yet from zero connections, you picked up pace pretty smartly; developed a website along with the literary blog 'North of the latte line', established Roaring Forties Press and published books by Lionel Abrahams and Geoffrey Dean....

It wasn’t such a quick transition. I’d arrived here in ’86. My website 'The Write Stuff' was established in 1995, 'North of the Latte' line was active in the early 2000s. I’ve explained a lot about this period in another interview which was conducted by Pam Schindler – it is due to appear in the next issue of the journal, Neither/Nor.

How did it feel to be an early adopter of the internet?

I was an enthusiastic evangelist for everything web. In those early days of the internet, there was a brilliant techie newsletter called 'The Red Rock Eater'. It taught me so much, helped me learn all about the new world of the net. Then its editor, Phil Agre, vanished. No one knew what had happened to him – Wikipedia tells me he was an AI researcher and humanities professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. Some of his dogged followers set out to solve his missing person's case, and he was found living in a desert, off line, off grid, off everything short of leaving the planet. He said, OK now you have found me go away. His was one of the brightest minds of the early internet. We are seeing something like this now too, with AI experts who know what it is and does coming out and speaking out against it and asking for legislation to be created to control it. At this point in time I am somewhat hopeful that governments will have time to put some legal frameworks in place to keep AI in its place. It will take unilateral effort and commitment.

Well, as to AI.... Apparently there's a new Beatles' tune featuring the voice of John Lennon, 'extricated' courtesy of AI from a previous recording. Paul McCartney's suggested that some aspects of AI concern him, but it's '... kind of scary but exciting, because it's the future.' Nick Cave on the other hand has been horrified to hear songs created by AI 'in the style of Nick Cave', suggesting songs arise out of suffering 'by which I mean they are predicated upon the complex, internal human struggle of creation and, well, as far as I know, algorithms don't feel. Data doesn't suffer.'

Well Paul McCartney is in a position where he can give the go-ahead for AI, and can more or less control the output of the musical concoction he is producing – but 'control' is the key issue in that case. I think McCartney is being careless in saying 'We'll just have to see where that leads' because we do not know where it leads. Control is the issue.

You know, I sent ChatGPT an enquiry asking for some background to the Tasmanian Poetry Festival, but as far as that particular enquiry was concerned, Tim Thorne hadn't ever figured in the festival's history. The programme listed your name, and that of Adrian Caesar, as joint festival founders. Just one version of its output, admittedly.

This terrible error it made about the Tasmanian Poetry Festival – which had its origins in the hands of the wonderful and inimitable Tim Thorne – is probably because Tim avoided the internet mostly, so ChatTPT would not have found enough about Tim to generate anything like accurate information about him or the wonderful festival he founded. The thing about ChatGPT is that it is a natural language model, and not a search engine – but we are tending to look on it as a kind of Google search engine. ChatGPT is not intended to deliver 'results' in the way a search engine delivers results. It delivers 'stuff'. Any stuff. ChatGPT is just a calculator – but for words: it takes words (from sources it has been trained on) and throws them around into supposedly well-formed sentences, producing something like a patchwork quilt which it has composed out of likely words and phrases it has found or to which it has had access.

We are conditioned to regard information from machines as reliable and trustworthy. That might be so with the world of numbers and statistics, but with the realm of language?

I fear though that we are nearing a point where original content created by humans is becoming muddled up with the simulacra of the machine, with the latter seen as 'true' or correct – and superior – precisely because it is generated by a machine. The trouble is that something like ChatGPT can work with the rules of grammar sufficiently well to come up with simulations of language, text, but we forget they are just that: simulations. And those 'results' are not the equivalent of the real thing. I might be wrong but I believe real creative intelligence and the products that result from 'the complex, internal human struggle of creation' as Nick Cave puts it, cannot be equated with artificial intelligence and its 'creations'.

A closing thought on AI, from my wise son Daniel:

In Australia, 'Robodebt wasn't even AI; it was just bad algorithms given unjustified power – and real human beings literally died because of it. Yes, Stable Diffusion [a text-to image model] and GPT are problematic, but we actually need legislative protection from algorithmic abuse in general, not only when it's wired up to AI'.

OK ... to return to your first years in Australia and your involvement with a press, a website and blog ... I'm reminded of the illuminating interviews you conducted with John Tranter, Chris Mansell et al. Given you'd not been in the country for any appreciable length of time, I'm impressed by the ease of your literary adaptation....

I'd been here for four years, at that point, when I interviewed Tranter. It was such a different poetry world then.

But I was very very fortunate to have a close friend, Michael Dargaville, who introduced me to the work of Michael Dransfield, and John Tranter, and all the writers that were prominent names at that time. He grouped them for me: such and such belongs to that group, and this is the Generation of 68, and.... He made me swear never to submit a poem to Quadrant, but it was too late and Les Murray had already accepted something. He pointed me to particular poets to read. What all this did eventually was turn me to the New York school of poetry and then I spent a few years reading a lot of Americans. I usually find reading one poet leads me to something else, I suppose everybody finds that...

When it comes to poetry as opposed to, say, an interview, do you find yourself spending much time on research?

Oh, not for me. It's true I've added research at the back of Ways to Say Goodbye to expand on a term, and then Rose Lucas said hey why not let's put that into a Notes section instead of having footnotes. I don't research something and then write a poem. I might write a poem and then think, oh gosh I'd better check such and such. I think the most research I've ever done on a poem would be that one in the 'Various Angels' section of the book, 'On Jean-François Millet's "The Angelus" (1857-1859)' with the paintings by Millet and Dali. That research actually helped me finish the poem. I thought I had finished the poem and then I discovered that Dali was interested in that painting.... But with the poem'On Paul Klee's "Angelus Novus"', I did a lot of research about Walter Benjamin's fascination with the painting and then in the process of editing the poem, I did a bit of rewriting, after which the long bit of the poem just took off. I wouldn't say it came from the research, it's the poem saying hang on, I haven't finished saying what I wanted to say....

Could we revisit your interview with Chris Mansell? I'd like to put to you one of the questions you asked of her – about belief, faith, spiritual explorations....

Did I ask Chris that, oh gosh!

Faith was a blurry and very private thing in my family of origin, overshadowed by the fact that my mother had had Christian Science foisted upon her by her stepmother. Choose your own religion when you are an adult, she had said to me. I recall going to church exactly three times in my childhood. As a young person seeking something more in England, I tried all kinds of things. Do you want me to list them all? Zen Buddhism. Sufism. And back in South Africa again, Judaism. Christianity.

There are many roads to follow, and to me, they all lead to a supreme mystery of an encounter with awe, through prayer. An awe that is huge, beyond explanation in the confines of this paragraph. In the year 2000 I had to go to a conference for work in Jerusalem. I didn't have any kind of religious experience or epiphany there, but felt very much how ancient and imbued with history the soil is that we tread, in any land, every day, and how precious the idea of soul and human life and the spirit is. A hallowing of simple things, ritual, belief: these things are supremely important to me.

In writing, faith is a matter of alignment. I have to have three things in harmony: the life of writing and the life of the spirit and the everyday life. Each involve a kind of ordering, a kind of listening. And eventually, a trust. In recent times, to be honest, my faith has almost not survived; I don't go to church any more. My faith holds on by a thread. Maybe that's why I so love poets like Wallace Stevens, for whom faith was a tricky thing.

What his [François'] death has done to my belief system is something private. I still have my faith, but my belief is a matter for another day. My faith keeps me going in the way a clock is wound and keeps ticking; as long as my heart beats, I will have faith. My son too had faith, one he never lost, though like me I think his belief system failed. That is a big question. What do you do when your belief system fails?

The thing is Ralph ... there is me, and there is the poetry, and they are not the same.

So a question about my faith is kind of not a question about my poetry ... but I am happy to have a go at explaining something of my faith situation.

The poems come to me.

I sit down to write and it is as if there is an open field where nothingness comes to be ... and it is there I meet poetry. Or not.

There is nothing teleological about it.

I don't think now I am going to sit down and write about my grief or my faith or my anything.

And it is not catharsis.

I do not use writing as catharsis or as a way of processing grief or any other emotion.

I sit down and there is a blackbird.

Or the sound of a train.

Or I wake up with a phrase in the night.

Or there is nothing to write.

The poems cannot be forced and written on demand.

Which is hugely frustrating if one has any intentionality like, I must write another book let's sit down and write now. Because it does not happen that way for me. It happens via a very circuitous route that has much more to do with meditation and the psyche and being open to the unconscious.

Here's a book which once again I thank Daniel for giving me. It’s Robert Alter’s Book of Psalms.

I collect books about the psalms, I have always read the Psalms even in times when I cannot read the Bible, and find their musicality endlessly interesting. At the moment my faith is being revived by the wonderful poetic work of Robert Alter … I mention him in the Notes at the back of Ways To Say Goodbye as well. Recently a dear friend gave me the complete set of Robert Alter's biblical translations and it is one of my most treasured possessions.

I collect books about the psalms, I have always read the Psalms even in times when I cannot read the Bible, and find their musicality endlessly interesting. At the moment my faith is being revived by the wonderful poetic work of Robert Alter … I mention him in the Notes at the back of Ways To Say Goodbye as well. Recently a dear friend gave me the complete set of Robert Alter's biblical translations and it is one of my most treasured possessions.

Robert Alter is a classical scholar and translator of ancient texts. He is also steeped in the study of literature and poetry in particular. As a result, his translations of the book of psalms is the most lyrical, deep plunge into poetry one could wish for, with his rendition of the King James text forming the base line and the undertow being the subtext where he writes the scholarly notes underpinning the words of the psalms. It is here I discovered the phrase, 'The mute dove of distant places', to me, that's an evocation of helplessness and exile which I tried to capture in a poem in my new book, Ways to Say Goodbye. My first attempt at writing that poem was ruined by overwriting, and I eventually wrote a completely different poem, but the 'ur' poem is one I still hope to complete before I die!

I am not an evangelistic poet in any way. I don't think I write about faith. But I have always loved the language of the King James Bible and especially the Psalms.

Continuing with this bookshelf, I’ve a lot of poetry anthologies. And one of my precious ones – it’s published by Amnesty actually – is an anthology named From the Republic of Conscience, an international anthology of poetry … aaah, I’ve just found something inside it ... an essay by Chris Wallace-Crabbe called ‘Poetry and Belief’; which is a wonderful essay … I wonder why that got stuck inside there….

I've quite a lot of Harold Bloom, I’ve enjoyed his work over the years, and his anthologies that he put together of poetry from his own system of arranging poets in eras, for instance this one where he chose one poem from each poet at the end of their lives, it's called Till I End My Song: A Gathering of Last Poems, that's a lovely anthology I often dip into. Another of his I have is called The Best Poems in the English Language. I love his idea of the 'strong poet' – a 'strong poet' deliberately misreads their precursors, as opposed to others who simply repeat their precursors' ideas or styles.

Bloom too was a huge Wallace Stevens' fan.... And very interesting to me, for Bloom … excellence in poetry stopped after Wallace Stevens. I think he added John Ashbery to his canon, but after Ashbery no-one else met his standards.… Very strange.

I find I'm always collecting anthologies, I have the Norton anthology, the Oxford anthology, an anthology of postmodern American poetry and a new one, the FSG Poetry Anthology from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, but my favourite anthology is a slimmer one by Czeslaw Milosz, A Book of Luminous Things. An International Anthology of Poetry, I just think there’re such gems in that book, I often teach from it.

So much to appreciate....

Oh I'm very much a butterfly.

And I have a batch of books on another part of the bookshelf now, all about creativity and the mind and what spurs creative writing. Books like The Artist's Way, and another one – Freeing the Creative Spirit – about reviving creativity when it's vanished.... Some of them speak about going deep in a work, others are simply about writing exercises. One that goes very deep is Ira Progoff’s At a Journal Workshop: Writing to access the power of the unconscious and evoke creative ability. But that’s a subject for a whole other interview. I share that process of writing reflexively with my dear friend Libby Lamour in South Africa, in a dialectal, quite organised fashion.

You mention creativity, and I'm curious about the approach you take with the occasional poem where there appears to be an intentional mis-hearing on your part. You'll write, 'It was a mercy, said the river. / But I heard it as mystery, and agreed/ a mystery strange and alien....' You're allowing yourself permission to take off on a tangent?

I think that those mis-hearings are almost deliberate misreadings. They have to do with language and dipping in and out of a particular type of consciousness, so if you're writing from a deep consciousness and you've got into the flow and you're actually lost in the writing – you're not aware of what you're writing as it were, and then suddenly you wake up because you've written the word 'mercy' ... suddenly the letters on the page glare at you, and something in your mind plays. And you say 'mystery'... 'mercy', 'mystery', 'mercy'... and your attention comes out of that deep space to the surface of the page. And on the surface of the page, you start playing with the words. I might be making a mistake, but I allow myself to make that mistake to be there and I play with it. And that might hold true for some places, but it's not always a deliberate method of writing, it just happens. Sometimes I will cross those things out and they'll fall out of the poem, and sometimes they will stay. It's also a way of coming out of, say, seriousness, and making the poem a bit lighter. A bit of light and shade. It's playing with language.

Then we move on to Paul Celan, and Tomas Tranströmer....

Celan wrote in a spare form of German ... ?

He was writing in a style that was a very symbolic, spare and essential language, trying to avoid using the German of the Nazis, writing in a very pure form of the language that, for him, had no overtones to him of their speech, and of the suffering he’d seen.

I have lived with Paul Celan for a lot of my life: from my early exposure to his poetry when I studied German in my late teens, and then intensely in the past 20 years. I have Pierre Joris's recent marvel of a work on Celan's 'Meridian', a meditative essay on poetry which Celan delivered as a speech. Celan had carefully crafted the speech over many drafts, and Pierre Joris used those drafts along with the final text, in The Meridian.

I also have the massive recent translations Joris did of Celan's early work, and his last works. My favourite is still Pierre Joris's earlier collection, Selected poems of Paul Celan which was my constant companion as I wrote The White Room Poems.

At the time of getting that manuscript together, I wrote to Pierre and asked his permission to quote from the Selected, and that text appears as the epigraph to my poem, 'To get rid of the layer of snow' (a line from an interchange between Celan and René Char) in The White Room Poems.

I've been absorbed by Pierre Joris's translations for many years. I have read other people's translations of Celan – and with my knowledge of German and being a poet myself I find that Joris is just so much nearer that 'invisible original poem' than any other translator.

I gave a workshop in Launceston on the topic of translation of poetry as a way to approach the 'original invisible poem' which both the poet and their translator(s) are trying to reach. Which brings me to Tomas Tranströmer....

The idea of the invisible poem is not unique to Tomas Tranströmer, but he explains it well when he speaks of his close friend Robert Bly's translations of his work: Tranströmer says the interesting thing is that Bly's translations differ from other people's translations and he prefers them. Although they are less accurate in the sense of word-for-word translation, they are far closer to the 'original invisible poem' that lies behind the actual work. To me this is a miraculous and wonderfully enlightening concept. It explains to me the realm from which poems come to us. It explains to me the idea the philosopher Ernst Cassirer speaks of, that the work of artists also creates work in the symbolic world. That idea’s been steering me for the last two years, I guess.

And is reflected in Ways to Say Goodbye?

Maybe. It’s become a way of thinking about a poem as I work on it. When I teach, I always say to people, go back to your original draft because the original, first draft is the closest to your heart, it's the first impulse ... which surely means it's closest to the invisible poem that you’re trying to write. I think the poem is invisible as you begin, but in a different sense – invisible because it’s not written! (laughs) I’m not saying that the first draft should be the final draft by any means, just that it should be respected.

And it’s a funny thing, the poem at the end of my book, 'Red Angel', was actually a long poem that started off about a friend of mine and was based on a dream – and then it wandered off. And once I let it wander and cut it off from my original dream, that poem then found itself. It just formed, it cohered, it arrived. And I thought, well this is a sonnet. And once I put it into a sonnet form it changed again. For me, it sometimes seems as if it’s something that's there … complete, I find it arrives like that. When I'm half asleep and the poem is there, it doesn't need much....

Another of my books on writing is by Richard Hugo, called The Triggering Town, subtitled Lectures and essays on poetry and writing. The basic tenet of the book is that the writer begins a story about their town, and it ends up being about quite a different town altogether – the first town gets left behind, and probably gets left out, like the first bit of my poem 'Red Angel' which was discarded. Nevertheless, without the initial thing you discard, you wouldn’t have the final poem.

Another of my books on writing is by Richard Hugo, called The Triggering Town, subtitled Lectures and essays on poetry and writing. The basic tenet of the book is that the writer begins a story about their town, and it ends up being about quite a different town altogether – the first town gets left behind, and probably gets left out, like the first bit of my poem 'Red Angel' which was discarded. Nevertheless, without the initial thing you discard, you wouldn’t have the final poem.

I once went to a workshop, run by Mark Doty, the American poet. It was a large group but he allowed each person to tell the group the one single thing that they battled with most in their poetry. Now the group was an interesting collection of people, some were prestigious writers who were editors of journals, others were managers of publishing houses, etc. It was interesting to hear everybody’s particular personal battle. And the question I aired with that group was, what to do with a lot of remnants – small poems – because it’s not always a good idea to cobble things together; and he said, stay with that piece of writing longer, and go deeper. Don't write necessarily longer, but deeper. Which is like a different dimension, it's not like the Triggering town idea of travelling to a different area, it's dwelling within the poem and going deeper into it. That’s when I think the poem starts to tell you what it means. This is why I write so slowly maybe....

I think that’s very important, because otherwise we can be didactic. That’s poisonous for poetry.

Now back to my library…. I’ve a tiny collection of books on opera. I grew up with opera, thanks to my mother. I became very interested in the art of the libretto recently, thanks to Willem Bruls in the Netherlands,and I’ve collected some books about writing libretti.

I’ve a complete set of Famous Reporter, and various issues of Island. and HEAT. And I can’t get rid of Scripsi, I’ve a few copies of it as well. And The Paris Review from long ago....

And these are what I learn from, what I teach myself; I find my work grows in silence, or solitude rather.

I've learnt a lot too. Thank you Anne, lovely to chat....

Kellas’ fourth collection Ways to Say Goodbye reverberates with themes of grief and its legacies within the various contexts of a world disrupted by climate change and social upheaval. The poems take the reader through dream sequences, abstract, ekphrastic and imagistic poems as well as deeply personal poems of loss. The effect is a cumulative building of a quiet world of reflective resilience as the poet tries out possible ways to do what is almost impossible – to love and to say goodbye.