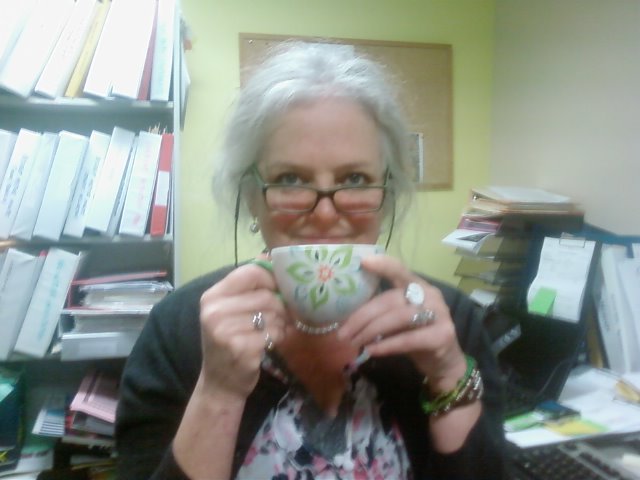

Philomena van Rijswijk is a poet, novelist and story writer living in Tasmania. Her most well-known novel, The World as a Clockface, was published by Penguin. Her poems and short stories have been published in collections and literary journals in Australia, Ireland and India. Her work was included in Best Australian Stories 2002 (Black Inc) and Best Australian Poetry 2005 (UQP). Some of her stories have been translated into Hindi and published in Indian literary journals and anthologies. Her poetry collection, Bread of the Lost, was published by Walleah Press in December 2013. Her latest fabulist novel, The Bishop, the Gypsy and the Dancing Bear, addresses the themes of xenophobia and border security.

When I ask Philomena what makes her laugh, she says she should maybe tell me first what doesn’t make her laugh!

“I don’t have a scatological sense of humour. I have had a Dutch husband and a close German friend, and it is a bit of a drawback if you don’t find farts etc. intrinsically funny. I think being turned off by the scatological is an Irish trait. I don’t laugh at the predictable (so that rules out most stand-up comedians, who get laughs from people who merely want to show that they have understood the joke - it’s a communal sniffing at each other thing). I don’t laugh at American movies featuring black men dressed as enormously fat black women or white men dressed as dowdy, old white women….

“All of the above types of humour, to me, are the product of neurosis. I like humour that reflects on the silliness of humanity and life in general, like ‘Monty Python, Little Britain, The Mighty Boosh’. I love that clever English show, “Would I lie to you?” I heard, once, that the difference between American and English humour is that American humour reinforces stereotypes, and English humour contradicts them. I don’t find much Australian humour very funny at all. Australians laugh at themselves while they are telling you their jokes. It’s very off-putting. There is also something very tragic about Australian humour eg. ‘Muriel’s Wedding’ and ‘Priscilla Queen of the Desert’ were tragedies, to me, not comedies. One of my very favourite English comedy skits is the Russian Babysitter skit from ‘Little Britain’. It makes me laugh every single time!”

What upsets Philomena? Ignorant bigots making stupid remarks on Facebook; “tailgaters and fast drivers, especially the ones with ‘Baby on Board’ signs, and people in four-wheel-drives taking up more than their fair share of the road. Michelle Bridges and ‘The Biggest Loser’ gets me upset, since I don’t like to see people ritually and publicly debased and humiliated. Staff rooms full of people on their mobile phones; mothers on their mobile phones, instead of interacting with their kids. Dog-owners who use their dogs to express the territoriality and aggression they are not able to express for themselves. People who talk to children and old people in baby voices. Please tell me when to stop … I’m on a roll…. ’A Current Affair’ makes me very upset, and so does that TV announcer who makes everything sound either smutty or sensationalist. You know the one I mean!”

Have there been particular periods of history that interested and fascinated you enough to have thought, I’d have liked to live through those times?

“I guess it sounds a bit uninteresting, but the times that most fascinate me are very personal, and related to the history of my family. Before I was born, my parents lived at Quakers Hill, which was even more west, and more remote, than Blacktown, where I grew up. I always heard stories about Quakers Hill, and it pained me, knowing that I would never see it or know it. Since we didn’t ever have a car when I was a kid, places like that may as well have been the moon, as the suburb next-door. I never did see where my family lived, and, when I say it pained me, it was a physical pain for a time. So, what I did was write a story about it, and that story was The Miracle Calendar, which was online as a podcast for a while, though I’m not sure if it still is.

“When I was two, my parents took us to a place called Ettalong for a holiday at a place I knew as Aunty Rose’s House. I never really knew who Aunty Rose was, but the memory of the house has haunted me for the past several decades, and that is because it was one of the few places I remember where we were a happy family. My brother was a new baby, and Mum and Dad pushed two club chairs together to make a bed for him. I remember the latch on the flyscreen door, the row of painted rocks along somebody’s driveway, and being pushed in the blue stroller by my father to the corner shop to get a block of ice for the ice-chest. I always kept the memory of that house as my idea of the perfect home, and I do believe I bought my present home on the basis of its similarity to that place.

“So, I guess what I’m saying is that the time I am most fascinated by is the tantalizing time where memories originate. It is not really a time at all, nor is it a place. It’s closer to imagination.”

Looking back to your teenage years…. What qualities did you seek in a friend, other than perhaps the ability to swallow a dictionary :)

“Swallow a dictionary? That makes me laugh, I don’t know if my vocabulary was anything special at that age (let’s say thirteen…). I was a bit of a flake, but the nuns, apparently, saw some potential in me. Sr Sheila Mary invited me to help her with the school paper, and Sr Roberta, my class teacher, decided, when I was in 4th form (Grade 10) that I should stay back in the library until five every afternoon, rather than go home to an empty house and play the guitar. Our library was tiny, and was run by an elderly refugee couple from Soviet Russia, Mr and Mrs Klotz. So, for a year, I had a library full of fantastic literature all to myself for an hour and a half every day. I wrote my first poem there.

“My friends were bemused by me. They would get frustrated with me, and said that I had no opinions on anything, because I would say: Well that is them, and I am me, so I can’t say what is right for them…I guess I was a kind of existentialist, and I did read The Outsider, amongst other things.

“My best friend was not a spock, but a sporty girl. She came from a big, rough and tumble family, which was a great antidote to my own isolated and introverted family.

“What attracted me then was what attracts me now, in finding friends, and that is a kind of intensity. I was friends with a German girl called Hildegarde who had a lazy eye (the nasty girls called her Half Eye). I once, in a downpour, got off the bus at her stop instead of mine and we climbed into the house through the window, even though she had a key, and we put a waltz record on and danced around the house in her mother’s exotic underwear. When we were about fifteen, my best friend and I were determined to be hippies, so we went to the hippie shop (Costless Imports), and bought Indian thongs and incense, thinking we could, maybe, smoke the incense. We were very innocent.

“I have always been a mixture of a loner and people-person, which is a bit of a conflict, socially speaking. When I was fifteen, I fell madly in love with my English teacher. She had been a nun, but gave it up when she was in a bad car accident. That was my first passion, and she used to call me The Professor. She was the first teacher who didn’t think I was partially retarded.”

So access to a good library from an early age drew you to writing…. And these days you’re fully immersed in family, reading, writing and work … what you do when you find time to relax?

“Oh, to relax…. To relax I play nice Indian music, I do yoga, I sit in the sun, read, do the weekly crossword, go on Pinterest or just surf the ‘net, light candles and incense, ring my kids…I nearly forgot…I paint. I play guitar and I’ve bought myself a bodran. I garden (my garden is pretty wild). I drink non-alcoholic beer with my friend. I read, of course, and write. I watch old black and white movies in bed on my laptop. It’s all very simple. I actually struggle to relax. I’m happy when I have structure in my day. Blame it on Mum and the nuns.”

Well I’ve listened to bodran playing…. Mostly on youtube, invariably it’s accompanied by tap dancing. Do you tap?

“I can’t tap dance, but clogging appeals to me. Apparently, that’s where tap dance originated. It’s interesting, how different cultures focus on different parts of the body in their dances. Like the Irish with their arms stock still and their feet going like crazy. With belly dancing, it’s the pull down to the earth, the centre of gravity. There is a stillness that surrounds the belly movements. I enjoyed the folkloric style of belly dance, as opposed to “cabaret”, which was an import to the middle-east from Hollywood.”

And you’re taken with black and white films…. You’ve never watched the 1939 film ‘Ninotchka’, by any chance? I came across it at a film festival many years ago and have been a Garbo fan ever since….

“No, I haven’t watched ‘Ninotchka’. The film I most recently watched was M.R. James, ‘Whistle for Me and I’ll Come’. It was based on a short story.

“One of my very favourite movies, though not black and white, is Tarkovsky’s ‘Nostalghia’. I love the beginning of the film. There is this plaintive voice singing a folk song, and a family walking down a hill into the mist, and an Alsatian dog. There’s just something about it that moves me. It’s almost like a memory. I have watched so many films, that I forget many of them. There is another one that I love, about a Siberian hunter called ‘Dersu Uzala’. It is more than a film. It’s a journey. Oh, I could go on about films for a week.”

Well, there are few film references in your 2013 poetry collection Bread of the Lost other than the poem ‘From Here to Eternity’, but plenty in the way of artistic and cultural references … Degas, Odysseus, Baba Yaga, Souad Massi and Ghir Enta, et al. How would you describe Bread of the Lost, which - to me - reads as an elegy of sorrow for love lost?

Bread of the Lost is a very personal collection. Some poets say that they try not to put the personal into their poems, but I don’t believe that’s possible, even if your poetry consists of numbers and symbols. I think you can either be transparent about the personal nature of your poems, or try to disguise it. The poems in my collection are held together by a sense of the erotic that imbues the natural world and human experience. When I talk about eros, I don’t mean sex. What I mean is the generative energy that is at the core of existence. My little poem, 'Cub', expresses this notion:

This day-/I eat it up;/ these birds- I drink their squeaking wheels; /this soft grey velvet hour-I lick it up;/this nacre moment-I press it to my breasts;/this time born fresh and squawking- I hold it wet/ to my mother heart./This now, this eros, this little god-thing-/I let it at my breast to feed like a cub.

“(I actually don’t like reading quotes broken up with slashes, so forgive me!) I think my mothering-ness informs my poems. Even in the way I feel about the old people I work with comes from my mother-soul. I mean “mother” in the way Rilke used it, when he said that men can also be mothers when they create.

“Of course, there is a lot in my poems that is intimate. The reason I collected those poems together was because I was tired of the nihilistic poetry I’d written when I was stuck and unhappy and depressed. I decided to write and put together poems that were life-affirming. The period of my life during which I wrote them was a kind of rising from the ashes.”

Last winter, snow fell in Hobart and on beaches out your way – I remember that memorable photo in the papers of a young surfer treading the beach in the snow, about to take her board out for a surf - and it reminded me of your poem ‘Remember when it Snowed’, which begins

Remember when it snowed?

Oh, remember when it snowed!

You went, blinded, with him,

alone into the snow.

It seemed there was no one else

in that white, enfolding world,

although those blurred faces passed you

on the road.

and while it’s ostensibly a poem recalling being caught in a snow storm, I’m guessing it’s about much more than that?

“Oh, indeed it is! When I sent the manuscript of Bread of the Lost to Edith Speers for a comment, she wrote back: A daemon has scruffed you by the neck and made you do its bidding, dance to its tune, until you are a veritable whirling dervish of poetic expression.

“Edith was right about the daemon. The collection was the result of something like a possession. I had no choice about whether or not I wrote the poems. One blogger suggested that I did not baulk at mining my most private experiences for my poems. She did not say it as though it was a bad thing, but I have experienced some embarrassed silences in response to the collection. One elderly poetry fan complained that there was ‘too much sex’ in my book. I explained that it was not sex in my book, it was eros. Working with old people for much of my life, I know that we never grow too old to for eros.

“The poem you quoted is about emotional detachment. The snow-storm and the emptiness of the road mirror a pathological kind of detachment. Most of us understand that it is a violation, in the situation where one is touched but that touch is uninvited and unwanted. However, this poem is about the opposite. It is about a case of not being touched, and of another kind of emotional violation entirely. It is about the aridity of emotional withdrawal.”

Envious elderly complaints aside…. You mention having worked with the elderly for much of your life - which includes working with the dying, no doubt. Is there a particular form of humour that emerges from that experience, as a means of coping?

“Really, there is not a lot of humour in working with people who are dying, though there is some. All in all, the people I work with are unbelievably kind, and they are often too worn out for humour. But they are incredibly patient and loving. There is some humour in working with people with dementia. You would go crazy, if you couldn’t sometimes see the funny side. But it’s a compassionate kind of humour that recognises the us in them. For example, one day, I went into a dementia unit and a lady who was standing at her doorway said to me: Hello! Have you come about the room? As you can see, this is the bedroom, and, here, you’ll see there is an ensuite…. and she proceeded to show me around her room, as though I was a potential tenant.”

Your poem ‘Crazy-angel-man’ has introduced me to the music of Souad Massi

Some stranger plucks at an oud

while Souad Massi’s mournfulness keens and croons

from the corner of my winter room.

… and I thank you for that. I imagine your musical interests are varied?

“Quite varied. I can, mostly, trace my musical loves back to their origins. For example, I sent Souad Massi’s song, Ghir Enta (‘Only you’) to a refugee Kurd that I met through Facebook. Souad Massi is an Algerian songwriter. The Kurd and I fell in love in cyber space. He was a mythographer exiled in Amsterdam. When I sent him Ghir Enta, he responded with ‘Why are people trying to kill me with their beautiful songs?’

“My love of Hispanic music began through a Texan friend who introduced me to the Argentinian singer, Mercedes Sosa. When she sings the Misa Criolla (Ariel Ramirez), you can almost feel the weight of a wooden cross on your shoulders. I love Amina Alaoui, who is a Moroccan woman who interprets the music of Andalusia. I also play Ravi Shankar, Harry Manx (who blends blues, folk and Hindustani music, and invented his own instrument, which is a cross between a slide guitar and a sitar), and Saharan rock band Tinariwen.

“I listen to a lot of classical music. I wrote a whole novel playing Ravel’s 'Pavane for a Dead Princess', and I love Saint-Saens’ 'Aquarium' and Satie’s 'Gymnopedies'. I adore Allegri’s 'Miserere'. My Catholic upbringing meant that we learnt to sing the Latin Mass and hymns, and so on. I think I had a pretty good musical education, considering the fact that it wasn’t a posh school.”

And your cultural interests, do they extend to cuisine?

“Other cultures really interest me. I guess there are some for which I feel a great affinity, and those have changed, at different periods of my life. My interest is not so much intellectual, but visceral. I have times when I feel a different culture. That might sound flaky, but I guess it’s like with my writing, I would rather use intuition than information.

“My kids know me as a good curry cook. I really have no time for nouveau cuisine. I do watch My Kitchen Rules, when it comes on, and it seems that those people know how to follow recipes, but they don’t understand the processes involved in cooking. I am good at understanding how things cook. I don’t believe in eating food that is unrecognizable.

“I feel very uncomfortable with faddish, self-indulgent cooking. I think it is the result of excessive affluence, and affluence is the result of the oppression of others. When I worked at my last job, which was supported housing, I used to cook once a week, and people could buy a meal for $2. That was very rewarding, knowing that those people would have at least one decent meal a week.”

Australian poet Peter Steele, asked how people responded to his published essays and poetry, laughed and said it was like listening for the echo of a feather dropped in the Grand Canyon. How did you find the experience of having a novel published by Penguin, was it positive?

“Oh, should I be polite and humble, or should I tell the truth? Having my novel published by Penguin was not what I had hoped, although it gave me a certain street cred as a writer, which was actually very short-lived. I was lucky to have my novel published by Penguin, as the stars had aligned, and I have to acknowledge serendipity in Penguin even reading my novel. I was awarded a Regional Writers’ Fellowship at Varuna- it must have been in 2000. It was my second fellowship there, and I must say, my two stays at Varuna were probably the best things that ever happened to my writing “career” (I use inverted commas around career, as the journey has been more like hitchhiking through Queensland with a pet dingo, than the streamlined projection that that word implies). At Varuna, I met Anne Summers, and it was Anne who recommended to her publisher, Penguin, that they read my novel, completed only three days before it was requested by the executive publisher.

“I won’t bore you with the details. My editor and I were not a good fit, and, by the time the book was ready to go to print, we were barely speaking to each other. I did a round of radio interviews and was invited to speak at the Sydney Writers’ Festival the week after my novel came out, but none of the books were in the bookshops. When I questioned Penguin about the timing, it turned out that the woman in charge of my publicity had just gone off on maternity leave. The book barely touched the shelves in Tasmania, where it would, presumably, have sold more copies, as the novel was an allegory about Tasmania and the Antarctic.

“I guess I agree with the image of a feather dropped into the Grand Canyon. The novel made a flurry for a short time, but I find that I have now fallen off the map in terms of the literary community, though I do keep plodding along, having short stories and poems published. I’ve found that the literary community forgets you fairly quickly, unless you live the public lifestyle of a writer. It seems that it is, now, becoming more and more difficult to have your work read by agents or by publishers. I have given up on the idea that big publishers are the ultimate judges of literary worth. I think of them more as being like insurance companies. They put their money where the best bet is. They cannot give the seal-of-approval to anyone’s writing, as, like any other manufacturer, they produce the product that will appeal to the most consumers. That is why small, independent publishers are so important. I know that self-publishing/online publishing is on the increase, but I’m not convinced that it’s the way to go.

“Ironically, people who would otherwise probably aspire to thinking globally, acting locally, get caught up in the writing fantasy, and tend to lose their way. Small, independent publishers provide an antidote to the global publishing world. In the way of the olden-days publishers, they can actually nurture their writers (though, obviously, this may not always be the case). Wouldn’t it be nice, if small publishers could get together regularly to sell their produce, in the way that market gardeners now get together at local farmers’ markets? Or, if there could be a chain of bookshops, like IGA’s in Tasmania, through which independent/ small-press-published books could be sold exclusively?

“I suppose I have learned to get past much of the ego stuff that goes with the early years of being a writer. I do, sometimes, need confirmation, but I turn to my closest writing friends and my family for that. I have at least three unpublished novels mouldering away inside my computer. It’s possible that they will still be there when I, myself, am mouldering away, but I have come to acknowledge that being a writer is a lifelong lesson in humility, for some of us, at least. I also believe that that lesson, in the end, makes us better humans, and possibly, better writers.”

Have you been the recipient of arts grants for the writing or publication of your books? What did you make of the short-lived ‘National program for Excellence in the Arts’ (now rebadged and renamed, ‘Catalyst’) which, to me, seemed like a duplication of resources, having a second tier of government taking on responsibility for decision-making on arts funding.

“Of course, Arts funding has been a big influence in my life, both as a writer, and as a member of the general public. My first books were published through Arts Tasmania grants applied for by Esperance Press, and many other publications and opportunities that I’ve had have been through federal and state arts funding. I think it’s becoming more and more important for the government to fund the arts, since those bodies, such as publishers, who traditionally nurtured the arts and artists, are driven more and more by lowest-common-denominator consumerism. However, the notion of a ‘National Program for Excellence in the Arts’ does sound a bit Soviet. It conjures up the image of rows of grey-denim-clad artists with crew-cuts (yes, even the female artists) and onions in their pockets soldering together gloriously nationalistic sculptures on mile-long, parallel conveyor belts … or is that just me?

You mention you’ve written a third as yet unpublished novel ready for a publisher, addressing the themes of xenophobia and border security. I wanted to ask you about the use of language in the creation of political schisms … the examples George Lakoff (US cognitive linguist) offers are ‘homeland security’ not ‘repression’, ‘law and order’ not ‘denial of human rights’, ‘the chattering classes’ not ‘intellectuals’ … ? Is language often employed to deliberately create division, in your experience?

“This is the kind of language usage that George Orwell labelled Newspeak. It always amazes me how quickly the new lingo is generated and bandied around Parliament. I wonder if there is a big room full of troglodytes somewhere, making up clichés, oxymorons and tautologies for politicians. I remember those plastic rings that we got on the top of Wizz Fizz (sherbet) bags when we were kids. If you looked at the picture on the ring one way, you might see a stage coach being held up by the baddies, and if you looked from the other direction, you’d see a horse rearing up and a US Marshall raising his gun and shooting. Language plays tricks on us in the same way. It makes us uncomfortable to be unsure, so we are relieved to be handed simplistic idioms with which we can frame our opinions.

“I suppose what is really meant by the ’chattering classes’ is the luxury of being able to feel comfortable with the uncertainty in between the two extremes of certainty. The term, however, somehow implies that those who take part in the said chattering are self-indulgent, idle and flippant. The image that the term connotes is simian, or possibly avian. However, those who can suspend judgement and consider issues from various angles do use their intellects. That is where the idea of the Devil’s Advocate comes from. Belief systems that don’t allow for this are fundamentalist by nature, whether conservative or progressive. As Gerard Depardieu says to Andie MacDowell in the Peter Weir movie, 'Green Card' (1990): Äll of your ideas come from the same place! Life is paradoxical. So are people. If all your ideas fit together into a neat package, then, most likely, they are not your ideas, but the product of some ideology. Ideologies are not too intellectual, as they discount paradox, and neglect to reflect and question.”

Another point Lakoff makes is that what counts as a ‘rational argument’ is not the same for progressives as it is for conservatives….

“For the idealist, a rational argument goes beyond the immediate. The idealist thinks in ways that are fluid, and conceptual. The pragmatist thinks in concrete ways. The pragmatist’s type of rational argument is short-term focused. The idealist tends to look beyond the short-term. That’s because the pragmatist judges the worth of ideas by looking at probable concrete results. The results have to be short-term, or they are not concrete. The idealist, on the other hand, almost always considers the long-term, as short-term clutter gets in the way of his vision.

“Idealists often frustrate pragmatists, because they can be contradictory. They can be like the communists who wanted to liberate the working classes, but were happy to have downtrodden wives. Pragmatists frustrate idealists because they cynically use ideals to convince others of the rightness of their short-term focused opinions- for example, the Prime Minister referring to the tragedy for the wider world that might be brought about by opposition to Adani’s Carmichael coal mine in Queensland that he has his sights set on.

“I think we probably need both: we need idealists (progressives) who are not contradictory, and who exemplify their beliefs; and we need pragmatists (conservatives) who are not sanctimonious or cynical, and who acknowledge the concrete nature of their policies. We need pragmatists who can work within a framework of ideals, or values, and we need idealists who acknowledge the real ramifications of their policies and work with the pragmatists to put ideals into practice.

“I have no doubt that idealists have caused as much trouble in the world as pragmatists. The missionaries who decimated ancient cultures and communities were idealists; anti-abortion extremists are idealists, too. Pragmatists, or conservatives, also cause problems with their short-term, concrete focus. Consumerism is quintessentially pragmatic. Educating children to be factory fodder is pragmatic. I fear we are living in a time of terrible pragmatism, wherein even those institutions that are meant to ‘care for us’ tend to use the ideal of care cynically, for the short term gains of the pragmatist.

"I am an idealist, myself.”

What about language in the service of gender politics, the labelling of Senator Wong in parliament last year as 'shrill' and 'hysterical', for example?

“For some reason, we seem capable only of divisive dialogue. We are left or we are right; we are pro-industry or we are green; we are chauvinist or feminist…. Wedge politics, I assume, is about reinforcing this divisiveness. It would be nice to think that we were smart enough and sophisticated enough to explore the no-mans’-land between often simplistic extremes.

"Sexism is, of course, a particularly nasty form of divisiveness, as it easily appeals to anachronistic notions of a woman’s place in society. Describing Penny Wong as shrill, for example, is saying that her voice should not be heard in the public arena, as it is too female. Claiming that she is hysterical is saying that Penny, herself, should not be present in the public arena because she has a uterus. It should not be surprising that these types of comments are being voiced in our current political climate, since the regime of the Abbott government has been a reign of phallocentricism, the central motif of which has been a pair of unapologetic red speedos. And how amusing it was, that Prime Minister Abbott should describe the hijab as confronting, when, for months, every newspaper front page in Australia sported his almost three-dimensional image virtually leaping out of the page to remind us of his most essential qualifications as a politician."

Panashe Chigumadzi, a young South African woman, argues that much of the racism directed at Blacks in South Africa ‘was not recognised or articulated until we found the anti-racist vocabulary to name it’….

“I agree that vocabulary is powerful in allowing us to put thoughts together. Language must create pathways in our brains. If we don’t have the language for an idea, we can’t think it. I suppose there have been notable times in my life when language provided a liberation. When I was in my teens, I read a letter from a doctor that described my father’s mental illness as Paranoid Schizophrenia. I remember the legitimacy that those words lent to the suffering we had experienced living with a seriously detached and delusional parent. Until then, we had merely had my mother’s words for Dad’s sickness: he was “mad”, or “sick-in-the-head”. Language can somehow transform a private experience into a communal one, reassuring you that others have experienced the same things, and that your suffering is legitimate.

“Words are, obviously, very important to me, and it irks me when people are oblivious to nuances. There are prejudices and assumptions in the seemingly simplest of phrasings.”

Okay, let’s presume a negative response to the opinions you’ve just expressed. 'Bleeding heart material! Fine in theory, but....’

“Yes, I imagine I would be labelled a ‘lefty’ and a ‘bleeding heart’, though those two appellations are made without much depth of thought, whenever they are applied. They imply some kind of softness and unreality that only the “intellectual elite” can, supposedly, afford. Contrary to these assumptions, compassion and community-mindedness are survival traits. We make a big thing of survivors of various illnesses and crises, but the kind of survival we celebrate is simply the will to live. Real survival entails the ability to live communally, and it means being able to do all those things that mean communal survival.

“The human race has not survived for millennia because of individuals, but because of families and extended families…ergo: communities. Individualism will be the death knell of the human race. Compassion and social conscience come from a kind of strength and toughness that the self-interested cannot imagine. My siblings and I grew up in a two-bedroom house in Blacktown with a schizophrenic father and no real extended family. I have raised five kids on one small income, I have been marooned in various towns without transport, car or even phone. I have been a single parent. (When I became a single parent, I had $200 in my bank account). I have had clinical depression. Nothing has ever really been ‘handed to me’. I’ve worked with prisoners, homeless people, the dying, people with drug and alcohol dependence and with mental illnesses. It is my belief in inclusiveness and my adaptability that allows me to have compassion towards asylum seekers and other people who need our help.

"Those indulged, right-wing conservatives who sneer at bleeding hearts and do-gooders are like feet that have never been without shoes. They are soft and white, and absolutely useless when it comes to walking on hot coals or rough ground. Who is going to pay for us having compassion and a social conscience? I suggest the real question is this: Who is going to pay the price for not having them? It won’t be just the poor, displaced, brown people who will pay the price. It will be all of us… It will be our own children, and our own grandchildren."

Has Australia been attracting attention to itself politically for all the wrong reasons? The Adam Goodes debate, for instance….

“Yes, indeed. I have said for a while now that Australia is the new South Africa. I actually do believe that’s how we are seen by the rest of the world. Let’s face it: Australians have always been their own biggest fans. I have spoken to quite a few migrants, over the years, including post-WW2 and more recent ones, and they have all agreed that Australians are very needy. They want to be told that they have the most wonderful country in the world. They want people to believe all the propaganda about being sun-bronzed and laid back.

To my mind, Australians are very good at self-delusion. As they used to say, they are “a legend in their own minds”. I don’t exactly know when it was, for example, that we started recreating Australia Day. When I was a kid, it was merely a public holiday. No one really cared what it was for. Then we started talking about “the traditional Australia Day backyard cricket match”, the “traditional Australia Day barbecue” (I had never even had a barbecue until I was about fourteen) … even, according to one TV newsreader, “the traditional Australia Day Aboriginal dance”. All this sentimentality and self-delusion makes me nervous. I remember something that Robert Dessaix said about the most brutal societies being the most sentimental ones.

“And Australia is a brutal society. How else could we stand for the illegal detention and abuse (including rape, sexual abuse and torture) of asylum-seekers, including children and minors? How else could we condone the treatment of Aboriginal people? I think that’s how the rest of the world sees us. No longer does the image of the blond, blue-eyed and beach-going Australian wash (if, in fact, it ever did)… in the eyes of the world, we have managed to transmogrify into brutal, belligerent and bigoted. And no amount of tear-jerking backyard makeovers is going to absolve us, in the eyes of our grandchildren.

“Australia reminds me of the obnoxious adult who still thinks it is a cute kid. There is nothing more grotesque. For a couple of hundred years we have bumbled and stumbled around, patting ourselves on the back for our youth and vigour and lack of sophistication. It seems that the further removed from the unsophisticated and charming invented Australian we have become, the more we believe in it. Even the phony accents on modern movies set in the past irritate the be-Jesus out of me. If you look back at news footage right up until the fifties and sixties, Australians had English accents, not the nasal twang reinvented for the movies. Oh, don’t get me started!

“Recently, on a weekend trip to Manly, I said to my daughter that anyone who believed that the real Australian was blond and blue-eyed and English-speaking must live in a cardboard carton. Just in sheer numbers, the blond and blue-eyed Australian is a myth, and has been so probably since the gold rushes. In fact, I doubt that most of the convicts were blond and blue-eyed, coming mostly from across the Irish Sea.

“What I believe is this: that the rest of the world is getting quite nauseous, generally, over Australia’s racism towards its indigenous people and its treatment of asylum-seekers. I am old enough to remember South Africa under apartheid, and the boycotting of South Africa in sport. That was how the rest of the world showed its disapproval of South Africa’s treatment of its non-white population (even that term is obnoxious- like calling a woman a man without a penis, but what I mean is: it was not just the black population that was stigmatised, but also anyone who was not, basically, of Dutch or English descent). I think that the world should show its disapproval of Australia’s racism towards its First Nation people, and its unlawful treatment of asylum-seekers. Since so many people seem to think that “Australia is full!” I suggest that we expatriate a redneck for every asylum seeker that we take in.

“Specifically, about Adam Goodes … he has been like the canary sent down into the mine shaft to test for poisonous gases. What his war dance did was show that something definitely stinks at the bottom of Australian society. You know, the bigots call themselves the real Australians…they say they are the ones whose jobs are being taken by cheap labour from overseas, whose seats are being taken on trains etc etc. Let me tell you, I am as Australian as the next person. I was born and raised in Blacktown. I run a page on Facebook called Memories of Blacktown. It has been running for nearly three years and has a reach of 11,000 readers. In all the time it has been going, I have deleted two vaguely racist comments. They weren’t even all that offensive, but that is just my policy.

(By the way, the demographic of Blacktown is 2.7% Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, which is the largest urban Aboriginal population in NSW; 37.6% of Blacktownites were born overseas; the most common languages spoken, other than English, are Filipino/Tagalog, Hindi, Arabic, Punjabi and Samoan). I challenge any of those rednecks who call themselves Real Australians to be more “Australian” than someone who has spent their whole life in Blacktown. What has struck me about the people who have contributed to the Memories of Blacktown page is their old-fashioned decency. It is the bigots and rednecks, with their meanness of spirit and foulness of tongue, who are not the real Australians. They are as out-of-touch with real Australia as the over-privileged right-wing politicians pretending to lead this country.”

What did you make of criticism from some sections of the community, that his dance was inappropriate because it wasn’t traditional in the same sense as the haka performed by New Zealand’s rugby players?

“Oh, for heaven’s sake! Why does the dance have to be traditional? Goodes is an Aboriginal man. Ergo, his dance was an Aboriginal dance. That is the kind of attitude that would like to see Aboriginal culture locked up behind glass in an anthropological museum. Aboriginal people are living NOW. They have a living culture now. Comments like those imply that Maori culture is somehow superior to Aboriginal. There is only one way that I think Aboriginal culture could learn from Maori culture: they reputedly cooked and ate their commentators! It is a fine thing to completely destroy another culture, and then complain when the members of that culture, so cruelly ravaged, try to rebuild what they have lost."

It’s a been a year since the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris. During the same period of time, a number of Bangladeshi bloggers have been murdered, Mexican journalists executed and a reformist Mexican mayor murdered hours after taking up office. When you hear of these stories, do you despair for freedom of speech?

“I guess I despair for Truth, and journalism, and journalists, are often vehicles for truth. I guess I need not add the word always, as that, indeed, would be an exaggeration. I don’t understand how we can legislate Mandatory Reporting for suspected child abuse in one instance (in our “normal” lives), and absolute negligence and abuse in another sphere. Is this what George Orwell meant by Doublethink? We seem to be developing the ability to believe in conflicting ideas at the same time. For example, we are encouraged to believe that turning overloaded, leaky boats back at sea will save lives? I keep remembering the images of people jumping out of the windows of the World Trade Centre in 2011. Thinking that turning boats back will save lives is like denying help to the World Trade Centre jumpers, because doing so will just encourage others to jump. Asylum seekers have run out of other options, just like people jumping out of 110-storey towers.

“It makes me sick to think of the extremes to which this government, supposedly mandated by the Australian people, will go, and how close to the surface are amorality, brutality and xenophobia. Anyone who now gives evidence as to what lies below a thin veneer of democracy is at risk. Interestingly, we now live in a society in which our political opinions are volunteered for monitoring via social media. How easy we have made it for interested parties to keep us under intimate surveillance!

“Should freedom of speech be protected, as an 'ideal'? Can you protect a pure, unadulterated ideal, regardless of the way it is expressed? PEN says that we can, and that is why it believes it is appropriate to give awards in instances where they do not condone the actions involved, but celebrate the ideals behind them, for example, Pussy Riot, who removed their clothing in a Russian Orthodox church.

“Right now, the Australian government is protecting the ideal of national security through its border protection policies. The American people protect the ideal of defending themselves against an armed militia through their gun laws. The children of the Stolen Generation were taken from their families and communities for the ideal of assimilation into white society. Historically, it’s easy to see that there is no such thing as a pure ideal uncontaminated by its context. It is naïve to believe that you can support freedom of speech as an objective idea. What we call ideals are shaped by the zeitgeist and by its distribution of power.

“When PEN awarded Charlie Hebdo for its cartoons ridiculing the image of Mohammed, it condoned the offense given to all Muslims, and not just extremists. Were the Charlie Hebdo cartoons about freedom of speech, or freedom to desecrate? When the Taliban destroyed the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001, the rest of the world was up in arms. Since Islam forbids the depiction of Mohammed, then it would seem that going against the prohibition, especially in an irreverent manner, is a type of desecration of the 'unseen image' of Mohammed. PEN argues that the need to call attention to the barbarity shown by Muslim extremists justifies this desecration. Perhaps this is so. However, in doing so, I don’t believe the Charlie Hebdo cartoons were celebrating freedom of speech, but were picking up the gauntlet of religious war, and asserting the freedom to desecrate. Since I don’t believe in holy wars, or in desecration of other people’s sacred artefacts, then I can’t agree that the cartoons were acceptable, or that they actually did promote an ideal called freedom of speech."

Have we spoken yet of faith and religion? Let me ask you about another of your poems, ‘Time’s a Wild Thing’, in particular the lines

The whole world is the white corner-post of the porch,

a noble column, square, important, Protestant,

and half a dozen leaves

of a pagan cherry blossom tree

straining to brush it.

because I’m reminded of novelist and short story writer Geoffrey Dean's response to an interview question, some twenty years ago, as to whether religion had played much part in his life…. Not such a great deal he replied, before going on to reflect on how very much his grandmother - a strict Methodist - found sinful: even table legs. ‘Yes, table legs. If they had shape to them they had to be covered in case they were mistaken for human legs.’

On thinking of your words, ‘a noble column, square, important, Protestant’, I wonder whether your own sense of faith is similarly austere ... ?

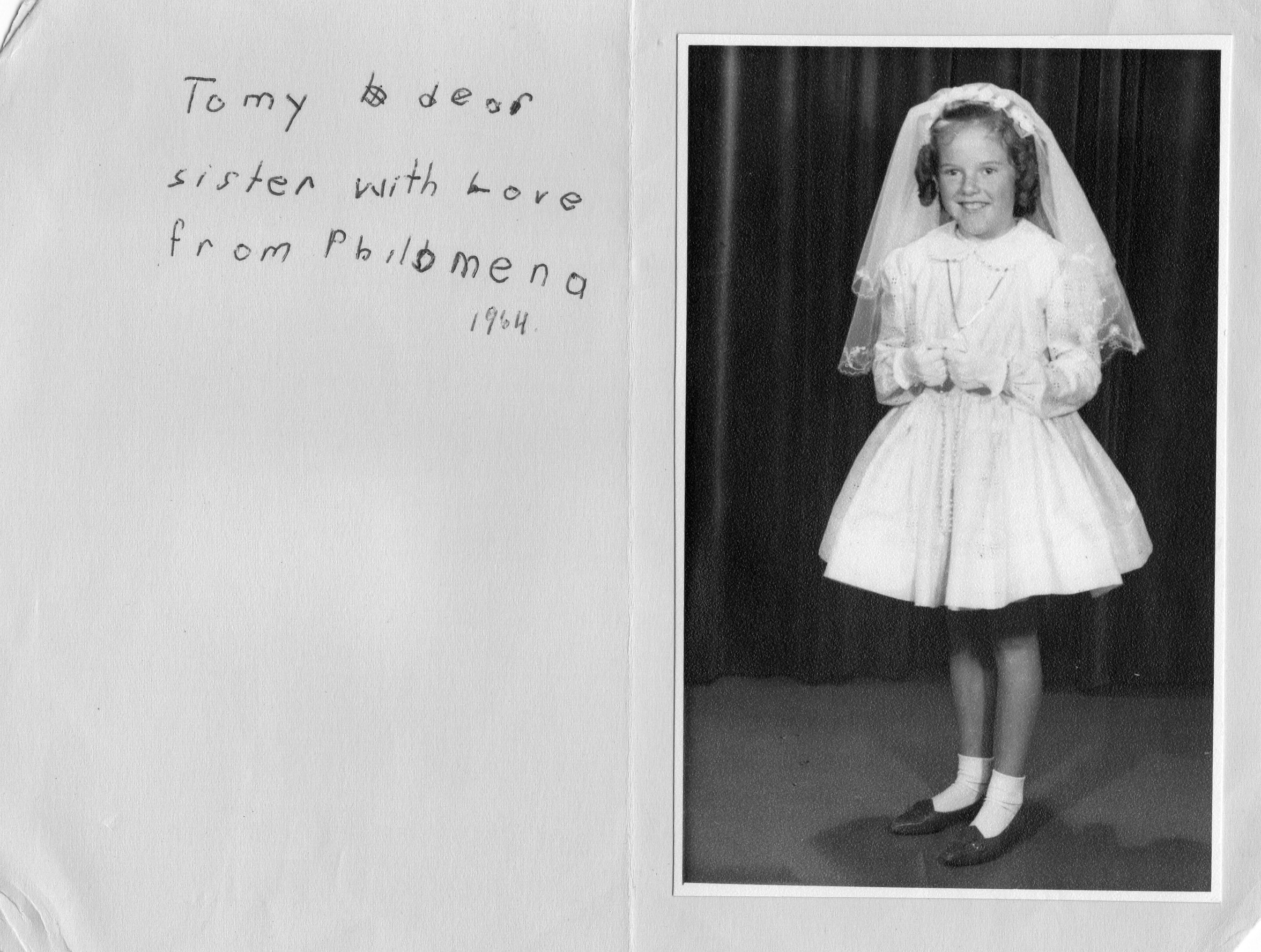

”Being brought up in a seriously Catholic family, and attending Catholic schools, have both been enormous influences on my writing. Most of my forebears were Irish, excluding my mother’s maternal grandparents, who were Prussian Lutherans who fled to Australia because of persecution. Growing up, our extended family consisted of eight Irish nuns, transplanted from County Cork to Australia as missionaries. Thus, even though we were third generation Australians, we grew up surrounded by Irish accents and a certain Celtic obliqueness.

“I think of Catholicism as my culture, rather than my religion, as I do not espouse the doctrines of the church, nor have I since I was about fifteen. I guess this is more comprehensible, when you think about Judaism. Even Jewish people who no longer practise their religion often carry on with the cultural traditions, music, language, foods, feasts and fasting they have inherited from their families. Catholicism is a language of symbolism. We grew up on symbolism, and also on a sense of the metaphysical. It is no accident that I gave my last poetry collection the title Bread of the Lost, as the symbol of bread was one that was ubiquitous in our religious education. There were bread, blood, fish, grain, water, ointment, vinegar, angels of death, rock, waves, manna…it seemed that the world was filled with elements that had layers of meaning to them.

“When I described the pillar holding up the veranda in Shoobridge Street as 'Protestant', I was referring to its upstanding conventionality, in comparison to the licentiousness of nature. When I was fifteen, our class teacher, Sr Roberta, carried a carton of books into our classroom, and asked us to choose one and read it in lieu of our religion class. I chose GK Chesterton’s 'Orthodoxy', and read it from cover to cover. I remember him saying that, if he had to choose a religion, he would choose orthodoxy, as it implied a complex history of art, music, tradition, symbolism, candles, incense, embroidered vestments: in other words, all the things about Catholicism that make the Protestant shiver with distaste.

“Protestantism puzzles me, because it is about convention and secularity. I was astonished, as a child, to visit an Anglican church to find flags and clocks around the walls. This still seems strange to me, as it implies that the Anglican church is a state church. There are so many paradoxes and inconsistencies in the Catholic church, but the colour and the complexity of symbolism are part of my make-up, and are very attractive to me. There is a certain brutality, too, that you can also see in my writing. It is a kind of ruthlessness about truth-telling, which Ruth Park talks about in Harp in the South. I don’t know if I can find the specific part, but, overall, Ruth’s description of the Irish family in her novels describes a very Catholic way of seeing the world.

“The symbols that I imbibed with my mother’s milk crop up again and again in my poetry and fiction. The notions of sacrifice, of sacrament, of cleansing…you could say that they are merely archetypes, but they are archetypes with little blue glass candle holders alight in front of them! My home is full of religious art, some of it Catholic, some of it Buddhist and some of it Hindu…After all, Orthodoxy is also an eastern religion, brought together under the Emperor Constantine. It is a distillation of some of the oldest civilizations of the east. I love its inscrutable oriental nature… (to paraphrase Adrian Mole’s dad).”

There’s a delightful interview with novelist Bernice Rubens in the 1989 publication Writers Revealed: Eight Contemporary Novelists Talk About Faith, Religion and God, that I’d like to quote from:

'I defy anyone to go to Israel and not be bothered by God. All those reminders of Moses and Abraham and Jesus and Mohammed. It can get on your nerves.'

'Do you find that frightening sometimes?'

'No, no. I am going to be interested to know how I am going to face my own death. I'm looking forward to that. I'm not looking forward to dying - I don't think a lot about that. When I do think about it, I look forward to dying just to see how I am going to cope with it, whether I am going to let God in, because I have been keeping him out for so long. I would be interested to know if I shall die a believer. Hopefully I shall die quickly and I won't have time.'

Does anything in what Rubens has to say resonate with you?

“What I think is that people believe in all sorts of things, and God is just one of them. Some believe in Science, and that is just a series of models for explaining how things behave. Bernice Rubens, apparently believes in Intelligence. I think you can just as easily believe in Intelligence, and thus avoid self-confrontation, as you can by believing in God. I have no concerns about people who believe in God. I only worry about people who don’t believe in people. Really, what people believe in, when they say that they believe in God, is so multifarious, that one word cannot really encapsulate all of them. You may as well use X as the word God. Yes, it’s a type of algebra where God equals X. God is the word for Unknown. People who claim to know what God is, therefore, miss the point. I think people have different comfort levels with conceptualizing. It is such a concrete word: God. I would prefer something more ethereal. The Hebrews used the symbol that we translate to Yahweh, but it was not actually a word at all. It was an in breath and an out breath. That idea makes more sense to me.

“In a moment of reverie, recently, I thought about how life is like a burning up. Just as the wood that I put into the fireplace combines with oxygen to make light, heat, and carbon, we also combine with oxygen over a lifetime, by eating and breathing. And aging is the process of us slowly burning up. I thought about this, and followed through with the analogy. The heat that we produce as we burn is what we call living. But what is the light? I decided that the light given off from our burning is what we call spirit. It’s not surprising that all cultures have some idea of spirit, and it is consistent with the natural world. It is consistent with the law of the conservation of energy. Every culture in the world has known that the stones around a fire are still warm long after the flames have gone out. They know that ripples spread out on the water’s surface long after the pebble has dropped to the bottom of the pool.”

Philomena van Rijswijk & Ralph Wessman. January, 2016.