CONVERSATION

Paddy Manning & Christine Milne

Christine Milne's launch of Paddy Manning's Inside The Greens

Fullers Bookshop, Hobart — 05th September, 2019

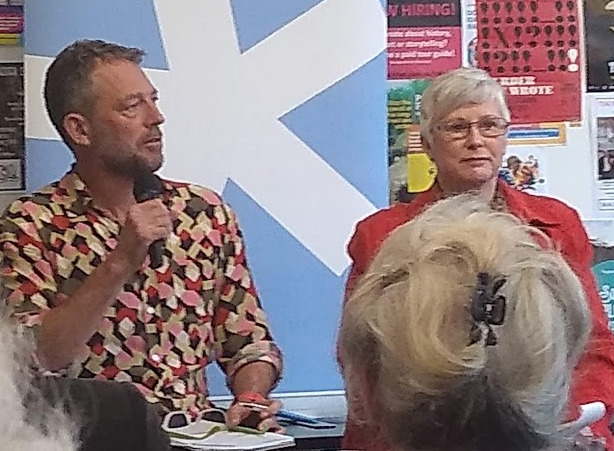

Christine Milne is seated beside Paddy Manning, the author of Inside the Greens: The Origins and Future of the Party,

the People and the Politics, (Black Inc.) She notes that it's something of a gathering of the

clans with so many Greens supporters

in attendance to hear Manning speak, but begins with a disclaimer. 'This is not an official history of

the Greens, nor was it something commissioned by the Greens. It's Paddy's take on the party and I’m really pleased that he went ahead and

wrote it because it’s disparate, complicated.... '

She refers to Manning's writing background, to the biographies Born to Rule, an unauthorised biography of Malcolm Turnbull, touted by

reviewer Paul Sheehan as 'a good biography. Scrupulous, fair and easy to read'; and Boganaire: The Rise and Fall of Nathan Tinkler,

the billionaire coal-mining magnate — as well as Manning's investigation into fracking in Australia, What’s Fracking? Milne's curious as to what's turned

his

attention to the Greens. 'Most of the media ignore

us. Why did you decide to write your analysis of the role of the Greens in

Australian politics, how long has it taken and what were the complications?'

Impetus for the book arose initially from a conversation with

activist and

academic Drew Hutton, Manning explains. Hutton, back in the eighties, had been a co-founder of the

Greens. With partner Libby Connors, he'd written A History of the Australian Environment Movement (published in 1999 by Cambridge University

Press), and was a founder (and in 2011, president) of the Lock The Gate Alliance, the

grass roots movement of farmers and environmentalists concerned at the impact of risky coal mining, coal seam gas and fracking. 'It was 2012.

I was researching the coal seam gas

book and driving from the western Darling Downs back to Brisbane with Drew, having been out interviewing farmers who

were dealing with coal seam gas walls popping up on their paddocks. During the course of the three hour drive

back to Brisbane, Drew spoke to me about Lock The Gate, how for him it was about the

biggest issue he’d been involved in — "as big as the Greens".

'Then he began telling me about

the internal

struggles of the Greens, a topic I found fascinating. That really started the thought process in my mind....'

A second moment came on completion of the Turnbull biography when Manning, sitting in ABC’s Ultimo

studio one day to promote the book, bumped into Bob Brown and his partner Paul. Brown was undergoing a promotional tour for his own book, Optimism.

He broached with Brown the idea of writing a book on the Greens — Bob's response was to give him the hurry-up. 'So I thought yeah, I’d better!'

'I embarked on a proper history of the party. It's

taken me three years to write and it’s certainly been the hardest thing I’ve ever done — involving archival

research of Bob’s papers, the United Tasmania Group papers, Dick Jones' papers, and others. And it's been a wonderful experience of what

I think's a great Australian story, the birth of this party and its career through state and federal parliament.'

Milne quizzes him over her concerns with the Australian media, why it's so uncritical of the stable majority government

mantra of the two party system. 'The Greens have been around for nearly fifty years yet the Australian media still regards us as interlopers in a

two party system who should just go and join the Labor Party if we want to make things better.'

She refers to recent comments by state

Labor leader

Rebecca White, vowing Tasmanian Labor would never make the 'mistake' of working with the Greens again. (Widely reported, White's comments

accused the Greens

of not seeking consensus. “They ridicule and talk down to anyone who doesn’t agree

with their view. They leave people behind. Working people. Our people. It was a mistake to think that Labor could ever work with the Greens.

We will never make that mistake again”).

'As if we haven’t heard that since Michael Field in the 1980’s, hello deja

vu!' Milne adds.

Pete Hay's observations of a couple of decades ago come to mind.

Look at Christine Milne and Michael Field. Christine will describe herself as a Whitlam-ite. She was inspired by Whitlam, he was a hero of hers, Whitlam was the person who set her off on her own personal political track. Talk to Michael Field and you get the same conversation. Yet you come to Tasmania and find Michael Field and Christine Milne are so far apart in ideological terms that never the twain shall meet.

'So Paddy, why is this happening? Is it because of a bias in the Australian media against the Greens? Is it essentially media

ownership,

as evidenced by the

Channel 9 fund raising

that we saw this week? Is it because the Australian media cannot see beyond a two party system,

that it doesn’t actually understand proportional representation in Europe and what goes on?'

'It's a complicated answer,' Manning replies, and compares the Greens with earlier minor Australian

political parties, the DLP (Democratic Labor Party, formed 1955 following a spplit from the Labor Party), and the Australian Democrats (formed 1977).

'It’s partly a misreading of the history of minor parties since the war. When the DLP launched,

they had a very rapid rise, then peaked and fell. A similar thing

happened with the Democrats — rapid rise, then a precipitous decline. It’s a very

different projectory the Greens have travelled — a slow build. Although their vote peaked nationally in 2010, it hasn't declined – it’s plateaued.

'It's a complicated answer,' Manning replies, and compares the Greens with earlier minor Australian

political parties, the DLP (Democratic Labor Party, formed 1955 following a spplit from the Labor Party), and the Australian Democrats (formed 1977).

'It’s partly a misreading of the history of minor parties since the war. When the DLP launched,

they had a very rapid rise, then peaked and fell. A similar thing

happened with the Democrats — rapid rise, then a precipitous decline. It’s a very

different projectory the Greens have travelled — a slow build. Although their vote peaked nationally in 2010, it hasn't declined – it’s plateaued.

'I think there’s a tendency for the press gallery to assume that,

like the DLP or the Democrats, the Greens are going to fade away. You hear it every

time there’s a major legislative decision or compromise, "this is the Greens’ Democrat moment, they’re

about to collapse". Firstly, the Democrats didn’t collapse. The Democrats went through a series of body blows — the GST,

Kernow’s defection, the tearing down of Natasha Stott–Despoja — it took years to kill the Democrats. And the Greens are much more successful

in terms of their presence in federal, state and local governments than the Democrats ever were. Both Upper and Lower Houses,

and councils. The Greens are a more formidable political party than any other in post-war Australian political history.'

'Then there’s the question about biases'. In Manning's view, many journalists are closet Greens. 'Though I’ve no evidence for it,' he adds.

'And I think

there’s a logical reason for this, it allows you to go hard at both major parties in your political coverage because you haven’t a

stake in either. But I suspect what happens is that a lot of journalists over-correct. Self-censor. They’re harder on

the Greens even though that may well be the party they vote for.'

'Yes; and it frustrates us year in, year out — decades in, decades out,' Milne responds heatedly.

* * *

Christine mentions the book's joint dedications, to Milo Dunphy and Jack Mundey. 'That’s an interesting combination, dedicated to the people there at the start.' She notes other important figures of the time — Judith Wright, Geoff Moseley, Vincent Serventy — before returning her attention to Mundey, the Sydney trade unionist elected secretary of the NSW Builders' Labourers Federation in 1968 and responsible for the Green Bans protecting inner Sydney heritage sites. 'Jack Mundey represented a shift in trade unionism by saying you could speak for the greater good at the same as you were speaking for the immediate concerns of the union. That’s something that unionism has tended to lose in recent years, but at that time they had the big picture. It was at the time that Jack Mundey adopted the term "Green Ban" relating, in Sydney, to the Rocks area, bringing together conservationists and unionists protecting the area, and it's where Petra Kelly got the name for the German Greens.'

* * *

Milne's curious as to Manning's view on

the emergence of the United Tasmania Group, formed in response to the decision by

the Hydro and the Tasmanian government of the day to flood Lake Pedder. 'Paddy, you say that moment has a singular place within

the history of the Greens so I wanted to ask you, what do you see as the role of the Pedder campaign and the Tasmanian

Greens in shaping the philosophical view and the modus operandi of the Australian Greens as a national party?'

Manning says perhaps the most profound thing he's read on the issue has been one of Richard Flanagan's essays in the book Flanagan edited

with Cassandra Pybus, The Rest of the world is watching. 'The point Richard makes is that in Tasmania, Labor — the establishment party —

had been in power

for thirty-five years, and the formation of the United Tasmania Group — because no party

was in favour of conservation of Lake Pedder — stamped on the Tasmanian party, not so much a hatred of Labor but a deep conviction

that Labor was not the answer. It was a rejection of

both parties, not just a decision that we will try and force Labor to be better, but a decision that Labor was not the way

forward, was not the solution and there had to be an entirely new party created. I dedicated the book to Milo because he played a very

important role in setting up the United Tasmania Group back in 1971, coming down and campaigning against

the flooding of Lake Pedder.

'The interesting thing about putting the firebrand communist unionist Jack

Mundey together with the true green, slightly conservative Milo Dunphy is to show that the tension between the hard left,

and your greens — your red-greens, your green-greens — has been there right from the very beginning. Both were

councillors on the Australian Conservation Foundation, but ended up being political rivals. That debate continues

inside the Greens today.'

Milne agrees. 'Yes, the UTG was a great moment of possibility of bringing together people from all walks of life and from all different political and

philosophical backgrounds to work on an environmental campaign. Interestingly, at the time of the UTG’s first vote, the core support

was much more heavily in the south than in the

north and in rural Tasmania. Pete Hay, our highly respected historian and political analyst, said at the time that "if green values have

little attraction to either the conspicuously affluent, or the traditional working class, the section of the community amenable to

conversion would seem to be fairly small". But when you think of the climate emergency getting worse, the Murray-Darling scandal, in spite of the

efforts the Greens have made in public housing,

public transport, public education, public health and Rachel Siewert’s tenacious campaign with the Australian Greens to get an increase in

Newstart — fifty years later we’re still

in the same position where we’re getting less than twenty percent of the vote. It goes back to Pete Hay’s position about the conspicuously

affluent and the traditional working class not voting Green then, and — largely — still not voting Green now. Why you think that is?

I'll also put to you Drew Hutton’s view, that the Greens

need a Bogan Revolution! Why aren’t we breaking through?'

'The media coverage of the party makes it harder,' Manning replies. 'But the best answer I heard to that question was that if you look

at the Greens’ vote in the suburbs, it's going

up. It’s just taking a long time, it’s not going to happen overnight.

I’m not convinced it's a ceiling permanently set that will stop the Greens at ten percent for ever. The Greens’ vote peaked nationally at —

what? — fifteen percent in 2010? In Germany right now, the Greens' primary vote is the highest vote of any party in the recent

European elections, so there’s certainly no ten percent ceiling there.

'Turning to Drew's idea of the Bogan Revolution, that you need to be able to get ordinary people turning up to a Greens’ party meeting —

not only innercity,

university-educated hipsters but ordinary people — well, they’re free and welcome to turn up to a meeting with inconvenient views.

I canvas the idea of Green battlers in the book, only because it’s so incongruous. You talk about a Green battler and you

think, "I’ve never met one of those!" But why? Why is that?'

Milne agrees there are a lot of green battlers in the bush. 'But they vote National!' She believes

rural people losing services, facing crises with water and climate, would be better off voting Green. 'Yet they vote for

people who don’t support them. That’s our reality.'

'One of the challenges Paddy identifies in the book,' Milne continues, 'is that the environment’s always been the absolute essential

pillar for the

Greens — alongside, of course, social

justice, participatory democracy, peace and non-violence — but the environment is absolutely at the heart of it. And yet we

now have what I would describe as "entrism"'. The depth of feeling is evident, because at the heart of Milne's 'entrism' is division.

'People are entering the party with a view to abandoning

environment as the central tenet of the Greens'. For Milne, one of the key issues facing the Greens is how to unite both arms — the members focussed on

social justice, and those on 'green' environmental issues — of the party.

* * *

Refocussing his attention from the future to the past, Manning suggests the Greens’ best legacy – state and federal – has been to try and clean

up politics. 'On improving the

workings of our parliament, on donations law reform, on freedom of information, on anti-corruption agencies, on electoral

reform, on a parliamentary budget office, on a whole range of things

like the federal ICAC — which will come — and have been argued most strongly by the Greens consistently for years. That’s a great legacy for a party, just by

itself. I think a majority of Australians want to see politics cleaned up and corruption and dirty money out of politics.'

Milne holds high a copy of Manning's book.

'On the back cover you ask "Will a refusal to compromise be a stumbling block for the Greens in the

future?" Now that’s reminiscent of Labor’s harping on that the Greens always make "the perfect the enemy of the good", that the

Greens won’t compromise: but it’s just not true. The Greens have compromised endlessly over time to get outcomes, and we can give

you any number of examples of that.

'But the Greens have bottom lines. We'll compromise, but we will compromise to a point and

then we will say, no, that infringes international law, or that just can’t be done. Surely that

is a position of policy integrity and political integrity ... yet we get criticised for it, because we’re not "pragmatic enough"

in order to sell everything out, in order to get a deal, in order to get an outcome. Why do people perpetuate the notion that the Greens won't compromise,

and to what extent in your book do you acknowledge the compromises we've made over the years?'

'We’ve accounts from Rudd, Gillard, Combet,

and Swan of the decision made in 2009 to vote against the emissions trading scheme,' Manning replies, 'which is where the idea of the "perfect being

the enemy of the good" really becomes crystalised. I think there are still a lot of people – Green voters and most particularly,

non-Green voters – who hold that against the Greens.

'I don’t have a verdict on whether that was the right

or the wrong thing to do,' Manning continues. 'What I do think is that there should be room in Australian politics for a party that argues a position

that is consistent with the climate science. How hard is it? If Labor won’t do that, then a party will be created to do that because

it’s an existential crisis and somebody needs to make the argument.

'I’ve come to the same position on Adani. Should the Greens

compromise on Adani? Well I’m sorry — and I think a majority of Australians take this view — I don’t want that mine to go ahead. If there’s no party —

even if the Greens collapsed tomorrow — I think Adani itself would justify the formation of a brand new

political party called The Stop Adani Party, because most Australians don’t want that mine to go ahead. It’s just like the Franklin, just like Pedder,

just like Jabiluka – there’s a large weight of opinion there, and I think there’s room for a party that is

uncompromising. I think Labor needs to get real about the platform that the Greens have developed — let’s face it:

half the Labor Party would like to have those positions themselves. The reason the

Greens are such a threat to Labor is because if they take Labor’s left wing, Labor will be the poorer for it. Certainly, on Labor’s

left, they don’t want to see the Greens swallow up their entire constituency. Labor seems to be

learning the wrong lessons from this election defeat and leaving more room for the Greens — going back towards coal, going back

towards tax cuts that favour the rich.... I think this is part of the reason why there may well be some upside for the Greens from

where they are now.'

Christine Milne points out that since the election, Richard Marles —

the new deputy leader of Labor — has apologised to the coal industry in Queensland for not being more supportive, not only supporting

Adani but the expansion of coal seam gas. 'And of course on refugees, it’s extremely difficult to stomach the hypocrisy of the last

week with Labor so strongly supporting the Sri Lankan family — and I think it’s good that they have – but: who opened Manus

and Nauru? And who is not talking about the rest of the people stuck on Manus and Nauru? It’s not just Sri Lankan families, it's a policy

position. But this goes back to the perfect being the enemy of the good. It's as if people fail to recognise

that there is international law. The Greens have always made a point of saying, we will adhere to international law, that has to be

a bottom line — otherwise, if you’re going to go across that, where does that end?

* * *

'We’re just about to run out of time Paddy, but I wanted to read your conclusion to the book, which is a real compliment to the Greens,

‘By dint of idealism rather than opportunism, and hard work not money, the Greens have carried their place in parliaments and councils across Australia and love them or hate them, the country’s democracy is healthier for it’.

'I wonder, what is your overall prediction for the Greens for the future? Where do you think things are going to go in the next few years

for us?

'I’ll just speak to the hate bit (love 'em or hate them) there,' Manning replies, 'because I think the Greens have cultural problems that have absolutely crippled

the party in the two largest branches, in NSW and Victoria.'

He's referring to controversies in NSW (in one instance,

an upper house preselection ballot), and in Victoria where former

Greens Alex Bhathal quit the party over

'organisational bullying'. Manning mentions the latter fracas in his book.

On a blunt assessment, Bhathal was a high-profile victim of a long-running feud between two Melbourne branches, the Darebin and Moreland Greens. Hardly anyone knows whence it started, or what it’s about.

'So when I say love ’em or hate them, I mean it,' he continues. 'I spent so much

time reading toxic facebook posts of people attacking each other that it’s

a lifetime overdose for me. I think the Greens have problems in all states — NSW gets picked on, and NSW has been through an

atrocious last twelve to eighteen months. But so has Victoria.

'I think there’s a real threshold issue for the Greens to

address, there is so much being spilled. It's partly a disruptive political cycle — and social media —

creating a culture that’s not very healthy at the best of times, inside or outside the Greens. Also, I think the Greens have a

consensus-based decision–making process that is no longer working. It aspires to achieve a consensus which is impossible to deal with when you’ve

deeply entrenched factions, yet the system won’t allow you to recognise those factions.

'As part

of its maturity, I think the party needs to recognise that those differences, whether they’re person-, or policy-based; perhaps through an approach

like the German Greens

with their fundamentalist and pragmatic wings. I don’t have the answers. But I think the Greens will be crippled if

they can’t address that internal

cultural problem. People will turn off — or they’ll just never join in the first place.

'Yet what we saw in the recent federal election was that despite twelve

to eighteen months of disastrous infighting in the two biggest states, the Greens held the line. They had to defend, they couldn’t

go forward: in terms of representation in the senate, they had to defend a senator in each state — and they got re-elected, every

single one of them.

'And there are good reasons why those senators were re-elected. Certainly, if the Greens get the same vote in the 2022 election, they’re looking at eleven or twelve senators and, potentially, at

the balance of power in the senate in their own right. And then it won’t matter how many

times Labor says never ever ever ever ever.... There is an argument that if the Greens can fix their internal cultural problems and stop fighting

each other, that they might actually be able to take a leap forward at the next federal election.'

Christine Milne agrees internal challenges face the Greens. 'I always said when I was leader, you’ve energy to fight everyone out the front if the people behind you are with you. If however you’re trying to fight

everyone out the front and you’re not supported or there’s a big internal brawl behind you, it is just exhausting and it takes

away from your capacity to be effective.

'But like Paddy, I think the future is very "green" for us.'

Audience question

I want to go back to the 'winner takes all, you've got to have a majority government' question. We don't seem to be able to be sophisticated enough in this state — or in Australia — to embrace the European situation where no party gets a majority and it's actually a good idea to negotiate with each other, come out with accommodations and work from that. Can we ever move past that in Australia? What happens if and when the Greens vote actually improves, what does that mean for political outcomes? Does it leave the Greens always as the party that can moderate the worst of what some other party was about to do, and 'occasionally' get something up, but never implement their own agenda? Will there be situations where the Greens can get more of their platform up by being able to have this sort of sophisticated negotiation and attitude? Or is it not just the big parties but the media who are actually going to prevent that happening? And does that mean that the Greens need to actually try and work to become a major party, and take government in their own right? We never talk about that. Every time we get near to increasing our vote we think we're going to go into the balance of power. What if we didn't? What if we tried to go that next step ... is that even feasible?

The question of the Greens governing in their own right has perhaps been addressed, in Manning's mind at least, by his reference to

solving the Greens' internal problems as a prelude to the next 'leap forward'. His reply focusses firmly

on the possibility of a Labor / Greens coalition.

'I think in Tassie and the ACT — and federally during the Gillard years — you've examples of effective coalitions being formed between

Labor and the Greens. Even, for a short period of time, a de facto relationship with the Liberals in the Rundle era. Basically, I hope there's a

possibility Labor and the Greens could come to terms. And I'm not the only commentator suggesting this, Greg Jericho in The Guardian

was saying, after the election,

Labor and the Greens need to work together.'

Manning contemplates the prospect of an Albanese-led Labor Party taking the party back towards the right, perhaps resulting in a stronger Greens

representation in

parliament, thus presenting a greater likelihood of Labor and the Greens cutting a deal together. He says he's all in favour of a politics offering compromise,

but adds realistically, 'When you actually start talking to people about proportional representation most people's eyes glaze over.

Constitutional reform in

Australia is so hard that it feels like a pipe dream to talk about it. But gradually voters, by continually lowering that share of the

vote going to the major parties, will force coalitions onto the federal parliament. That trend has not changed — it's been going on for decades,

and it's a trend for which there's no sign of a reversal.'

Ralph Wessman, December 2019