It's February 2018, a fine late-summer's day. Throughout the morning, poets Nathan Curnow and Jane Williams present poetry workshops to a hundred and fifty attentive and appreciative thirteen and fourteen-year old students of a Victorian secondary college. The sessions culminate in a reading within the school's auditorium where Nathan and Jane are joined by poet and co-ordinator Brendan Ryan. Poems are shared, poetic forms interrogated, audience questions fielded.

(Left to right) Brendan Ryan, Jane Williams, Nathan Curnow

Now, hours later and with hands clasped firmly round a steaming cuppa, Nathan reflects on introducing poetry to teenagers. 'You need to target your audience,' he says, 'it's important to talk about things on their level, you've a responsibility to show kids that poetry is an option. It may not be a career but there'll be a few students in there today who might realise - yeah I've got skills like that, that's how I like to express myself. I look at Emilie Zoe Baker, a fantastic performer who's almost single-handedly raising the next generation of Australian poets through her work in Melbourne and across Australia, and I think: that's essential, that's a legacy right there. Emilie, Geoff Goodfellow, Sean M. Whelan.... we need those poets! We've got to keep telling and sharing stories. It's about carrying the torch, keeping it aflame.'

The counsel of a clutch of teenagers to pull him up when he gets it wrong is signally advantageous, one suspects. 'My daughters keep me up to date, I'd be hopelessly out of touch without them. They gave me advice on one of the poems I read today, said "Dad cut the Adventure Time reference, no one will get that, it's a show for younger kids!" And they were right. A lot of the time you make pragmatic decisions for different audiences, don't you? And hopefully you're versatile enough to be able to write it.'

The counsel of a clutch of teenagers to pull him up when he gets it wrong is signally advantageous, one suspects. 'My daughters keep me up to date, I'd be hopelessly out of touch without them. They gave me advice on one of the poems I read today, said "Dad cut the Adventure Time reference, no one will get that, it's a show for younger kids!" And they were right. A lot of the time you make pragmatic decisions for different audiences, don't you? And hopefully you're versatile enough to be able to write it.'

Working with children, especially within a workshop environment, is part and parcel of Nathan's career, as is writing for performance - although the latter remains something of a mixed blessing. Admittedly, performance poetry offers the gratification of immediate feedback but what's missing is the considered response to work on the page. 'Performance is entertaining - but surface to an extent, right? There's a role for entertainment and it's good to get people interested and excited about poetry, but on an artistic level it's no longer at the top of my list.' He admits to not enjoying being pinned down too much. 'Sometimes I feel other people have probably boxed me as a certain kind of poet. But I’m lucky - I’ve had room to change, for good or ill.'

Poetry ran a parallel path to scriptwriting throughout the early stages of his career.

'I've had support with my scriptwriting - a few readings of new plays - but nothing progressed from there. Doors didn’t keep opening, which was a shame. I probably wasn’t paying enough attention, hadn’t built connections within the theatre community. The idea was to work collaboratively with a director, usually on one of their ideas - whereas I was young and pig-headed enough to think I'll write whatever I want and throw that to a director and of course they will want to put it on, they will see the beauty and the genius of the idea and the dialogue.... ' He grins, lamenting his naivety, concedes it was never the case.

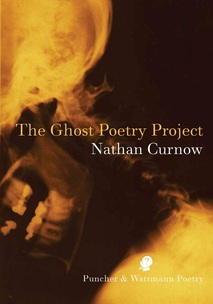

His first poetry collection was the Five Islands Press publication No Other Life But This, part of a 2006 New Poets series also featuring first books by Ali Jane Smith, Kate Waterhouse, Ross Gillett, Gita Mammen and Francesca Haig. Wider exposure arrived with the publication three years later of The Ghost Poetry Project (Puncher & Wattman), a thematic collection of poems written in haunted sites - from a gaol cell to a lunatic asylum to a night in a haunted hearse including the Old Adelaide Gaol, Fremantle Arts Centre, Port Arthur and Norfolk Island - lauded as 'a unique approach to the paranormal, melding historical accounts with personal experience.'

His perception at the time - still is - was of an Australia Council proclivity for awarding grants to thematic collections, and in terms of establishing himself The Ghost Poetry Project proved an ideal vehicle. 'It was a new idea, no one else had done it. At the same time, I think some within the poetry community baulked at the idea of capturing the imagination of a general readership – not that it did! - with something so gimmicky. Which - unashamedly! - it was.'

His first poetry collection was the Five Islands Press publication No Other Life But This, part of a 2006 New Poets series also featuring first books by Ali Jane Smith, Kate Waterhouse, Ross Gillett, Gita Mammen and Francesca Haig. Wider exposure arrived with the publication three years later of The Ghost Poetry Project (Puncher & Wattman), a thematic collection of poems written in haunted sites - from a gaol cell to a lunatic asylum to a night in a haunted hearse including the Old Adelaide Gaol, Fremantle Arts Centre, Port Arthur and Norfolk Island - lauded as 'a unique approach to the paranormal, melding historical accounts with personal experience.'

His perception at the time - still is - was of an Australia Council proclivity for awarding grants to thematic collections, and in terms of establishing himself The Ghost Poetry Project proved an ideal vehicle. 'It was a new idea, no one else had done it. At the same time, I think some within the poetry community baulked at the idea of capturing the imagination of a general readership – not that it did! - with something so gimmicky. Which - unashamedly! - it was.'

He says that work of a purely thematic nature no longer 'ticks all the boxes' to his satisfaction, and that for the first time in his career he's not working towards a new collection. 'I'm sitting back and writing whatever comes, taking a lot more time than I’m used to. Not worrying about direction or where it will be received.'

In June 2018, Curnow travelled to Europe with musician Geoffrey Williams to take part in readings in Germany and Poland. Beyond the immediate thrill of travelling and reading to new audiences, he hopes the exposure to outside influences will help broaden his appeciation of other traditions of writing. He's well acquainted with the work of internationally renowned poets such as Sharon Olds, WS Merwin, Ross Gay, Pablo Neruda, Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Bukowski, Emily Dickinson, Wallace Stevens - 'I know that list is North-America heavy' - but admits to not really knowing the great European writers. 'And you need to be refreshed by other voices, other ways of writing. That’s where the chain reactions happen, isn’t it? When they collide, when they move?'

In June 2018, Curnow travelled to Europe with musician Geoffrey Williams to take part in readings in Germany and Poland. Beyond the immediate thrill of travelling and reading to new audiences, he hopes the exposure to outside influences will help broaden his appeciation of other traditions of writing. He's well acquainted with the work of internationally renowned poets such as Sharon Olds, WS Merwin, Ross Gay, Pablo Neruda, Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Bukowski, Emily Dickinson, Wallace Stevens - 'I know that list is North-America heavy' - but admits to not really knowing the great European writers. 'And you need to be refreshed by other voices, other ways of writing. That’s where the chain reactions happen, isn’t it? When they collide, when they move?'

He's very familiar, on the other hand, with the writing of Australian poets 'because it was drilled in to me at uni - read Australian works! 'Adelaide poet Steve Brock once told me that all his heroes are dead. Thankfully mine are still alive,' he says, adding that his influences include Kevin Brophy - 'of course' - Ivy Alvarez, Judith Beveridge, Anthony Lawrence, Eleanor Jackson and Barry Hill who all have a way of speaking clearly, powerfully, memorably.

'I read Barry's Grass Hut Work (Shearsman Books) recently, a writer with an amazing poetic output - and I thought, "There's a master!"'

Other influences include the 'very fine' list of poets - Lorraine McGuigan, Ross Gillett, Ross Donlon and EA Gleeson - who make up his workshop group. They meet regularly, and it's to them he attributes the discipline of his writing routine. 'We come together and share our poems, so there's a form of impetus at work. The structure of those workshops has disciplined me to write regularly and we've done that for ... seven years? And once you get that discipline you can't drop it in a hurry, if ever; you remain alert, curious and interested in developing lines into poems. I'm working as hard and remain inspired as ever, and that's a blessing.'

'A blessing!' he repeats, catching himself by surprise. 'Here I am using religious terminology. I never use the word "blessing" '...

For a minister's son, a childhood focus on faith was inevitable. Very little remains these days, even less the need to write of it. 'In terms of what I personally need to access, to explore ... there's nothing. And I'm fine with that. It's been years since I turned away from faith and the church community, and as much as it brought me grief - it was huge! - I've moved on.'

'At least,' he adds with a grin, 'I hope so. We'll see with the next poem I write, maybe it'll all come out again.'

And possibly the political too? Because there's the rub.... Though decidedly political at heart (when the topic takes him, he'll tear off round the house engaging in a political rant with anyone who'll listen), he's never been entirely comfortable with introducing politics to his poetry (though he made a particular point of contributing to Writing to the Wire, edited by Dan Disney and Kit Kelen, on the asylum seekers in detention issue). Perhaps he's concerned not to appear polemical, perhaps he's wary of politically derived emotion as a driver to the detriment of form and structure....

Or perhaps he's edging towards a fork in the road ... ? Many poets have successfully fused the personal with the political - among Australians, Ken Bolton, Judith Wright, Oodgeroo Noonuccal, Graham Rowlands, Peter Minter, John Kinsella, Pam Brown and Tim Thorne to name a few. Curnow holds Thorne (instigator and for many years the director of the Tasmanian Poetry Festival) and his ouevre in high regard. Tim too once questioned the notion that poetry and politics might readily mix:

'When I first became politically involved I had already decided that poetry was the most compelling aspect of my life. That politics and poetry didn’t gel. And yet, there was always a nagging feeling that they should. For a long while I deliberately didn’t write poems that could be construed as having a political content.... But by the late sixties, early seventies I was starting to tie the personal and the political together. Whereas initially I’d thought I could separate the two, with a little honest analysis I realised I couldn’t - and shouldn’t – and so from then on I tried not to.' 1

'I haven't written many political poems,' Curnow admits. 'I've referred to contemporary topical issues in my performance poetry, trying to remain current to the younger generation and to the mood of the times, but I haven't done that so much in my page poetry. I'm wary of whether they stand up as solid poems. But I still have very strong politics, I'm actively engaged in the issues of the time and what's going on. Passionately!'

Passionate on one hand yet insular on the other? How does that work?

'Well every now and then, I get fed up and do something on the street. There was the time I painted a thirteen metre banner - 'Let Them Stay' - and rallied the Ballarat community to come and photoshoot it. Thankfully people turned up. But I instigated that off my own bat, it wasn't through an organisation, it was like: I'm a lone wolf, hey I've got this thirteen metre piece of calico in the shed, let's paint.'

'So I did. But the themes, the issues that I've given some of my life to haven't emerged in my poetry. Can't say it's something I'm completely happy with....'

'I come from an activist background - was arrested once - but walked away from that level of engagement to some degree. I studied Community Development for three years, an incredibly political course and by its completion I was jack of it, I just wanted to write. Being a father of four (always tired) and losing faith in activism - I saw fools on the Left, fools on the Right - I took myself out, made a conscious decision to walk away. I became a non-joiner, didn't sign up to anyone or anything. I thought, that's the best position for me to be in, observing and writing.'

'I think every writer feels isolation, don't they? You tend to be on the outside of things, it's your preferred position in the end.'

You sense he'd be a washout as a trade unionist.

'I don't completely trust unions,' Nathan confirms, before qualifying his words. 'I don't completely trust any institution.'

'I think it's because of my church upbringing. I back away pretty much any time things start to get organised, I'd rather not be involved but observing, being cheeky, saying, "Well why not this? Why not that? Let's not take ourselves so seriously." I found a lot of activists were just too serious, whereas I was about being creative and shaking things up in a different way. I've never quite fitted the mould; whenever I get a sense of the mould, I'm out of there. But that's the isolationist, the observer in me. You get a gist of it in my poem "All the Lines" that you published in an earlier issue of Communion about a cat on a windowsill - being able to see the outside world but lost to everyone inside because they don't know you're behind the curtains ... in that space where you're between worlds. That's inevitable for every writer, I think.'

Late afternoon is closing in. Nathan rinses his cup, readies himself to leave. It's a ninety kilometre drive to Ballarat. 'You were right about the reference to Adventure Time' I imagine him admitting on arriving home, settling contentedly again within the folds of family.

All the Lines

I sit between

the curtain and the cold of the window,

my tail wrapped around my base as neatly

as the cord of a kettle. Quietly I simmer,

listening within as I gaze upon the street.

It looks like I am guarding but I am

simply a presence and devoted to being one.

I have to remain though it is lonely at times

and confusing for the other cats. They call me

to fight and spray on things. My family believe

me lost. A window creature, made for the sill,

hidden and exposed. This ledge seems to fit

perfectly, so I remain as a kind of witness.

The sprinklers go up, the sprinklers go down.

It is hard to know what to make of it. Perhaps

it is a kind of territorial display—attack

the best defence. I sit here like a feature piece

but even action can be ornamental, the way

gnomes work late only to discover that

the garden looks the same each morning.

I wait and yearn, reading strangeness

strangely. A moth beats against the glass.

All the lines inside its paper wings

bidding on what light is.

1 From A conversation with Tim Thorne (2007)