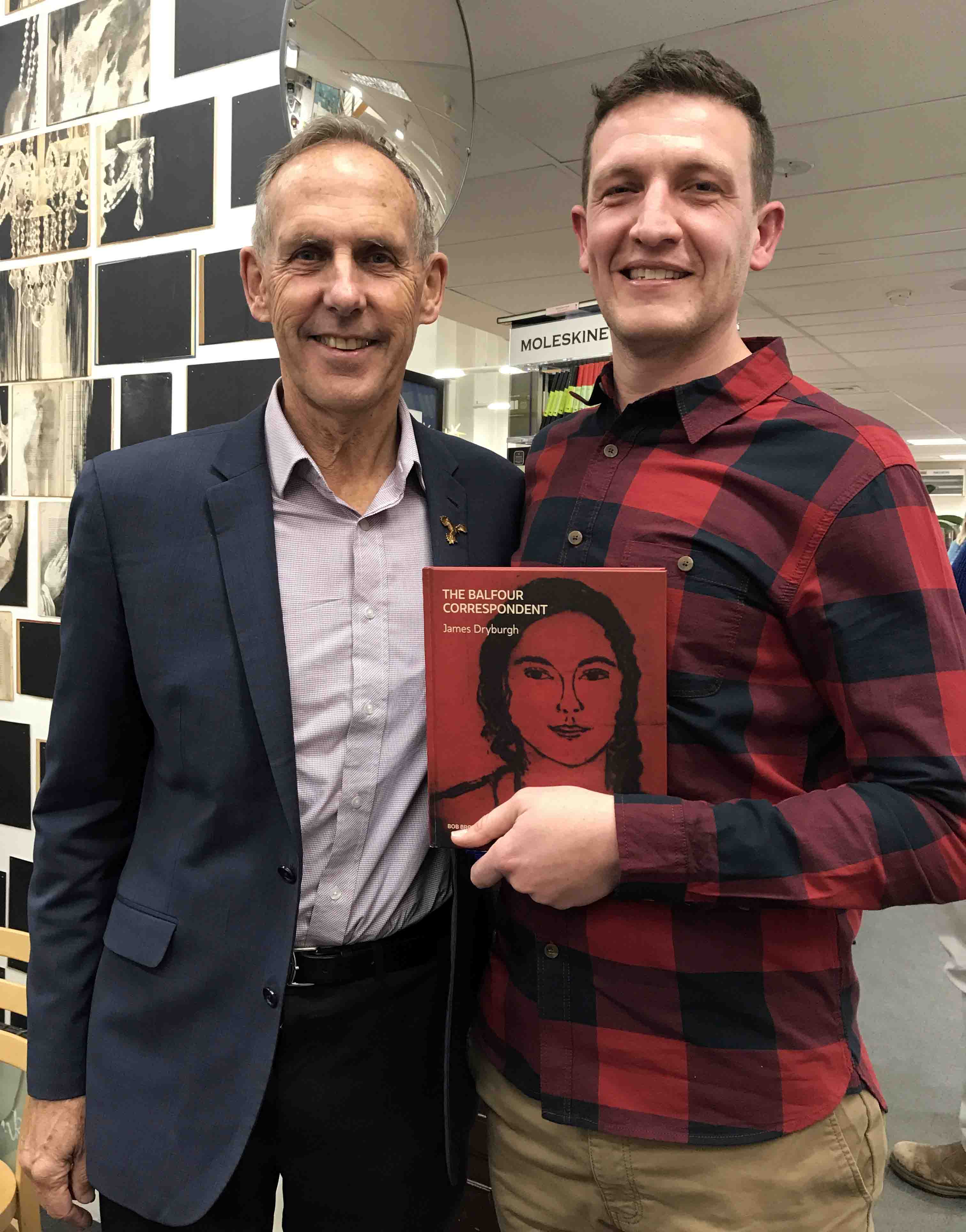

'THE BALFOUR CORRESPONDENT'

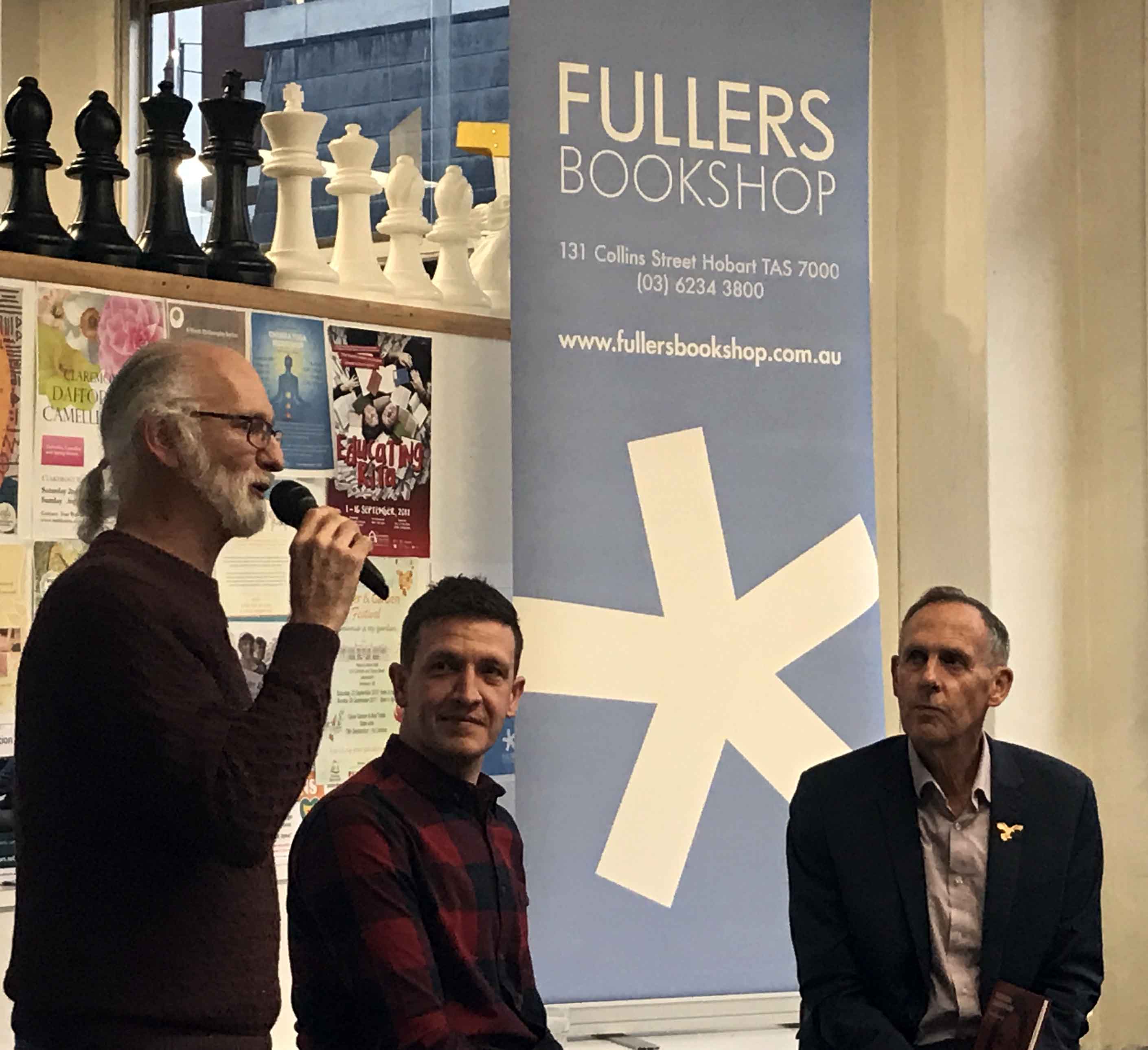

James Dryburgh & Bob Brown in conversation

Fullers Bookshop, Hobart - 30th August, 2017

Unbeknowns to me, Bob was sent an essay I'd written quite a while ago, and he thought it was a book – that's how it came about. This book is really due to the enthusiasm and vision of Bob and Paul. James Dryburgh

BOB BROWN

I'll start by asking James what on earth Silva rerum means.

JAMES DRYBURGH

It came into the book very late on, I hadn't drawn the connection till I dreamt it one night: Sylvia – silva. I knew 'silva' was Latin for forests, and the whole book is about forests, nature and this person called Sylvia.

I’d read a book by Ryszard Kapuściński some years ago, a Polish journalist. He’s a bit out there, fuses story with journalism to bring journalism to life a bit more; putting people into the situation of the subject rather than just offering cold reporting. He used a phrase silva rerum, the forest of things – used differently, but I guess it described his form of writing that merged reportage with story.

BB

And when you say, speaking to Sylvia in a letter - this fourteen or fifteen year old correspondent – when you say to her, ‘In the forest of things, that’s how we met.’ What do you mean by that?

JD

There’s some strange connection for me between myself and her story. It’s hard to explain, but it’s connected to place and landscape, it’s a connection between two human beings who obviously enjoy reading and writing. It’s connected across time, and it seemed like a nice way to encapsulate what that connection was.

BB

How did you first hear about Sylvia? Or Balfour?

JD

It was actually from your foundation’s guidebook. Phil Pullinger asked me to write a few hundred words – vignettes – for that book, and he pointed me in the direction of ...

BB

That’s Tarkine Trails ... ?

JD

… that’s the one … from your Bob Brown Foundation ...

BB

From good bookshops like this one ... ?

JD

… and he pointed me to a five-minute ABC radio interview with Nic Hagarth, a local historian, who was talking about these two gravestones in Balfour. One was Sylvia’s, the other was that of

Bill Murray, a miner … the gravestones are next to each other in the forest. Sylvia was fifteen years old and died of typhoid, and the very day before Bill Murray - a miner - shot himself. Nic had spoken about this and mentioned that Sylvia had written letters, and read a section of a poem that her father had written to the paper, expressing his grief at her death. That’s how I knew about Sylvia and Balfour, and then I did the little vignette and thought, this is really interesting so I went up there and wrote an essay which was later published in 40 South magazine.

BB

You went up to Balfour? Where’s that?

JD

Balfour? It’s six hours drive from Hobart … probably the quickest way is to head up to Devonport, cross to Smithton, head south across the Arthur River and down the Western Explorer where, along the way, you’ll come across a little rock with ‘Balfour’ spray-painted upon it, and a four-wheel-drive-only track, probably five or six kilometres off there and you get into the remains of Balfour.

BB

And what did you find when you got to Balfour? You say there’s two houses left there?

JD

There are more than two; there are two that don’t have forest on the inside as well as the outside of them.

BB

How did Balfour come to be?

JD

In the late 1800’s they found tin there. That didn’t get people too excited. But then in the early 1900’s they found copper, and that got people very excited. In the space of two or three years Balfour went from nothing to a town of about a thousand people. And it disappeared almost as quickly. There were a couple of typhoid epidemics, but perhaps more importantly the copper price crashed – I believe globally – and the whole community fell apart.

BB

We’ve got Sylvia, now what’s her surname?

JD

M'Arthur.

BB

And how did she come to end up in Balfour?

JD

Sylvia was part of a mining family. She grew up in Zeehan, her father was a machine operator. He got a job in Balfour and transferred from Zeehan.

BB

Well Zeehan was at one stage the third – and at some stage, the second – city of Tasmania. It was a big town, twenty or thirty thousand people.

JD

Sylvia’s school had a thousand students, she mentions, so it was a decent size, and she laments being away from that thriving metropolis when she moved to Balfour. Interestingly, when they moved it took two weeks to get from Zeehan to Balfour, involving a train from Zeehan to Burnie, a coach from Burnie to Stanley, a boat from Stanley which had to stop in Woolnorth for about a week due to weather and which eventually made it round to Whale’s Head which is now Temma – another nightmare – and then the horse-drawn tram-ride twenty miles into Balfour.

BB

And when she got to Balfour after leaving the city of Zeehan – with its Gaiety Theatre and hotels and huge school of a thousand – what did she find at Balfour?

JD

It’s hard to say. She does talk about the trip in from the coast and mentions the beautiful scenery. But there’s a sense that she was disappointed, it’s a small place and very isolated. There was obviously a bit of hype about a railway being built from Stanley to Balfour – which they did start, but only got halfway before Balfour disappeared – so I think she was perhaps not so happy in some ways, felt a bit of loneliness being in an isolated little place like Balfour after somewhere like Zeehan where she would have had a lot of peers. In Balfour, she couldn’t go to school – there was no point because in her words, there were no girls her age so she’d be just as lonely at school as at home with her books.

But it’s clear that she found the environment very compelling. She talks about taking the two mile walk down to the Frankland River as a regular activity, talks about the buttongrass plains when the wildflowers are out, talks about the forest and the chocolate soil; she’s obviously very engaged in the environment as well.

BB

And before we get to her letters - the core of this book - a remarkable piece of fortune’s wrapped in to the fact that her father was a photographer.

JD

That’s right. Probably another of the reasons why you were able to be proved right - that it can be a book - is the amazing photographs. Her father was obviously a keen amateur photographer and he’s taken some beautiful photos that stand the test of time. He let Sylvia send them to the paper with her regular letters. A couple of the other photos are generously provided from one of the family’s descendants, Edie McArthur. One of those is a photo that she specifically mentions in her letters when going down the cage into the mine, where she was quite frightened; a man took a photo with a flash light where they all look like ghosts. It's a photo that was passed on through the family.

BB

She’s actually in three or four of the photographs in here, isn’t she!

JD

Yes, she’s in a few. One thing I need to say, in case I forget to say it, is when Barbie Kjar was first asked to do the cover portrait, I only had one photo available at that time: the school class photo, where Sylvia is quite hard to see and has straight hair, it’s very small and not very clear. But Barbie put a big plait in her hair, down the side – which was a bit of inspiration on her part because after a little time we found a couple more photos that were much better. And sure enough, that exact side plait was in several of them.

BB

Barbie Kjar is a very accomplished artist and I might ask Barbie if you’d say a word or two about the evolution of this picture of Sylvia which is so important to the book.

BARBIE KJAR

Sure, thanks. It actually came about because Bob and Paul said they had a book by James they were thinking of making happen about a young girl named Sylvia. Okay. And they said, Sylvia was born in the 1900’s but isn’t alive any more, she died quite young, she was fifteen when she died. Right!

I always work from life. I thought, I need to get a sense of someone to bring Sylvia alive, need to draw someone from life who’s of a similar age. Paul said, I know someone.

And so I drew Billie Raffety which was great. Then I looked closer at the photographs, Sylvia was very blurry, there wasn’t much to go from except this great story. So I also did a drawing of another person – Nikeisha Avio – who has dark hair and looked a lot more like the Sylvia in the photos.

What I did was try to combine the life of Billi – because she has this great sense of liveliness about her – with what I thought was a close physical resemblance from the blurry photographs of Sylvia, and reactivate this person. And when James came to the studio to look at some of the images, he said yes, that could be a good rendition.

BB

Thank you Barbie. Barbie drew this picture of a young woman who’s fourteen years old, and we know about her through one single fact, that she wrote to a Tasmanian newspaper. Tell us how that happened.

JD

It was her character, I guess; who she was. And maybe partly due to her isolation, feeling a need to communicate with other people – and probably, specifically, other peers. The best, or perhaps the only way to do that, was to write letters to The Weekly Courier, a weekly Tasmanian paper. Beautifully, that paper – for its entire existence – devoted a whole page to letters from young folk around Tasmania. It’s actually a stunning, really fascinating page, in some ways I guess an early version of Facebook, all these young people communicating across the state back and forth to each other.

She'd write her letters, which would then be transported on a pack horse to a ship. It probably would have taken the best part of a week to get to the Weekly Courier

There’s a real sense that even though she’s addressing the letters to Dame Durden, the editor of that Young Folks Page, it’s clear – to me anyway - that she was writing to more than just Dame Durden, she was writing to other young people, probably writing to anyone else who would read it, and probably in some ways writing to herself as well.

BB

Exactly. And she mentions, repeatedly, both her love of nature and her loneliness. She was lonely when she was at home and lonely because she couldn’t go to school. Her great excitement was found in two things, in nature and in reading books. Where did she get the books from?

JD

I’m not sure, but there was obviously a steady flow coming into town because she churned through them, she lists some of them in her letters.

One other thing that’s clear is that she was obviously very maternal, there’s evidence that she always had the town’s children hanging off her and she was a natural babysitter for everyone. Clearly very well loved. There is a story in the Circular Head Chronicle that mentions when she died the street was lined with big, burly miners, all crying. She was well loved, there’s certainly no myth in making her into a special character.

BB

You talk about your own two sons and how you, in your mind’s eye, can see them playing with her two little brothers, who she talks a lot about. In fact, she writes

My brother Willie is a funny little fellow. He will be three in July, but he thinks himself quite a man. He can sing almost anything; in fact, he is famous for his singing, and all who have heard him say he is really wonderful. On a recent Sunday, about 11 o'clock, we missed Master Bill. We searched high and low but he was not to be seen. After a while I had to take my dad's 'crib' to the mine, and, to my great surprise, who should I see but Bill! When he came home he said to his mum, "My dad says not to beat me too hard this time." Of course, we all had to laugh.

It’s said in the commentary that she was never seen without a child, either one of her brothers or she’d borrow somebody else’s baby. So you’re right, she had a terrific relationship with the children of the town – in fact, with everybody. But tell us more about the structure of the book. Your book offers your writings in response to her letters to the Courier.

JD

In some ways it came about semi-naturally. I went up there the first time for the 40 South piece. There’s something about the landscape up there that’s really powerful. It’s so rugged, feels like it’s full of memory, stories and ghosts, it’s just a powerful place. And then, the layer of top of that, is you’ve got Sylvia’s letters which are really intriguing; you get to know this person. And there’s a heart-breaking end to it when you get to the letter from her parents.

BB

There was a letter too in the Launceston Courier after she died, first one from her mother then one from her father.

JD

Yes, they were combined, the mother wrote a letter and then the father wrote a poem – together – notifying the Young Folks Page that she’d passed away.

Then of course, the other layer on top of it is the incredibly powerful feelings you get in a ghost town. There’s something very strange and moving about walking around a place that you know was once a busy little town full of people and activity, families, life and stories, that is almost invisible. That’s gone basically.

You’ve got all those layers that are deeply moving within themselves. I remember that first time, finding the track to the cemetery, finding my way down to the river. It became a conversation in my head with Sylvia and the past, exploring the letters - Sylvia became a line for the feelings those layers created, she became a lens for that. It was Pete Hay – after your suggestion it become a book – who said it should be written as a dialogue. It took me a traumatic four months to convert into that kind of structure, but I’m very glad that I did.

BB

Pete Hay writes, ‘To span the baffle of time. To touch a lost life at once ordinary and extraordinary across time’s opacity. That is the challenge James Dryburgh sets himself in this sensitive, loving book. Come with James into the sad, doomed bush town of Balfour. Here you will meet Sylvia and your life will shift.’

Well your life shifted, didn’t it?

JD

It did, definitely. If feels like I knew this person as if she was a relation or ancestor…. I don’t want to get too carried away, but it felt like that because of my reading and thinking so much on the subject. It is hard to read Sylvia's letters along with the heart-breaking words from her mother and father and not feel some love for that person. It’s been quite a journey, has made me think about the relationship between the natural world and language. Sylvia offers an example of the power words leave behind. In some ways, you couldn’t pick a person with less influence, less power, less voice than a fourteen year old girl in Balfour a hundred years ago, But, here we are, we’ve a portrait of her now on the cover of a book. She’s caused me to think a lot about language and how we use it, how we have a choice as to how we use words, what words we leave behind, how language evolves.

BB

And you say, in one of your letters to Sylvia, that you’re not only the Balfour correspondent, you’re the Balfour historian, because what we know of her is largely – in living Balfour, that is – is largely here in these pages. Without Sylvia, that wouldn’t be recorded.

She obviously had a great love for her parents, even though her Mum had died, her new Mum who’d given birth to the boys was obviously very affectionate with Sylvia and that was returned in spades. I note that you’ve dedicated the book to your Mum and Dad; what influence have they had on this book?

JD

Quite a lot, they've always been extremely supportive of my writing, and were very enthusiastic about this project. They helped frantically with editing, they came up to help look after Santiago on the second trip as well.

There’s more to it than that, actually. There’s something in this book and the experience of making it that's about belonging, about family, and it’s made me think a lot about descendency, ancestry, about what carries on and what doesn’t. What passes through people, what passes through place, the things that we receive from our parents and grandparents – consciously and unconsciously. Our values, our various qualities – I know my parents have passed on to me a love of nature, compassion, a desire to have a gentle step on the planet, a big nose....

It felt very natural to dedicate this book to them.

BB

And with Sylvia, she had no real wisdom of the world. I mean, her idea of heaven might have been to spend a few hours in Fullers Bookshop, because it was books that gave her the greatest joy. And people around her. And nature.

But of course, the thing that we have to address in this talk is that at age fifteen, she dies. Typhoid swept through Balfour - for the second time in that year, it appears - because the sewage was not being properly disposed of. Sylvia’s Mum says in her plaintive letter to the Courier after the girl dies, she was brave to the end and the illness was short. But in fact, she asked for the latest copy of the Courier three days before she died, and Sylvia was too weak to read it, this bright-spirited, upbeat, optimistic young girl - the last thing she wanted to do was to read the latest copy of the Courier. We can only imagine the horror of those three days for her and for everybody involved, as a very healthy young woman went from the prime of life to death. And I’m sure that’s something you can’t help but feel a great closeness to when you’re looking at that lonely gravestone there – well, there’s two others – in what’s now the regrowing rainforest that’s taking Balfour back into the natural realm of the Tarkine.

Have you thought about those last three days? As a correspondent and somebody who knows more about this young woman now than anybody living, what's that mean to you?

JD

Yes, I have. When I eventually found all the letters and read my way through them from start to finish – it was heart-breaking. Her letters are simple, but you get such a sense of her, she’s extremely likeable. I can’t explain how six fairly short letters make you feel so fondly towards someone.... The letter from her Mum is also heart-breaking, the poem from her father equally so.

I’ve only been a parent for four years; you can’t imagine what that would feel like. It’s no comfort to her or her family but.... I wish she could know of the interest in her because I think she'd have been wrapped to think there’s a book about her. You get the sense she was the kind of person who’d have been over the moon about it, and I’m really happy she’s been honoured in this way.

BB

One of the intrigues of the universe, of course, is that we don’t know that she doesn’t.

I urge everybody to read this poem at some time, it is a remarkable poem of a father's love for his daughter. I'll read the last stanza.

And the fiercest storm in winter,

As it rages on the shore,

Will not disturb you, dearest Sylvie,

Where you sleep for evermore.

He’s gone from ‘Sylvia’ to ‘Sylvie’, and in his hope and his religious beliefs he’s trying to make the best he can of this awful tragedy, out in the remote back blocks of Tasmania over a hundred years ago.

Anything else you’d like to tell us about this production?

JD

The only other thing maybe we haven’t touched on but which continues to fascinate me is the connection between the natural world and its processes, and human memory. I think for me that connection was first made when I lost my oldest friend who died kayaking six or seven years ago. I experienced dreams and feelings drawing connections between dealing with death, and the natural world. I wrote about that at the time. But I felt strongly about Sylvia's story as well. Maybe there's something there, as simple as the need to go to a quiet and beautiful place, the way it helps get everything else out of your mind and frees it up for memory and imagination. It’s maybe that simple.

It may be more complex, maybe the natural world is effectively a bank of memory - the memory of life, in a way. The most complex beings still contain memories of the very first cell. I find that fascinating, it continues to pop up in my life. I’m not sure if anyone here has similar feelings but I think there’s something in it. If you want to have memory - including time for thought and imagination, which obviously leads to memory – there’s definitely something in going to a special, quiet place that hasn’t been too disturbed or manipulated by progress.

BB

Sylvia went and sat by Frankland River, and the very last footnote to her very last letter is that Mr Lyle had caught – I was astounded by this – a two-foot long native blackfish out of the Frankland River. I don't think you'll find a two-foot long native blackfish out of any Tasmanian river these days.

James, you’ve put so much of yourself into this book. I think that’s generous, and I think Sylvia would be incredibly honoured by the sensitivity but also the openness with which you approach responding to her letters and her life. It is in the widest sense of the word, a book of love, the love of human beings for each other. Which doesn’t have to be confined to the here and now, but can span time; books and language allow us to do that. You’ve discovered in six short letters to a Tasmanian newspaper, over a century ago now, the means to express that wider love we human beings need to have for each other, particularly for people we can’t see immediately or whom are not in our vicinity; maybe not even in our time.

And I think forward to future generations who we should maybe consider a lot more in the way we human beings interact. It’s a sad but nevertheless hauntingly beautiful story and you’ve brought to life not only a sterling young spirit of Tasmania a hundred years ago, but the little town that came and went. And at the end, it’s ennobling … it’s the book you can give and send to anybody, it can be read over a cup of coffee, the photographs in it are of themselves beautiful, if not haunting, mainly taken by her Dad. The illustration that Barbie’s provided gives us an added connection to this young spirit who you’ve brought back to life and communicated with in such a poignant fashion in 2017. So thank you James Dryburgh for The Balfour Correspondent.

BOB BROWN is an activist, author, photographer and former leader of the Australian Greens. He led the campaign to save the Franklin River in the 1980s and has served in the Tasmanian Parliament and the Senate. He retired from Parliament in 2012 to establish the Bob Brown Foundation.

JAMES DRYBURGH has been published in a number of publications including Smith Journal, New Internationalist, Wild Magazine, Island Magazine, Tasmania 40 South, amongst others. James writes provocative essays about important things. His first book is Essays from Near and Far.

BARBIE KJAR is a Tasmanian artist and has completed a Masters of Fine Art at RMIT, Melbourne; Bachelor of Fine Arts and Education, University of Tasmania, Hobart. She has undertaken residencies in Caylus, France, Rome, Barcelona, Havana, San Francisco, Mexico City and Tokyo and been the recipient of several Australia Council grants. Since 1986 she has held 36 solo exhibitions in Australia and more recently in Barcelona and Tokyo. She maintains a website presence at barbiekjar.com