RALPH WESSMAN | NORTH TO GRRADUNGA

ANNIE MARCH, 'BUTTERFLY'S CHILDREN' || GEOFF GOODFELLOW || LIBBY GOODSIR, 'IT CAN TAKE TILL NOW' || SAM GEORGE-ALLEN, 'WITCHES' || PHILOMENA VAN RIJSWIJK, 'HOUSE OF THE FLIGHT-HELPERS'

ANNIE MARCH, 'BUTTERFLY'S CHILDREN'

Some eight or ten years ago, I chanced upon a wonderful essay published

in Island magazine penned by Hobart writer, Annie March - as memorable an essay as any I'd stumbled across in recent memory.

I sought Annie out, eventually becoming

involved with the publication of her book As A March Hare (Walleah Press, 2011), wherein - incidentally - that essay's reproduced.

I should reread the book: it deserves it for the thoughtfulness Annie brings to the table,

that nuanced mix of worldly observation with the private and personal.

If it's the work of our generation to restore a planet, what's my task? How do I live my life as authentically and ethically as you live yours?

Your journey is solar, extroverted and public. My moiety, it seems, is the underworld. I live in the dark, mapping its countries, oceans

and galaxies.

As a writer of fiction, I spend hours every day creating out of nothing a landscape that doesn't exist except in my imagination,

and yet is dancing, alive and more real than real; going 'down the rabbit-hole' is as pleasurable as going to meet a lover.

(from As A March Hare).

From Annie's 'dancing, alive and more real than real' restive imagination, eight years later, has emerged her second book,

Butterfly's Children, (Panacea Books, UK, 2018, 506 pp).

Book One of the Thalassan Trilogy, Butterfly's Children is set on Planet Thalassa which

'... seven light years from Earth and four centuries

in the future – is transforming from an anthropocene to an ecozoic culture where wealth is construed as pure air, rich tilth, clear water,

a glory of biodiversity; and human violence, thanks to Redound Syndrome, which triggers perpetrator death by endocrine meltdown, is all

but extinct.

The story constellates around the young heroine, Meriel, whose flight from her own demons implodes in shipwreck on an island that doesn’t exist.

Other characters and artefacts: an intergalactic unicorn, Universal Male Contraception, splendid cats and crones, and xirilliry-hulled Light-ships

skimming the sea like dragonflies.

Butterfly’s Children is political, metaphysical, redemptive, richly imaginal. It includes an Understory (planetary guide), a dictionary and

alluring maps. It’s been 35 years gestating, and is my viaticum to all the children – albatross chicks, sapling Huon pines, tadpoles, lion

cubs – of this beloved, beleaguered Earth.'

Needless to say, I'm very much looking forward to immersing myself in Annie's latest offering....

GEOFF GOODFELLOW - HOBART, FEBRUARY 2019

It’s always good to catch up with poet Geoff Goodfellow. He’s been touring Tasmania

this week, visiting local schools and the prison, talking poetry.

‘You’re becoming a local, Geoff…. ’

‘Well I find that when I go into the schools, the year nine’s—they won’t know me—but

the year ten’s, they’ll remember me from last year, come and say hello, ask how I’m

going.’

‘Do they give any trouble?’

He laughs. ‘Nah…. I don’t let ’em.’

He says it’s easy building a rapport with the students. He’s direct and blunt, speaks in a

manner they’re not used to from someone with an authoritative role within a school

environment. And once he has their attention, his message is always the same.

‘Concentrate on your studies, don’t waste your time here—or mine—cos it’s the only

way you’ll get ahead.’

His words resonate and I ask if he’s read any Margaret Drabble.

‘Can’t say I have.’

I mention her 2000 novel The Peppered Moth, wherein Dabble’s school-teacher

character Miss Heald implores her students of the necessity of ‘deferring pleasure’.

“Work hard now, she said to her young people, and reap the rewards later. Do not grab

the instant….”

Geoff nods, says he has pretty much the same message for the students he deals with.

‘I tell them their school work’s important. That they have to set themselves a time

frame, picture where they’d like to be in ten years time. In my day it was enough to

finish matriculation but nowadays even a BA won’t guarantee you an interesting career.

You might need a Masters, even more. You might be in your mid-twenties – or later –

before you find yourself with a job you enjoy.’

..........

So what does a poet read for pleasure?

‘Poetry of course; novels too,’ Geoff replies. ‘I came across a copy of an old Carson

McCullers novel recently’—(perhaps The Heart is a Lonely Hunter?)— ‘read the first

page and decided, that’s for me so I bought it.’

He says he wouldn't do it the disservice of glancing only casually at it, but would take

the book home, sit down and give it his undivided attention.… From his reading of the

first page, the book deserved it.

Geoff's website biography describes his writing as often providing '... a public voice for

those living close to the margins and who are generally under-represented in

contemporary literature,' which perhaps explains his interest in the award of the 2018

Man Booker Prize last year, won by Anna Burns with her novel Milkman. (In an article

entitled 'The story of Anna Burns shows how working-class talent is going to waste',

Guardian journalist Suzanne Moore argues that the creative industries now belong to

the wealthy and their offspring. 'Who else can afford to be a poet, or make music the

way they want to, or make art that a big collector doesn’t want?')

‘I was listening to the morning news late last year and heard Milkman had won the

Booker overnight,' Geoff recalls. Later in the day he was on the phone to his daughter

Grace who mentioned in passing she’d gone and for the first time bought a book

online.

‘Oh, what book is that?’ Geoff enquired.

‘Milkman, by Anna Burns’, Grace replied.

‘Oh, that’s just won the Booker Prize,’ he said.

‘No it hasn’t, though it’s on the shortlist.’

‘No no no, it’s won overnight,’ Geoff insisted. ‘Listen,’ he added, ‘once you’ve finished

the book, how about letting me borrow it?’

‘Sure.’

A week passed. Geoff asked how Milkman was going.

‘Oh I haven’t started it yet, I’m reading something else at the moment.’

Another week passed. ‘How’s Milkman?’

‘Just begun.’

Another week. ''Milkman?'

‘Oh, I haven’t read very far yet....’

Yet another week. ‘How’s Milkman going?’

‘Still reading.... ’

When eventually he got his hands on the book, Geoff found it hard to settle into. ‘I read

to page 11 and thought, this is tough. I gave it another go and reached page 27 before

I put it down again, thinking, I don’t want to waste my time reading this. But I told

myself not to give up so easily and continued with it—though it wasn’t till I reached

around 150 pages that I began to pick up the rhythm and intonations of her voice….

That’s when I started to think, this is good.’

‘I’m glad I persevered!’

...............

Geoff mentions meeting Ken Kesey - author of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest - at

an Adelaide Writers Festival in the early eighties, and how that developed into

friendship and an offer to stay with Kesey in the US. ‘I was on the bill in Adelaide, so

was Ken. I sensed his interest when he heard me read and he later came up and asked

for a copy of my book. ‘I’ll give you one of my own tomorrow,’ Kesey added.

Geoff had heard of Kesey, said yeah - that’d be good. They met up the following day

and got talking. ‘When I hear others reading, they could be from anywhere. When I

hear you read, I recognise I’m listening to an Australian’, Kesey confided. He said to

look him up if ever got to the States.

Geoff says it wasn’t time for him to be heading overseas—to begin with, he didn’t have

the money—but eighteen months later circumstances had changed and he rang Kesey

to see if the offer still stood. Before long, he found himself in Kesey’s expansive

Eugene, Oregon home.

Among their many conversations about poetry and music – a Kesey quote is ‘The

Greatful Dead are our religion. This is a religion that doesn’t pay homage to the God

that all the other religions pay homage to.’ - the possibility of a Goodfellow poetry

reading in Eugene was floated.

‘Not being a local, you might find it difficult getting an audience,’ Kesey mused.

‘I’ll get by,’ Geoff insisted.

‘How?’

‘Well, I’ll visit radio stations, put posters up around the place. I’ve done this before.’

‘It might work if we did a reading together,’ Kesey mused, ‘but the thing is…. I’d only

do it on one condition, that it’s free for people to come and listen. This is my town, I

don’t want to be ripping people off. But we could take our books and sell them.’

‘And we did,’ Geoff concluded, ‘it was a great experience!’

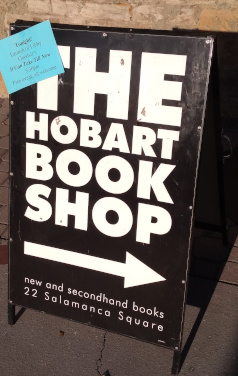

LAUNCH: LIBBY GOODSIR, 'IT CAN TAKE TILL NOW'

Hobart Bookshop, Hobart, Thursday 3rd April 2019

Just as it's been for much of her life, the creation of Libby Goodsir's new poetry title It Can Take Till Now was a joint effort.

On the one hand is Libby's poetry, on the other the handsome embellishment of her writing by husband Bruce with his natural flair for

illustration and design.

Just as it's been for much of her life, the creation of Libby Goodsir's new poetry title It Can Take Till Now was a joint effort.

On the one hand is Libby's poetry, on the other the handsome embellishment of her writing by husband Bruce with his natural flair for

illustration and design.

Perhaps it was only natural that it took another joint

effort–by Aurora Hammond

and Neeta Oakley–to launch the book.

Aurora, who'd flown from Brisbane for the event, began first.

She admitted that though she'd never launched a book before, she understood it was somewhat similar to the launch of a ship,

'done with champagne'.

What was certain in her mind was that attendees were gathered here because 'you're lovers of books, lovers of words ... and we all love Libby

and Bruce.'

'I knew Libby before she became a poet,' Aurora continued. 'A poet is a person who has the skill of using words in a particular way–and

in Libby's very concise poetry, sometimes it literally takes my breath away how much she is able to convey in just four lines. That is an extraordinary talent.

And I reflect on how I've loved listening to Libby hone that skill over the years and thinking of all that she writes about....

I would often say to

people that I feel I learnt a lot of my mothering skills at their kitchen table, being part of that family, that life. And you get a real taste of that as you read this book.

One of the things I've learnt through my professional life as a therapist is that the ability to live life well is one thing; the ability to

have insight into what allows you to live it richly is the next layer if you like, the next level. This poet's book gives us a

way of reaching that next level without necessarily having that insight ourselves; as we read the poetry. it can open

a door in our lives.

An example of that – and there are so many – is a chapter in the book entitled "There are times when you need to say thank you, over and over again."

Now that, I believe, is a real truth of the heart. In some families, there is not one person who knows how to say "thank you" to anyone in their

family. And to hear someone say that, so simply – a mother and a grandmother, a daughter, a sister – who knows that there are times when you need

to say "thank you", thank you for being in my life, thank you for being in my heart, thank you for bringing me the joy, the pain, the love that

you bring me over and over again. Because once isn't enough in a loving relationship.'

Aurora also drew attention to the couple's work together. 'Both Libby and Bruce have such a keen eye of observation. And what I enjoy

about being their

friend is when I sit with them, as I did last night, and they turn their gaze of keen observation onto my life – I feel the reflection,

insight and empathy that they bring – I feel seen. Both Libby's writing and Bruce's drawings reflect this quality of insight – with Bruce's

drawings, you see the person he's drawn but there's that little twist, that little quirk, that little figure in the

background doing something, the sprig of a leaf or blade of grass that's just saying something else, quite other. Their partnership is quite unique,

I don't know two people who do it in quite that way. This is a gem of a book. We all have our memories,

but when a poet delves into the present moment, it allows us to unpack that present moment and find something deeper and richer.'

Aurora closed with the hope people reading the book would be polished by the love within it - 'That you allow it to land in

you, rest in you and expand you into reflecting on how precious life can be' - before inviting Neeta

Oakleigh to take care of the next part of the launch proceedings.

'I have known Bruce and Libby Goodsir for 31 years,' Neeta began. 'I burst into their home when I was eleven, arm in arm with my newly found best friend, their daughter

Maddy. I loved being around the Goodsir family and their place in Lalla was practically my second home for my teenage years.

They welcomed me into their fold even though I would have considerably upped their food bill - they used to call me Garbage Guts for the

amount I consumed!'

'Over this time, I've witnessed Bruce and Libby raise their family, juggle work and dreams, have parents and dear friends die, build homes, grow

gardens, relax in their beach shack, struggle with illness and delight in the lives of their ten grandchildren.

Reading the poetry of someone you know, some one who was so essential to your formative years is an intimate experience. I felt all the more

sensitive to her tenderness, her grief, her subtle perceptions. I found myself guessing whose death she was grieving, which grandchild she was observing

and to whom the ‘velveteen lips’ she was describing belonged to!

I was delighted (& surprised) to be invited here tonight to launch Libby and Bruces’ book titled It Can Take Till Now. And I am very thankful

as it forced me to head into bed with many a cup of tea and indulge in reading a full book of poetry over a few sittings. I must admit reading poetry

can go onto the back shelf while I raise a family and work, so it was a gift to do this.

It Can Take Till Now. The very title of the book got me instantly.

It made me sit up and wonder what have they discovered this time.

It sounded wise, patient, and discerning and, I was not disappointed.

After reading It Can Take Till Now I saw the finely tuned artistry that has developed even since Libby's last book Blue Pollen Beautiful

in 2017. A honed ability to cull unnecessary words and the confidence to resist explanation. She lets her craft speak for itself.

What has remained solid in her style is the honesty and quality of words, the subtlety of observations. They stay raw and, as Libby describes in her

poem 'I Have Taken A Risk', she resists them 'becoming like polished fruit'.

This poetry collection includes the big events of life: birth, death and ageing. Mostly importantly though, it tracks the movements of

daily life - locating the momentous in the small.

The poems you will read in this collection, in terms of chronological order are a motley crew. Some were written as far back as 15 years ago

when Libby would have laughed at the concept that one day she’d be a published poet. Others are extremely recent, ones that Libby persuaded the

publisher to add right at the last minute.

The poems and images are sequenced into titled chapters that could potentially sit uneasily next to one another. There is a chapter titled

'Lizard and Berry and Wild Pear' where we read about the couple’s desert experience in Alice Springs. Further along we open

'Words To A Grandmother Called Hatti' where Libby has woven the words of her grandchildren (collected over a span of 20 years) into

a stunning ode to their natural wisdom and her appreciation of them. However what happens when the book is read in it’s totality is that

the varying chapters merge to represent a rich full life and consequently a fully rounded book comes on fire - like on the cover page that

Bruce has illustrated.

Bruce’s drawings etch visual records throughout this collection. Charcoal, pencil and ink - mediums that I strongly relate to Bruce and

the Goodsir family elevate what Libby is conveying. Some of the images feel almost whimsical, some shadowy while others are crisp and

striking in their marking. All of them are exquisite and almost intimidating in their skill.

Bruce’s deft artistic talent have always moved me, as it will you when you open this book and take in his images of Alice Spring elders,

cherished friends, buoyant grandchildren and Australian landscapes. My oldest memory of Bruce is through those eleven-year-old eyes,

seeing him hunched over paper on a table, completely absorbed in drawing a hand. It amazed me that someone could actually draw a hand

that looks like a hand and that it could be so very beautiful.

For Libby, creating this collection of poetry and images with Bruce in their late-life years has been heartening for her. Drawing and

writing she told me ‘gets them away from the realistic, the pragmatic’. They delight in the joint discovery of the abstract.

I want to deeply thank Bruce and Libby tonight for joining forces, for their dedication to creative endeavours and for making this book

happen. It Can Take Till Now is a gift to us all. And it is pure treasure for your family for generations to come.'

SAM GEORGE-ALLEN: 'WITCHES - WHAT WOMEN DO TOGETHER'

Fullers Bookshop, Hobart, Thursday 14th March 2019

A quote by essayist Joan Didion begins ‘I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the person we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not’, and Sam George-Allen does just that when she writes in her introduction to Witches that

‘This book is a letter to my former self, and to anyone who’s ever felt like her. Look at all these women, I want to say. Look what happens when we come together. Magic, some people say, is change driven by intent. Of course we are witches.’

A writer and musician based in Tasmania, George-Allen’s work has been published in journals (among them The Lifted Brow, LitHub,

Scum, Kill Your Darling, Stilts, Overland and The Suburban Review), and shortlisted for prizes including the Queensland Premier’s

Young Publishers and Writers Award. ‘Witches’ (published by Penguin, 2019) is her first book, written with sensitivity, authority and a natural spirit of enquiry on topics variously

entitled

‘Make-up: The beauty club’, ‘Sportswomen: The body is a verb’, ‘Trans women: Transitioning to girl power’, ‘Sex workers: Laws of Babylon’,

‘Nuns: A radical order’, among others.

Conversations with interviewees are interlaced with George-Allen's personal reflections—this, for example, from ‘Make-Up: The beauty club’:

‘But in terms of spaces that allow ordinary women to access a form of femininity that encourages collaboration rather than competition, digital beauty communities are unique. Once I started to talk to other women about make-up online, it opened up channels in my real life as well. Now I talk to all my friends about it. Make-up talk I coded as shallow, but it makes for deep connections. We talk about tricky aspects of beauty; we tease apart the political mess of wanting to be pretty but maybe not wanting to want to be pretty; we get theoretical.'

It's also a book addressing contentious issues. In the chapter ‘Trans women: Transitioning to girl power’, George-Allen refers to debates about gender—'its fluidity, its legal recognition, its restriction to one bathroom or another'—heating up around the world. 'Those conservative opinions—that there are only two genders, that whichever one you're assigned at birth is it, and that those who move from one to the other or who occupy the space in between are aberrations—are not backed up by science or by lived experience.’

*****

George-Allen mentions she's been a writer for about ten years, during which time she’s mostly written what she likes to call creative non-fiction, in her case

a blend of memoir and research. ‘It’s a form I use to try to tease apart the problems that bother me. My work is mostly about women and gender, so I’ve

written about beauty rituals, the body, religion and its relationship to women…. Throughout this’—here she laughs—‘I guess you can call it a career ...

throughout my writing career I have been thinking about the value of women’s relationships, women’s collaborations with one another.

That is where this book comes from.’

She says that ‘Like a lot of suburban white girls I was very into wikka when I was a teenager and in my early twenties’, and had returned to witchcraft

a few years ago ‘in a kind of tongue-in-cheek way’. Her thinking about gender and women’s spaces—and witchcraft—led to the idea of writing a book using

the terms ‘witch’ and ‘witches’ as a premise through which to explore the power of women collaborating with one another.

‘I think “witch” is particularly interesting as a term because it has connotations of suspiciousness, and inscrutability, but also the connotation of power.

It’s not like other gendered slurs that we use for women.’ The aspects of suspiciousness, of the nefariousness doings of witches were interesting because

at the time she was growing up, groups of women seem to be constructed as places of suspicion. 'People were suspicious of women in groups. Suspicious and

disdainful, there was a combination of dismissing them and being a little weirded out by them.’

This fed into something else she’d bought wholeheartedly as a young teen, which was that other women were sites of rivalry, and competition, rather than

opportunities to collaborate or work together or have rewarding relationships with. ‘And then I reread “The Beauty Myth” by Naomi Wolfe, published in 1990,

a fundamental text for me—and I started thinking about how Naomi Wolfe describes the social apparatus of the beauty myth which is designed to keep women

disempowered and unfocussed—disenfranchising themselves, distracted by conforming to mandatory standards of beauty. I started thinking about mandatory

female rivalry, and the way we are coaxed into this false economy of believing that there’s always only room for one woman on the board, or one woman in

the band, or one woman in the group of friends.’

‘I decided to write about groups of women who do things together, and everything positive that comes out of that. Just like the beauty myth, I think the myth

of female rivalry is designed to keep us apart, designed to keep us disempowered—and if we overcome that.… Well, we’re seeing it now. You see it in the

Me Too movement, you see it with Beyonce and everything she does with other women, we see the incredible power women can access when they choose to

work together.’

‘It can be hard to unlearn the things that culture presents to us, but it’s not impossible. I tried writing Witches to address this…. ‘

AUDIENCE QUESTIONS

Can you tell us some more about the women you met, the people of whom you’ve shared these stories?

‘Probably the most memorable person was Sister Maryanne. I spoke to her for the chapter I wrote on nuns, she’s a Sydney woman from the Sisters of Charity—and she was completely not what I was expecting. I had never met a nun before. I know, that’s probably unique to my generation, people older than us are

probably familiar with nuns from Catholic schools—all kinds of places—but there’s been a huge decline in the number of nuns from the 1960s and now they

feel like an endangered species. I was expecting the penguin habit, I was expecting that possibly she’d be brandishing a ruler, my main point of reference

was the Blues Brothers....

She was incredible. She wasn’t wearing a habit, she’s a professor of theology, she was so generous with her time and wisdom. She was also chilled about

the very idea of God—‘you know when I say “God”, I mean, it’s the unanswerable questions, you know, the divine mysteries—I’m calling it “God”. You

can call it whatever you want….’

And I’m thinking, ‘You’re a nun?’

Did you write about any Aboriginal people?

'I did, I co-wrote a chapter with a Brisbane indigenous elder, Aunty Dawn Daylight. She’s like this fulcrum around which the entire West End community

revolves. I lived in West End for a long time, and she is the great-aunt of some of my friends so I had this connection to her and asked if she wanted

to write a chapter with me. She talked about being taken from her family, and put to work in All Hallows Girls’ School - and coming out of this severe

childhood trauma to become someone upon whom the community really relies on. I felt so lucky to talk to her because she encapsulates how important these

particular women are to their communities.’

How’s the book changed you?

'That’s a good question. It’s changed my writing process, I don’t think I will write my next book the way I wrote this one which was mostly frantically

at two in the morning.

It definitely did what I wanted it to do. I have so much genuine respect and admiration—and I owe such a debt to—the women who I spoke with. It’s

probably changed the way I relate to other people.

It’s also done a lot for me in terms of changing my relationships intergenerationally. I spoke to women who were much older than me, and who were younger

than me. It’s very easy for me to speak to people in my immediate peer generation group, and that has just made me feel so much more connected and so

much more aware of the richness of these people’s experiences.'

This is putting you on the spot, because you’ve collected so much data no doubt from your conversations … but if you were to have a billboard and put

one thing on it from this experience, what would it be? Is there one central message or takeaway, one enlightened moment that you had…. ?

'I guess one of the main takeaways—which I didn’t expect really to deal with so much—was pleasure. The joy and the pleasure of being in those

spaces. People describe it in so many diferent ways, but it’s something about being in that only-feminine space that takes a pressure off somewhere,

a rich and unusual pleasure, of unfettered communion….

That’s too long to get on a billboard!'

You mentioned about the witchcraft. I don’t know what exactly’s involved….

'Witchcraft is very interesting. One of the things I like about witchcraft and I think one of the things that makes it so enduringly appealing to

women and young women in particular, is that it doesn’t have set parameters. So people who call themselves witches have all kinds of spiritual practices.

For some people it is a religions thing, they worship and devote themselves to certain deities. For others it is a craft thing, purely practical.

There are few common denominators….

Not everyone who practises magic is a witch, and not everyone who is a witch practises magic. Slippery terms.

But there is a kind of shared tradition of feminine knowledge which—traditionally, I guess—privileges feminine knowledge.

You can look at wikka, which people love to say traces its lineage all the way back to ancient Celtic Druids. But it doesn’t; it’s from about the 1950s.

But just because it’s not a really ancient religion doesn’t mean that you can’t take things from it that are valuable to you. I have one friend

in particular with whom I have these very witchy conversations and what we both love about it—as both atheists, not religious people at all—we love that

it privileges introspection; communion in whatever form feels right to you with nature; and ritual. Human beings love ritual, and having a part of your life

devoted to that can be so fulfilling. I think it’s exciting for a lot of women to participate in a tradition that isn't Judeo-Christian, doesn’t relate

to those very old dogmas that tend to be fairly sexist. Not always, obviously—but they can feel … not right.

Does that answer your question?'

PHILOMENA VAN RIJSWIJK: 'House of the Flight-helpers'

Fullers Bookshop, Hobart, 21st June 2019

Philomena's new novel was launched

in Hobart last month by kindred spirit and fellow writer Emily Conolan. Emily, in passing, spoke of the

book's contemporary nature. Philomena, in response, suggested it's a characterisation somewhat at odds with her initial intentions

for the book but remarked wrily she'll not be at all surprised if her portrayal of

individuals living their

lives behind city walls, sheltered under a dome, invites parallels with the cast of mind of the incumbent US President....

Philomena's new novel was launched

in Hobart last month by kindred spirit and fellow writer Emily Conolan. Emily, in passing, spoke of the

book's contemporary nature. Philomena, in response, suggested it's a characterisation somewhat at odds with her initial intentions

for the book but remarked wrily she'll not be at all surprised if her portrayal of

individuals living their

lives behind city walls, sheltered under a dome, invites parallels with the cast of mind of the incumbent US President....

'I started writing the novel in the same week that I started a job at the Huon Valley Council,' she continued. 'My desk was next to the Dog Catcher's.

The job at the Council lasted two weeks and three days. The three days were sick leave. My point is that the writing of the book

lasted quite a lot longer.

'I met a woman somewhere, around the time that I still had the caravan. She asked me where I lived, and I explained the dirt road on which we lived,

the tree stump and the quarry. She replied that she thought she had mistakenly driven up that road, once, but had been freaked out by a

woman who had emerged from a caravan and glared at her. I refrained from confessing that it must have been me.

'This book is like a core sample of my life. I guess I must have written it at some stage, but, like a pregnancy, I mostly remember beginning it

and finishing it. When I was living with two of my daughters in the Glebe, I decided I just had to finish the manuscript. I took myself off to

Saintys Creek on Bruny island for a few weeks to write the final 30,000 words. There was no TV, no internet, no phone reception, so I had no

distractions. I wrote the bulk of the 30,000 words in one day, with my heart pounding and my hands shaking. I took a photo of myself, standing

on the decking, holding up a sign saying: "One more chapter to go!" and then another when the book was finished. I looked a bit happy and a bit bereft.

'This book is like a core sample of my life. I guess I must have written it at some stage, but, like a pregnancy, I mostly remember beginning it

and finishing it. When I was living with two of my daughters in the Glebe, I decided I just had to finish the manuscript. I took myself off to

Saintys Creek on Bruny island for a few weeks to write the final 30,000 words. There was no TV, no internet, no phone reception, so I had no

distractions. I wrote the bulk of the 30,000 words in one day, with my heart pounding and my hands shaking. I took a photo of myself, standing

on the decking, holding up a sign saying: "One more chapter to go!" and then another when the book was finished. I looked a bit happy and a bit bereft.

'It's hard to say anything much about writing this book, as so much of my life is intertwined with it that it almost feels like giving your own eulogy.

I thank my family for putting up with me for all these years. Thank you, Emily, for reading the book and taking the time to think so much about it,

and thanks Clive and everyone at Fullers. I liked Emily's comment yesterday when she said that, if I hadn't been such a good writer, the book would

have done her head in. I think that's the best compliment I could have asked for....'