NICOLA BOWERY & HARRY LAING

Launch: Louise Crisp's Yuiquimbiang

Bairnsdale Regional Art Gallery

16th March 2019

Cordite Publishing

Nicola: We are going to do an unusual thing, co-launch this book as a double act. We think that Yuiquimbiang, which is quite radical in itself

in its form and content, deserves a somewhat unusual launching approach.

My first contact with Louise goes back to the time she submitted Grasses, one of the poetic sequences in the book, for a reading at the Two Fires

festival of arts and activism in Braidwood in 2007. I immediately thought ‘this work is a bit different’. And indeed I think that about all her work!

And over the years of friendship and our many hours of conversation about the writing process and about poetry, often straddling divergent views, I’ve

been struck by Louise’s extraordinary determination and yes, let’s call it, stubbornness – in a good way! And wow, she has I know needed both qualities

in the making of this collection of writings. Her powers of self-navigation in the literary context are very impressive. As also in her explorations

and recordings of country. Sustaining her in the long, mostly solitary, work of making this book. Always accentuated by being a writer in a country region.

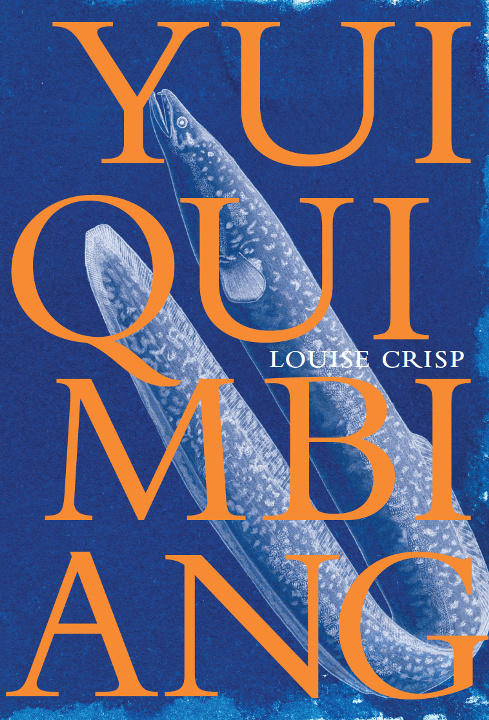

How exciting it is to hold the book in my hand, such a striking work of art, from the front cover with its wondrous eel, through all the pages, to

the back with its mayfly. All credit too to Kent MacCarter at Cordite for having the vision to, as I understand it, keep nagging Louise with ‘isn’t

it time you had another book out?’

My first contact with Louise goes back to the time she submitted Grasses, one of the poetic sequences in the book, for a reading at the Two Fires

festival of arts and activism in Braidwood in 2007. I immediately thought ‘this work is a bit different’. And indeed I think that about all her work!

And over the years of friendship and our many hours of conversation about the writing process and about poetry, often straddling divergent views, I’ve

been struck by Louise’s extraordinary determination and yes, let’s call it, stubbornness – in a good way! And wow, she has I know needed both qualities

in the making of this collection of writings. Her powers of self-navigation in the literary context are very impressive. As also in her explorations

and recordings of country. Sustaining her in the long, mostly solitary, work of making this book. Always accentuated by being a writer in a country region.

How exciting it is to hold the book in my hand, such a striking work of art, from the front cover with its wondrous eel, through all the pages, to

the back with its mayfly. All credit too to Kent MacCarter at Cordite for having the vision to, as I understand it, keep nagging Louise with ‘isn’t

it time you had another book out?’

Louise describes the book (in her introduction) as ‘part of an ongoing project to create an ecopoetic form that integrates political essay and

environmental poetics: a project that evolved out of my double life as a poet and environmental activist.’ I stand in awe of activists – their

courage and tenacity – and also admire those who know all the Latin names for plants, so Louise’s scholarship

as both an activist (researcher) and namer impresses me hugely. Luckily she doesn’t expect me to answer in the same lingo. And luckily for us as

readers this book definitely doesn’t rant at us or treat us as ignorant. It simply invites us to go walking with Louise, to notice what she is

noticing as she walks.

Harry: When I’m reading Yuiquimbiang I immediately feel I know something real about country, particular stretches of country:

the Monaro lakes,

the Snowy, East Gippsland. I become intimate with certain places, secret places, even degraded places. Whatever internal map I might have had,

my images are now overlaid and mixed up with Louise’s version. And I mean that as a huge compliment. Very few writers insert themselves into my

world that way.

But Louise, like Nicola has said, has walked up these words, walked these words into being and they do seem to come from the land itself. Such a

contrast, her own evocations, with the terse, flat and unemotional descriptions she quotes from early explorers and settlers. And one of the reasons

this charting of country has such an impact is because Louise doesn’t leave out the hard stuff, the eroded, the dry, the ripped out and the denuded.

Her eye takes it all in, charts it all. I think she’s doing something really interesting here, something unusual and daring which is to break away

from the lyric impulse that often informs writing about country and to say, look this is what we actually have now what we see now, traverse now and

we can’t know it properly until we know what’s been lost.

Here's an example from Providence Ponds

Kanangra Rd

Wind is the only thing alive in the triangular black shadows of pine forest

No wonder –

the plantations evicted more than 300 species of fauna and 700 of flora

the fallen winter pine needles lie thickly fathomed red along the rows

the early morning freezing air is held against the earth for hours

longer than in the open warming bush of hereabouts

on the road a prickly geebung turns back

its exquisite yellow petals

each flower a minuscule

resounding of the lost p 53

But I don’t want you to think it’s all depressing or that Louise deals in loss alone. She’s also a witness to abundance, to mass flowerings, great gatherings of waterbirds, kangaroo grass / truculent, succulent. And the sudden flowing of the Gungarlin River:

From Gungarlin

A deep hum rises through the canopy of trees. I have not heard that sound before. The rivers have been dry for fifty years. There is white water in the

steep valley below.

Louise and her sister Ros stumbled on this…maintenance was being done on the Burrungabuggee diversion shaft and the

Gungarlin was flowing again as a result.

And that sound seems to continue even as the river bed continues bone dry.

Nicola: Louise says: ‘The only way I know how to write is to walk.’ And that ‘…this collection is grounded in extensive

walking, listening and

research’. Louise asks us to accordingly read the book slowly; stressing she has ‘spent decades attending to this place’. Place being both East

Gippsland and the Monaro and maybe also an inner place. Louise’s rhythm of language is set at walking pace.

And with her as a guide, I’d follow Louise most places she wants to go. I do remember walking with her one time on one of the tracks near our place

bordering Monga National Park near Braidwood, a track I’m extremely familiar with. But Louise made me feel I was seeing the land there totally anew,

pointing out particular glider scrapes, prints on the ground, plants I’d not identified. It’s a bit like walking with a visual artist, their eyes are

twice as keen as one’s own. Louise also has a remarkable set of eyes, and she sees not just what is there now but what used to be there as well.

I like Louise’s clarity about her aim to integrate the political and the poetic, to write as both activist and poet. The writing, the shape of the work,

reflects this integration. I am especially touched by how successfully Louise has achieved her aim, knowing from many of our phone raves together, how

Louise had huge doubts about how to do it. How to shape this hybrid form that incorporates both prose, more in the essay style, and poetry – poetry that

is bursting out of traditional seams. How few models there are for it. How inventively, creatively she’s had to think. Outside the poetry square. Outside

the essay square. Just a couple of days ago Louise explained how she wanted to write longer pieces because they reflect the expanse of the land better

than short poems. That makes sense to me.

Undoubtedly the book provides its challenges for the reader. The pervasive lament for instance at what is lost to country and hence to us. A heartbreaking

lament, how tiny the remnants of both flora and fauna that Louise describes in places, the damage that’s been done. It’s easy to underestimate the

emotional demands of staying with the grief of what’s been lost. I can barely conceive the Indigenous perspective of that. And Louise is constantly

referring to the past indigenous inhabitation of the land, the scattered tools, the presences at a water hole.

As she describes in Monaro Lakes

A flock of sheep walks among hundreds of pebble tools anvils and quartz scrapers scattered across the lake floor p16

and

From the east I walk among manuports, tools and fragments

Whose hands, whose hands, whose hands hold the land p17

So amidst the loss there is still the chance to see beauty, to notice the exquisite detail and this is the redemptive aspect too within Louise’s vision. I recall her saying recently that beauty is vitally important to her. And she’s a poet trying to express it:

Squawking, honking, whistling, hundreds of ducks, swans, coots, grebes wheel against the high moor hill like jets coming in to land p10

and from Grasses

Further west Kosciuszko

Shoals of sparkling fish

and a five pointed-star

last snow along the skyline p29

then the poignant mix of images from Eucumbene

Sixty-year-old speckled eels

swim in the deep black water

nudging and blinking

up against the dam wall

their instinct for the Coral

Sea confounded by rock fill p38

and here’s my last quote from the end of the book, in Wild Succession,

red correa in a tangle of yellow spike wattle

strikes a match against the bitter cold p80

I know Louise says in the book ‘Yearning was not a useful thing to encourage…’ but I’ll take that flare of the match as some flare of hope that we

can learn from Louise’s fierce and loving attention to the land, and work and walk to restore its wholeness.

Harry: From that wide vista I’d like to circle back to the nitty-gritty, the nuts and bolts, sorrows and occasional joys of being an activist. As

many of you would know, Louise has been doing this looking and walking and writing of what has become Yuiquimbiang whilst also being deeply involved

in activist activities. The Snowy River, the gas plant, the forests, the Stockman mine, back to the forests. Back to the rivers. It never ends. And

it can get so toxic. It can overwhelm. But Louise doesn’t let this distract her, I think maybe she is able to tap into the power of the land or the

land taps her and she recharges again. And one of the ways she anchors herself in country and in these times is by saying this is what’s here, keep

looking, here’s a list of things. Louise enjoys a list as much as the next person –these lists of places from Grasses

Bombala, Bibbenluke, Ando, Jincumbilly, McLaughlin River, Dalgety…

Coonghoonbulla, Margalong, Foxhill, Tamanical… pp29,30

and flowers from Wild Succession

creamy candles

early nancies

milkmaids

twining fringe-lilies

tiger orchids

bulbine lilies

button everlasting

billy buttons

scaly buttons… p 83

You can hear the delight in the actual sounds and in the talismanic quality of names. And here’s another quote, again from Grasses which contains the sorrow, the concrete fact, lyric impulse and challenge to the reader :

Coming out of the ground

other side of the ford

two wedge-tails spiral

into blue air

Floating on water

wavy marshwort

rejuvenating sun

sorrow comes undone

Late summer

golden moon

looks to rise

over privatised Snowy

Breathe the intense scent

of mountain Prostanthera

and know

the contest continues p 35

Oh it does, it does.

Yuiquimbiang charts this so powerfully, breathes life into the full gamut of the contest. I declare this book launched.

Nicola Bowery is the author of four collections of poems,

most recently child in the wings (Walleah Press, 2019). She lives in Braidwood, NSW.

Harry Laing is a poet, children’s author, creative writing teacher and comic performer with a passion for poetry, comic performance

and for teaching. He has a website presence at harrylaing.com.au