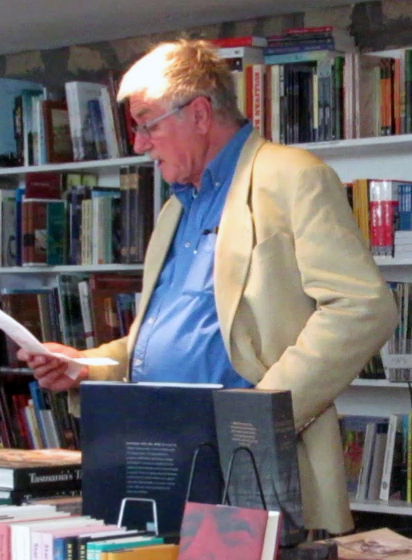

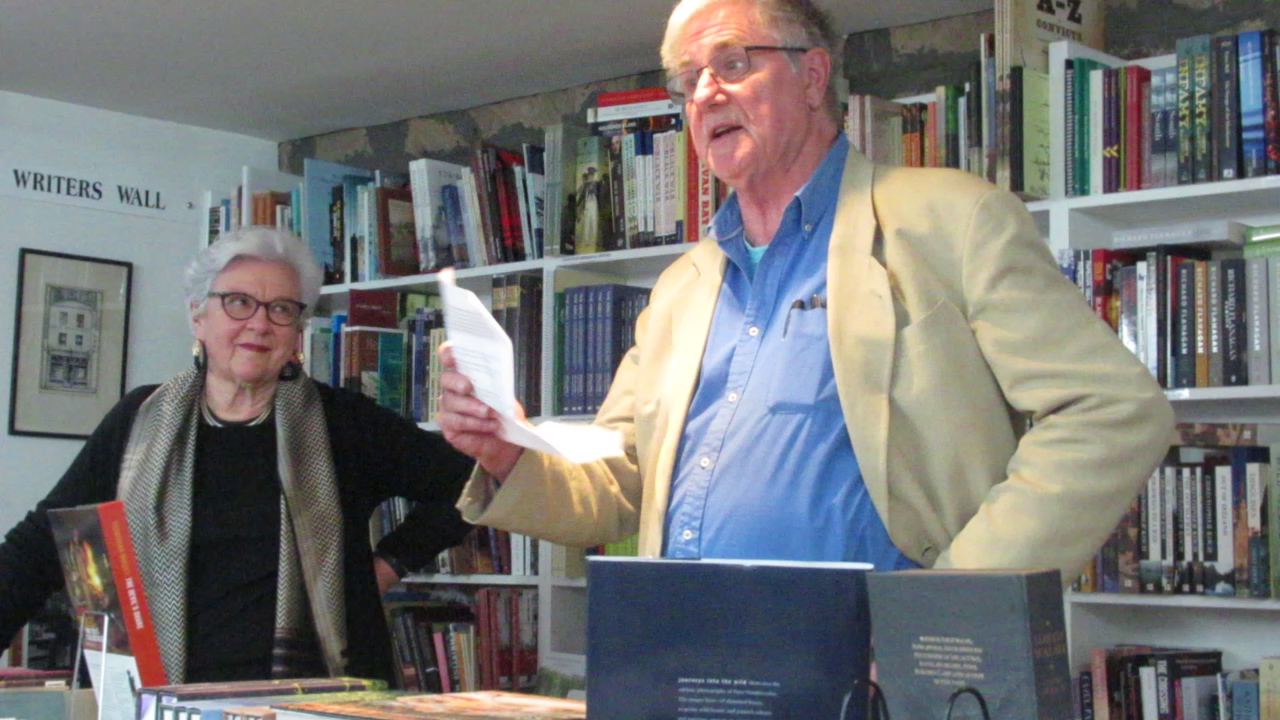

DONALD KNOWLER

Launch: Ann Page’s diary, Among the Willows and Wild Things, edited by her daughter, Margaretta Pos. (Hobart Bookshop, Friday 21st September, 2018)

Putting out the washing this morning I heard striated pardalotes calling in the garden, and I thought not of the arrival, finally, of these migrants, and spring, but of Ann Page and her diary, Among the Willows and Wild Things. She called the little birds “wetyous” because of their song, which really does sound like they are singing “wetyou”, or “pick-it-up”, and I suddenly realised that I, along with other nature lovers, I have a connection, a magic link with Ann that transcends the ages.

Putting out the washing this morning I heard striated pardalotes calling in the garden, and I thought not of the arrival, finally, of these migrants, and spring, but of Ann Page and her diary, Among the Willows and Wild Things. She called the little birds “wetyous” because of their song, which really does sound like they are singing “wetyou”, or “pick-it-up”, and I suddenly realised that I, along with other nature lovers, I have a connection, a magic link with Ann that transcends the ages.

Tonight we celebrate an often overlooked genre in literature, the art of the wildlife diarist.

The wildlife diary, usually published in newspaper and magazines, reached its zenith around the time that Ann Page was setting out to write hers. Such diaries have their roots in the ramblings, and the observations of erudite nature lovers in the 18th century, the most famous being the Reverend Gilbert White whose seminal The Natural History of Selbourne was more than a wildlife dairy, setting out his correspondence about natural history with a friend. It is considered to be the first popular book about wildlife.

This idea of a regular eye on the natural world was soon taken up by the burgeoning newspapers of the 19th century. No newspaper was complete without its natural history writer and indeed the great satire on the Fleet Street of the 1930s, Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop has a wildlife writer at his heart, William Boot, an expert on the mating habits of badgers mistakenly sent to cover a war in Africa.

By coincidence Ann Page mentions badgers, too, but uses the old term for a wombat. And her tragic account of a wombat hunt maintains the tradition of the greatest diarists and diaries - they did not shy from the harsh realities of nature and country life. The book gives us a picture of the Fingal Valley in the 1930s, warts and all.

Ann set out to explore the “beautiful unknown” of the Fingal Valley and eighty years on her daughter, Margaretta Pos, gives us the chance to join her on her adventures. Ann had a nature diary in mind but what she produced was a stunning portrait of the valley, in all its beauty, in all its seasons; in all its hardship. Wind and rain, and drought and depression. All those years ago, Ann could not have known that her extensive writings would not only record the wildlife of time and place, but become a vital social history of life in rural Tasmania between the two great wars.

The diary had its genesis in contributions she made to Little Folks; The Boys’ and Girls’ Magazine, published in London from 1871 to 1933, and over time it evolved to become a true life “Girl’s Own” adventure tale befitting a child of empire. Ann rides her trusty and sturdy steed Valiant across paddock and moor, through forest and mountain glen, across shallow streams feeding rivers “slipping silently” towards the ocean. All the while the “brooding” Ben Lomond, its ramparts sometimes in purple, sometimes in pink hues, watches over her progress.

The diary is illustrated by Sabina Gillett and edited by Margaretta, who applies a soft touch, just clarifying specific names of birds, animals and plants that might not be clear. References to badgers, for instance, have wombat in parenthesis.

Ann’s words retain a sense of wonder at what she saw around her. Moved by the beauty of a foggy day, she writes:

“A heavy fog hung over us until after 10, then it suddenly rolled back in great white banks, leaving a brilliant world behind.” At the same time life in the country could be brutal. Ann does not hide its realities, as I have said. She writes of trappers digging out the “badger” from an earth “pungent and damp with fern roots”.

“At last they caught him and, before we could say a word, killed him. I have never seen a sweeter animal, broad, fat and thick set, with a smiling, honest, kind little face, and he was flung back, dead, into his own little home. It was very sad.”

Ann also notes the impact of land-clearing on the local forests in the Fingal Valley. The site of such destruction a “rather desolate place with a sprinkling of stark, ring-barked trees and blackened stumps…”

Ann’s diaries are based on her excursions from the rural property she grew up on, Frodsley, on the Break of Day River between Fingal and St Mary’s. Although mostly home schooled, she went away to school in Hobart at one point and so was in a position to compare city life in her diary with that of the country: “The smell of gums in the heat, of soil and grass in the wet, of horse, of wild flowers and – in town – petrol!”

Ann is also aware of the economic realities of life in the country in the 1930s. She devotes an entry to the forced sale of a property owned by farmer Billy Norcutt: “Cook [a shepherd from Frodsley, with whom she often went riding] has ridden out over the hills to Billy’s little, sequestered farm to help him put his things in order. It must be sad for the poor old man, who has lived there for so long, to have to leave his sheep and cows, his many ponies and flocks of goats, his pigs and poultry, and all his other belongings. Tonight will be his last at his home. Tomorrow, strangers will overrun his home and wrangle over the price of all his old animal friends.”

Ann mentions the shepherd Cook and it is clear that he had a big influence on Ann, teaching her the names of birds, and plants. There were also lessons in the lives of the people who went before the European settlement of the Fingal Valley, the Aborigines.

On June 26 1933, on what she describes as a fearfully cold day, with Ben Lomond looming white, she says that Cook found what he called native bread. He showed it to her and she writes in her diary: “Such queer stuff, like raw crumpets, very course and flabby. The Aborigines used to eat it; it grows underground and is a sort of fungus. Its existence was proclaimed to the Aborigines by a little clump of toadstools growing above it.”

There’s something for everyone in this book, for those seeking Tasmanian history in general to those with a specific interest in wildlife.

But, reading between the lines, it throws up an interesting contrast between the way Ann was allowed to explore the world and the protective cloak we throw around children and teenagers today. Clearly the world of 1930s Tasmania was an innocent age and I’m sure today, speaking as a parent, people would be wary about allowing children to roam far and wide, rowing, horse-riding and climbing hill and mountain. For some of her more adventurous exploits, however, Ann clearly had Cook as her guardian.

Because I have a passion for birds and have written about them for years I, of course, find her descriptions of our feathered friends enchanting. And I love the way the old names for birds common in the country in those days – and still used today in rural areas – proliferate the text. Grey fantails are cranky fans and black-faced cuckoo-shrikes, summerbirds because they always arrive in spring like the swallows. Striated pardalotes are “wetyous”, as I have said, and whistlers “thickheads”.

And how’s this for a description of birdsong:

“The song of the birds was deafening. Standing still and listening, you could hear an unbroken murmur of soft trills and coos, clear chirps and crystal whistles, and the thousands of soft little notes of the thousands of little bush birds. And above the murmur could be heard the liquid song of larger birds and the refreshing, if harsh notes, of husky throated wattlebirds, or black jays. The whole effect rather resembled a faint but perfect orchestra accompanying great singers.”

Ann clearly had the making of a naturalist, or an author, or both and it is a great pity she did not continue with her writing in the style of the diaries.

She clearly had ambitions to write. She said at one point:

“When I write books I am always going to put this on the front page. ‘To my sweet Mummie. I lovingly dedicate this book.’

I hope there will be many of them.”

We have Ann’s diaries, though, and for that we should be grateful. She described the Fingal Valley as the most beautiful place on earth and clearly was inspired to put pen to paper to describe it, to share her experiences and to have a lasting memory in the written records of her childhood. As she wrote, “The spring is so pretty and soft and delicate, I wish I could do it justice in writing it down, so that I could recognise these little pictures of life.”

The diary not only gave Ann memories to treasure, Margaretta’s determination to bring them to public attention gives us a portal to a world that has vanished.